Show me the money!

Exhibiting my past performance and current portfolio holdings, expect one quarterly update!

For anyone writing about stocks, having a track record is essential. While past performance doesn’t guarantee future returns, it provides valuable context—especially for a blog focused on investing. If my insights had not led to positive results, there’d be little reason to follow them.

Fortunately, my returns over the past three years have been strong enough to indicate more than just luck (Howard Marks suggests five years as a solid benchmark for evaluating an investor’s ability). That’s why this article will be the first of a quarterly series in which I will share the current and past holdings of my personal accounts, a brief thesis on each position, and the portfolio’s returns.

By sharing these insights, I aim to build trust with readers, in the sense that I put my money where my mouth is and that my returns so far have been good, while also inviting feedback and offering investment ideas.

Below, I break down the sources of these returns and link them to the original analyses, where they are available. For current holdings, you'll find detailed explanations in the “Current Positions” section. Unless otherwise noted, the figures and positions reflect data as of September 30th, 2024.

Why now?

Last week, after nine months of consistent writing, Quipus Capital reached 400 subscribers and followers. First, I want to thank everyone for reading and sharing my work. Coincidentally, I also hit a milestone of publishing 400 articles in Seeking Alpha, following nearly four years of writing on the platform (with a year gap working for a hedge fund).

As Quipus Capital continues to grow, building trust with you is increasingly important. Trust is the greasing oil of the investment world, and the best way to earn it is by continuously providing you with high-quality content that respects the value of your time and attention.

Also important is proving (to the extent screenshots can) that I put my money where my mouth is and that some/most of the decisions I have made so far have been good regarding returns and risk.

For new readers

If this is your first time here, welcome! Quipus Capital is an ‘investment knowledge repository,’ or a compendium of ideally evergreen research on various industries and companies. I have covered seven industries across the US and Latin America, along with country analysis and reflections on investment philosophy and economic thinking. I recommend you visit the Index for a categorized list of articles.

Accounts, size, and investable universe

I have two personal accounts, one in the US and one in Argentina, where I live. They have been open for about three years each. They are approximately the same size and should not generate market impact except on very illiquid holdings.

The US account has access to the regular investment universe of US, European, and some EM stock exchanges, plus what is accessible via receipts and secondary securities in these markets. The Argentinian account, in contrast, is far more limited, with access restricted to fewer than 300 international stocks (you can visit the list here). Most of the international stocks on the Argentinian exchange are large and mega caps, an area where I have not researched much.

My general framework

My most successful positions have primarily generated returns through a combination of earnings improvement and multiple repricing, generally in cyclical industries. This approach has also proven effective across other asset classes, including bonds and ETFs.

While these may not be the most attractive businesses, industries, or countries per se, they can still generate a reliable income with some degree of certainty over an economic cycle. I typically invest in these companies when the average yield over the cycle is enough for me to feel content, even if the stock never reprices. I sell the position when and if the stock reprices to a lower cycle-average yield, which is usually coupled with earnings improvement. I have always controlled for survival factors, such as low leverage or positive earnings during the downward portion of the cycle. Otherwise, I can't hold until the thesis plays out.

That means that so far my investment framework aligns with Michael Burry’s ‘roadkill to not so bad’ thesis. I focus on purchasing (generally cyclical) businesses when multiples on average earnings are low (even if the stock currently trades at a high current earnings multiple). I sell them when conditions improve.

I have seen strong results when the cycle-average yield is very high (or conversely, the multiple very low), and not so much when the stock is close to fair value. I also don’t have much experience with compounders, quality names, and the like, but I hope to improve in this area moving forward.

