Stock markets are the enemy of investors

Liquidity, diversification, and financial theory are not good friends of investors.

There is intelligent speculation as there is intelligent investing. But there are many ways in which speculation may be unintelligent. Of these the foremost are: (1) speculating when you think you are investing (...).

Benjamin Graham - The Intelligent Investor

If you are reading this, chances are you consider yourself an active investor, as differentiated from passive investors or active traders. You try to pick stocks based on the value of the business and the prospects it holds for the future. You want to hold the stocks for the long term and avoid being moved by the whims of Mr. Market. However, you may be building your portfolio more like a trader than an investor, for example, by holding too many positions or trading in and out of them too often. This is hurting your results.

The problem arises from a confusion of terms. Today, everyone wants to be called an investor because it has cachet, even when they are following a trading strategy. The financial theory also equates investing with buying and selling financial assets. This led to investors picking up trading ideas and unconsciously incorporating them into their portfolio decisions. This article helps identify when trading ideas are entering the investment framework and how to remove them from the process.

I argue that if you are an active investor, it may pay to create a market-less environment by concentrating your positions and refraining from trading and looking at market quotations. Concentration increases the relevance of each holding, leading to an improved selection and allocation process to ensure only the best ideas get into the portfolio. Reduced trading helps investors focus on the factors affecting long-term stock returns, i.e., business and operations. I also argue that you should eliminate trading-based axioms from your investment theses, for example, ideas like alphas and betas, peer multiples, and market-based costs of capital.

This does not mean that the above ideas are incorrect. Rather, they work in the specific context of trading financial assets, not investing in businesses. Investors would be better served by having two separate portfolios: an investment portfolio with investment-based theses and a trading portfolio with trading-based theses. This ‘purification’ process will lead to better returns on both portfolios.

As always, if you liked this article, please help me share it. If this is your first time reading Quipus Capital, make sure to subscribe to receive articles on investment philosophy, industry primers, theme intros, and stock analysis. For the rest of the content, please visit the Index.

Disclaimer: This article is created with educational, discussion and entertainment goals only. I am not making, nor am I qualified to make, any investment recommendations to any individual.

Separating investing from trading

Investing and trading are fundamentally different activities. However, they are mixed in the context of stock markets because both investors and traders participate in them. Further, the two concepts are mixed because everyone wants to be called an investor (it is more honorable than being called a trader or speculator) and because financial theory has equated investing with holding a financial asset, which is something traders do. Therefore, let’s start by separating the concepts:

An investor buys assets expecting to generate an operational return from them. A trader buys assets to generate a return by selling them at a higher price later or in a different venue.

Notice that I didn’t mention stocks. This is because stocks are not necessary for investing or trading. A restaurant owner thinking about whether to open a second location is an investor. A thrift shop owner who is buying an old pair of Levi’s to sell them later is a trader.

Applied to stocks, an investor buys a stock to profit from the operational returns of the underlying business. A trader buys a stock to profit from the stock’s price increase.

Focusing on what’s important

It is clear that investors and traders think about stocks differently. Investors want to know how and why businesses generate profits and grow, and traders want to know how and why stocks go up or down.

But why is it that investors should focus only on business and not also on prices? Earlier this year, I wrote an article on the Epistemology of Investing, talking about why it makes sense (an epistemology is a theory of what can be known and how to search for that knowledge):

The human mind has limited information processing capacity and absorbs reality through the lens of perception. Human systems are complex in the sense that they have almost infinite features and volatile relationships between these features.

Market prices, in particular, are extremely complex systems with many participants operating with different goals, time frames, and constraints. Information in market systems has a short shelf-life, as it quickly becomes disseminated and incorporated in prices.

Investors focus on the long-term operational returns of businesses to eliminate price complexity and focus their efforts on finding knowledge with a longer shelf life.

On the other hand, we could talk of an Epistemology of Trading, which explains why it makes sense to focus on prices, and how to do so profitably:

Market participants try to discount the future. The result of their aggregate opinions is a more accurate forecast of the future than any of the players. Therefore the market is generally right.

However, information is not instantaneously transmitted to all players in the market, and therefore, prices take some time