Past positions and returns

US account

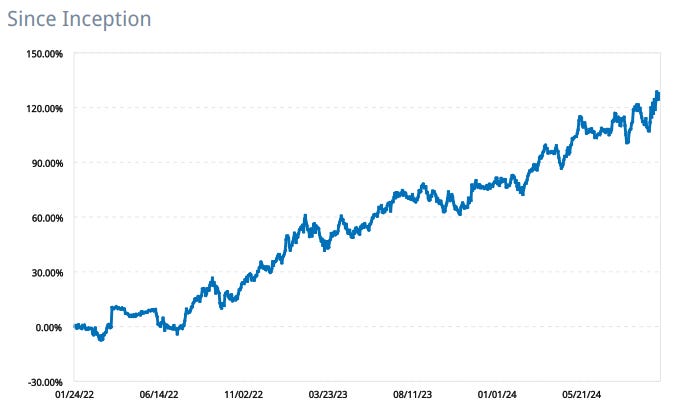

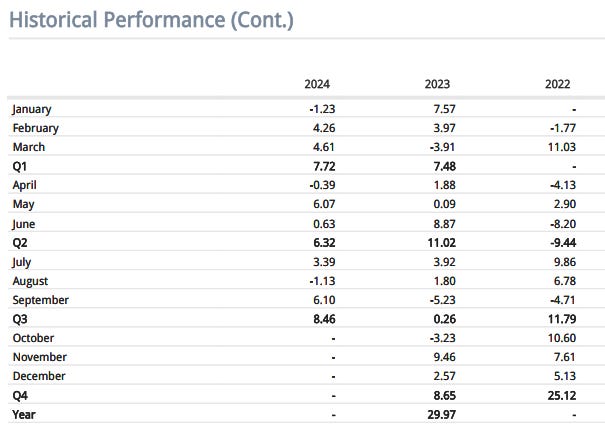

The US account has returned 125%, or a CAGR of about 34%, on a time-weighted basis over its 2.75-year existence. The money-weighted return was 110%.

Some other interesting figures are a turnover of 220%, a Sharpe ratio of 1.76, a Sortino ratio of 4.4, a max drawdown of 9.4%, and a peak-to-valley length of 1 quarter. The account has only once posted a negative quarter.

What have been the sources of those returns?

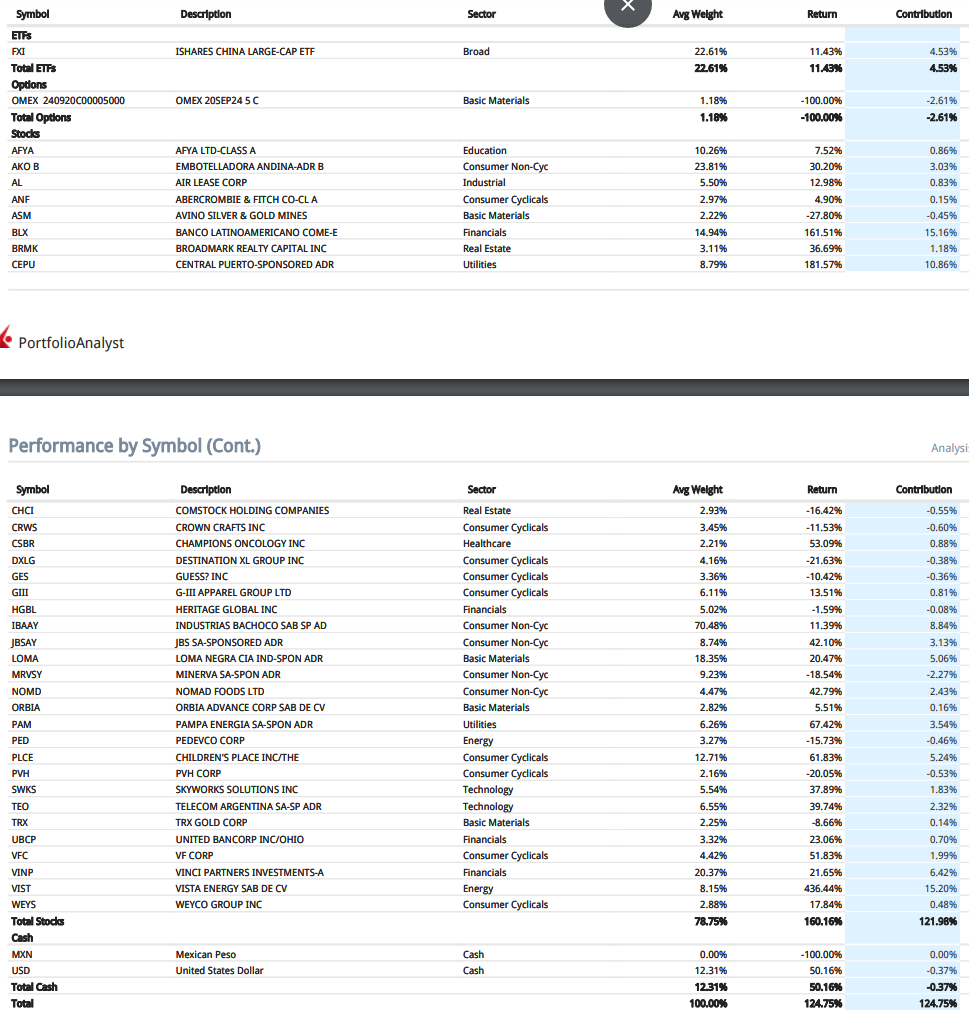

Argentina: Argentinian stocks, particularly in energy, have contributed 37% out of the 125% above. In particular, Vista Energy (VIST), with 15.2%, and Central Puerto (CEPU), with 10.9%, are two of the five largest contributors to return in the portfolio’s history. I started writing positively about Vista in October 2021, and on Cepu in April 2021. I also recommended more tactically Loma Negra (LOMA, June 2022), and Pampa Energia (PAM, March 2023).

Back then, Argentina was considered a communist country in the making, the next Venezuela. The stocks were trading at low multiples of historically low earnings. The thesis was that if the situation improved even moderately, the yield on these names would be very good. These positions were all encompassed in the Burry framework. I was not enamored of the companies’ businesses or management; I simply believed that the market was overly pessimistic. Vista is the only company in which I have more long-term confidence in its management.

By March 2024, after the election of Javier Milei, I flipped to neutral, and I have had no Argentinian exposure since. The situation was opposite to that of 2021, with much more extended multiples and expectations of a rossy libertarian future. I have reasons to believe that Milei will not be considered the next Lee Kwan Yew or Deng Xiao Ping (you can visit my article on Milei’s economic policies here).

Bladex (BLX): Another important contributor has been Bladex (BLX), which contributed 15.2%. Bladex is a foreign trade bank with conservative lending practices and quality depositors. It has grown a lot thanks to the commodity boom in Latin America. More details on current positions.

Brazil: Brazil is one of my focuses, and I have had four prominent positions in my US account. One is Vinci Partners (VINP, 6.4% contribution to the portfolio), a private equity manager from the country. The other group comprises the Brazilian meatpackers JBS (JBSAY, 3.3% contribution) and Minerva (MRVSY, -2.27% detriment). Finally, Afya (AFYA, 0.8% contribution). These are current positions that I discuss in more detail below. Today, Brazil represents 36% of my US account, and 23% of my Argentinian account (adjusting for Brazil’s weight in EEM).

FXI, a lucky mistake: I have not avoided the China battleground. I held an FXI position representing about 22% of my US portfolio, at an average of $24 (half of it was bought at $28ish in mid-2023, and the other half was bought at $20 in the January 2024 dip). I sold after the stimulus announcements at around $29. I entered the position believing it was a good place to park the money while looking for exciting positions, given that I thought the ETF was already trading at low multiples and historically low prices. Although I felt a little bad about not holding to the $35 level seen last week, I was overall happy that destiny had spared me a major loss. FXI ended well, but it was a mistake and a stupid decision. I don’t think I will ever again enter speculative, country-level, macro-level positions again. Given that I did not analyze the component stocks in detail, I have no framework to evaluate if something is fairly valued in such a case. What is the fair multiple for an ETF? Nobody knows. It was probably cheap at 8x, but is it not expensive at 12x or 15x? I can’t answer that.

Others: Industrious Bachoco (taken private, 8.8% contribution), a Mexican poultry producer, Children’s Place (PLCE, 5.2% contribution, current position), a US children apparel retailer, and Embotelladora Andina (AKO, 3% contribution), a Chilean Coca-Cola bottler, have also added their fair shares.

Petty winners and losers: I have not had big losses. This alone probably explains half of the returns. As Warren Buffett would say, ‘The first rule is not to lose money.’ Still, I have had many small losses in positions that seem either not very well calculated or outright stupid after the fact. The general read on these losses, and similarly in lots of small bets that paid off, is that I entered into small positions with little conviction. A small deviation from what I consider a fair multiple, some uninformed read on marginal business improvement, or not knowing the industry well enough to understand earnings dynamics. This framework does not work, and I have criticized it previously in one of my investment philosophy articles (here). It is better to have concentrated bets.

The complete list (the report is based on October 4th prices)

Argentinian account

Lower quality data: I have not been able to obtain as much data on the Argentinian account, mainly because balances are expressed in Argentinian pesos (a hyperinflationary currency) and because the reporting features of the broker are much less developed than for the US account. I had to manually translate the figures to USD at the time (using the MEP FX rate) and to calculate the money-weighted rate of return (basically the IRR that makes USD-denominated deposits equal the extractions plus the current balance in the account). This means I can only be happy with some rough figures for the whole portfolio and no figures for individual positions.

Good returns on Argentinian bonds: If my numbers are correct, this account has generated a money-weighted IRR of 40%. A single position carried the bulk of the work, and that is Argentinian government bonds. For two years, I was almost 100% allocated to these securities. I have not made calculations, but I think my average buying price for these bonds (between late 2021 and mid 2022) was between $20 and $25, and I sold them above or near $50 in December 2023. The thesis on the bonds was also a Burry-type thesis: the Argentinian bonds traded at 20 cents on the dollar, and even assuming another restructuring, they could potentially pay 50 cents on the principal. In addition, since 2023, they started paying high interest (a 7% coupon on a 25-cent bond is a 28% yield). This was clearly way more speculative than plays on operating cyclical companies, but it ended up well.

Since I sold my Argentinian bond positions, my account has been concentrated on EEM, Lojas Renner (LRENY), and Banco Santander Brasil (BSBR).

Current positions

US

Cash (24% of account): Cash is my largest position as of 3Q24, at a level that is twice as much as the average (12%) and the highest in its history. There are two reasons for this: I am trying to have fewer small positions, which means I need more conviction in most trades, and I am not finding the conviction to increase the trades I currently own, for reasons explained below.

The large cash position also explains why I hold a lot of EEM in Argentina (where holding cash positions is risky from a fiduciary perspective) and previously held FXI in the US account. These are supposed to be parking positions. This means I have not found too many heavy-conviction ideas in almost a year.

Childrens Place (PLCE, 12.9% of account, $9.27 cost basis)

This apparel retailer was almost bankrupt early in 2024, but a Saudi value fund quickly bought control and injected capital in low-yielding or interest free loans.

The previous management had driven the business to the ground via stupid discounting, and offering free shipping on any order size (meaning you could receive free shipping on a $3 baby shirt, discounted 50%). I published a thesis on how PLCE could solve its problems after the Mithaq acquisition (March 2024), basically arguing that the company would do better by making less revenue at higher margins.

Last quarter, management showed that it had followed that playbook, posting very good gross margins and potentially putting the company en route to generate $50 million in recurring net income in the next twelve months. After the earnings release, the stock doubled from $4 to $9, at which point I opened a position (the market cap was still $115 million). The stock continued to rally to $18 but still trades at a low multiple of what the business could generate simply by not giving away its products to create fake revenue growth.

Vinci Partners (VINP, 11.8% of account, $9.01 cost basis)

Vinci is a Brazilian alternative asset manager (private equity, infrastructure, credit, etc.). The thesis for Vinci is that it is trading at an ok yield (about 7% of market cap ex net financial assets) but that its earnings capacity can improve a lot if the Brazilian securities markets recover. I started writing positively about Vinci in June 2022. My latest piece on them is from August 2024.

The company is very levered to Brazilian assets because it can earn from performance fees, management fees on higher AUM, and the mark to model of its holdings in its funds (currently marked at about BRL 2 billion ~ $360 million). The company has received a preferred share investment from Ares Capital. It is in the process of merging with Compass, a Chilean manager of more traditional assets (mainly pension funds and Latin American HNWI investing abroad). The merger should be finished by the end of this year.

There are three risks for Vinci. First, its main funds enter redemption period before the company can extract better valuations on the underlying businesses. Relatedly, the company cannot renovate those funds (although recent fundraising activity has been good given the context). Second, the mark-to-model of its funds is too high, and therefore, its balance sheet is bloated. Finally, the merger with Compass leads to a lower margin, less interesting business.

Bladex (BLX, 10.25% of account, $14.7 cost basis)

The Latin American Bank of Foreign Trade (shortened Bladex in Spanish) is a Panamanian bank created in the 1970s to hold deposits from Latin American Central Banks (who also hold a big stake in the company’s shares). Because of this depository base (today expanded to other government entities and some corporates) and because Panama has no last resort lender (although BLX has access to the FED discount window), the bank has had a generally conservative approach to lending. The company presented no losses during COVID, and most of the provisions taken during GFC were later reversed. Most of the loans are simply foreign trade guarantees and letters of credit for imports and exports. These are naturally short-term, low-risk instruments. Despite this, and in line with generally profitable Latin American banks, the bank can extract a good net interest margin and has a nice return on equity.

The risk for this position is that both demands for credit and spreads are predicated on Latin American growth (which, in turn, implies high commodity prices). Although BLX trades at a good yield, even considering the worse historical comparisons (the Latin American lost a decade between 2012 and the pandemic), its price would probably go down on lower earnings from lower lending activity.

I started writing about BLX in October 2021; my latest piece is from July 2024.

Afya (AFYA, 9.45% of account, $15.75 cost basis)

Afya owns several private medical schools in Brazil, most of which have been acquired at interesting multiples in a roll-up play. The company’s market economics are interesting in the mid-term (more challenged in the long-term) and trades at a low yield of earnings, considering the growth it has been posting via inorganic, organic, and tuition price expansion.

In my Primer on Brazilian Education, I made a description of the medical school market. It is considered the creme of the Brazilian education market, mainly because of very good economics, with high tuition prices, an aspirational component (doctors make 3x the average professional’s salary and have low unemployment), and operational leverage. The market has a long-term challenge in the form of significant doctor overcapacity (Brazil will be saturated with doctors at this rate in a decade), but I think the company still has a long way to go before those dynamics become a headwind.

I started writing about the company in December 2021 (neutral) but only turned bullish in March 2024. My latest writing is from August 2024.

JBS (JBSAY, 8% of account, $8.82 cost basis)

JBS is one of the largest food companies in the world in terms of revenue. It has a strong position in Brazilian and US meatpacking for domestic demand and exports in cattle, poultry, and swine. It is also the majority shareholder of Pilgrim’s Pride and has a strong processed meat products operation in Brazil and the Gulf countries.

Although the market is commoditized, and there are similar competitors (like BRF), JBS has built a position based on cost and efficiency leadership. The company is still managed by the founding family and its founding managers. If the Batista family was American, it would be on the capitalist pantheon for sure, going from one butcher shop to a global empire in the span of one generation. The company has mastered the meat cycle, investing heavily when competitors are cash-strapped (in part helped by a strong and questioned relationship with Brazilian state banks, like BNDES).

The thesis on JBS was a classical Burry type. In a relatively rare turn of events, all of the company’s cycles (in the different proteins and markets) aligned downwards, leading to record low EBITDA figures. The stock collapsed and traded at a low multiple (<7x) of average earnings. Financing was not a risk, with most debt at fixed rates and with long maturities. JBS enjoys investment-grade ratings. Today, most of the company’s markets are back on the cycle (and probably peaking in the case of poultry and swine). However, I retain the name because it continues to trade at an ok multiple of average earnings, and the North American cattle business (the company’s main profitability engine) has not yet recovered.

I wrote about the Brazilian meatpackers and JBS in my Latam’s Food Products Bird’s Eye View, and also in Seeking Alpha since January 2024, with my latest from last September.

Minerva (MRVSY, 6.9% of account, $6.01 cost basis)

Minerva is one of JBS’ smaller sisters, another of the Brazilian meatpackers. The company’s business is a little worse than JBS’ for two reasons: it is concentrated on the cattle export market instead of several proteins on several markets (and therefore has more violent cycles), and it is more leveraged. However, the company maintains some of the good characteristics of JBS: still controlled by the founding family (meaning the company did not blow up previously and had to be sold), allocating capital countercyclically profiting from over-leveraged competitors (it recently bought Marfrig’s cattle operations) and building some supply-side market power, by becoming one of the if not the only buyer in some regions, like Uruguay, Paraguay, Colombia, and parts of Brazil. Today, the stock trades at low multiples of average earnings because of the challenging cattle cycle and because the company seems overleveraged based on debt taken to acquire Marfrig’s operations (the debt was recorded, but the operations have not been consolidated, meaning the EBITDA leverage ratios went up).

One of my earliest posts on Quipus Capital was a deep dive on Minerva, from December 2023.

G-III Apparel Group (GIII, 6.3% of account, $26.5 cost basis)

G-III fell like a rock in late 2022, when PVH announced that it was going to reclaim its licenses from the company (mainly for Calvin Klein outerwear), which made up 50% of revenue.

My bullish thesis on G-III is that if you discount the value of the licenses for the remaining two years of operations (until year-end 2025 for the most important ones) and assume a conservative operating margin for the remaining businesses (the company owns brands in the aspirational space like Karl Lagerfeld, Donna Karan, and DKNY, but does not disclose margins), then the stock was trading at a high yield of post-license operations.

I like G-III’s management. It has shown that it can manage wholesale relations very well (both by growing PVH’s business and its own brands). So far, its brands are growing very well, and the company is confirming that the margins of the owned brands are good.

I started writing about G-III in March 2024, including in my US Apparel Review. The latest is from September 2024.

Abercrombie and Fitch (ANF, 2.9% of account, $139.5 cost basis)

Abercrombie is probably one of my first growth positions, and I bought it recently after the drop in earnings following the 2Q24 earnings release. The company has staged an impressive recovery that has been long in the making, so this is not a roadkill idea.

My thesis on Abercrombie is that the company moved categories from a fashion manufacturer (with heavy branding, styling, and fashion risk) to a fashion retailer (low branding, trend following and focus on operational efficiencies). Although, as explained in my Apparel series (Retailers Primer and Manufacturers Primer), manufacturers are generally better businesses in terms of margin and durability, retailers can be very good if they are managed correctly. Most importantly, retailers suffer from lower fashion risk and are less volatile.

I think Abercrombie found a successful fast fashion retailing model, and most of its recent improvement has come only from higher store productivity. Although that lever has probably been tapered already, the company still has an open window for store expansion. After the dip, Abercrombie was trading at a P/E of 13x NTM earnings, which I considered fair given the opportunities for growth ahead.

I first wrote about Abercrombie on May 2024 and considered it a Buy in August 2024. I also covered the name as part of the Apparel series (Apparel US review).

Weyco Group (WEYS, 2.83% of account, $28.66 cost basis)

Weyco is a footwear manufacturer, owner of three men formal shoe brands (Florsheim, Stacy Adams and Nunn Bush) in addition to a neoprene boot brand (Bogs). Formal shoes have been in secular decline for decades, eaten by casualwear. The company’s brands are in the lower levels of price and quality. Bogs is not a leading brand either. This means the business overall is not very desirable, and I put Weyco on the value category in my US Footwear Primer.

However, the thesis on Weyco was excessive pessimism. The company is shrinking (continued since the end of the boom in 2022) and traded at a multiple of 10x on pre-COVID average earnings but only 6.5x of TTM earnings. These TTM earnings cannot positively be considered part of a positive cycle, given that Weyco was hit by the retailer destocking cycle in 2023 and 2024. The market expects a return to pre-COVID conditions, even though the company is showing positive inflection, while retailers continue to work through elevated inventories. In my opinion this implies the current level of earnings is not only more durable than expected, but also potentially an underestimation of future returns.

I first wrote about Weyco in July 2024.

PVH Corp (PVH, 1.95%of account, $122 cost basis)

PVH is the owner of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger. The thesis on the company was a Burry type: a mix of cyclically lower sales (driven by more challenged consumers) coupled with decisions to cut on some channels (licensing to G-III above, and online selling), with the stock offering a normal (10x) multiple of FY24 guidance (or a low cycle point). The thesis would play out when and if the brands recovered growth, leading to a higher multiple probably as well. I like the way management continues investing on top-of-funnel intangibles and has mostly avoided discounting (in fact cutting on lower value channels).

I first wrote about PVH in June 2024, with an update in September 2024. I also covered the name in the Apparel US Review.

Orbia (ORBIA.MX, 2.8% of account, MXN 19.75 cost basis)

Orbia is a Mexican multinational with an integrated position in the PVC markets. The company’s businesses span raw materials (an ethylene JV with Occidental, and caustic sodas) into middle inputs (vynils and resins) and final products (infrastructure, irrigation, and telco piping). Its position in these markets is strong (it claims to be largest producer of specialty PVC, #6 in resins, and largest market share in irrigation), although these markets are commoditized to a large extent. The company also has a strong position in the fluorite market (18% of global mined fluorite, largest producer outside of China, 75% of western medical propellants are manufactured by Orbia).

Because of excess capacity in China and a reduction in investment (housing, irrigation, and telcos), Orbia margins and sales are about half of their historical average. Although the company is levered ($4.2 billion in net debt versus current $540 million in operating profits), interest payments are well covered. The company trades at a current earnings yield of 7.5%, which becomes 20% if the company returns to cycle-average margins. A burry play.

Argentina

EEM (81.45% of account, ~$41 cost basis): This is another parking position, just like FXI was on the US account, that I feel less compelled to sell despite the Chinese rally because I have no better options in the Argentinian market, and holding cash in a brokerage account represents a large fiduciary risk (the securities are held by the clearing house, but the cash is held by the broker). There is no big thesis really, simply that it was a large diversified ETF trading at historically low valuations, and potentially that emerging markets could benefit from a volatile inflation cycle (which may not have ended yet).

Lojas Renner (LREN3, 12.6% of account, ~BRL 12.5 cost basis)

Lojas Renner is the Brazilian Zara, the country's leader in fast fashion retailing. From a stylish perspective, I should say the company copies Uniqlo more, offering more basic products rather than fast-iterating designs. The company’s historical manager, José Galló, took the company from 8 stores in the early 1990s ($1 million market cap) to 665 today (more than $3 billion market cap). If he were American, he would also join the capital allocators pantheon.

Renner’s stock got hit by a mix of Brazilian inflation hitting on discretionary income in 2022 large credit losses (Brazilian retailers tend to give a lot of credit to customers, and the Central Bank took rates from 2% to 12% in 2023), and fears on competition from Shein. Brazil is very protectionist, which has caused incursions from previous fast fashion competitors to fail (the graveyard includes Zara, H&M, and Forever 21). Still, the de-minimis provisions represented a hole in the country’s protectionism.

Today, the credit issue has been moderated, and despite no modifications to de-minimis regulations, customers have moved back to Renner, which offers better quality for a slightly higher segment.

Banco Santander Brasil (BSBR, 6% of account, ~$5 cost basis)

My final position is another Burry story. Banco Santander was hit by the mix of higher credit losses as the Brazilian Central Bank increased rates from 2% to 12% in a year to combat inflation and by competition from neobanks like Nubank (NU) and Inter (INTR). The bank was trading a low P/B compared to its average ROE and growth.

The credit problem was solved with time as the financial system worked through the new rate level. Today, delinquencies are down, the cost of credit is lower, and the book is growing. As commented in my Primer on Brazilian Banks, I have a somewhat contrarian read on the Brazilian banking market. In my opinion, the neobanks will have trouble moving up from small retail and small businesses into affluent retail and corporate because those segments require much higher complexity than an app. They require more complex lending (mortgages, car, higher limits on credit cards), which in turn requires more deposits, which have to be obtained mostly from corporates (again opening a new front of required services). I think the traditional Brazilian banks will have a much easier battle in these segments (which are the creme of the market) than in low-service credit cards and deposit accounts.

My latest piece on Banco Santander Brasil is from July 2024.

Conclusions

This was the first time I've shown my portfolios in an ordered manner. You can expect to receive updates only quarterly, although I can probably share new and closed positions on Twitter and Substack Notes.

When writing about investment philosophy and markets, I said that investors should avoid high share turnovers. This would mean my quarterly updates should not update much, if I’m true to my words. However, given many of my current positions are of the Burry-type, they can have higher turnover, because they are not buy and hold type of stocks (although I can potentially hold to them for a long time, given that I am happy with the average yields).

I am happy with my results, but I am not happy with my portfolio. The turnover is one aspect, and another one is the excess of small positions. I am obviously out of ideas in some areas, which has led to a lot of ETFs and cash. Still, I am not anxious to be fully invested, as things will come, and time is on my side. I guess this unhappiness is part of building a healthy portfolio, and of being a little contrarian. Munger would say it is not supposed to be easy, and Buffett would say happy consensus have a steep price in markets.

Hope you liked this review, and that you found interesting ideas. Again, thanks for reading and sharing!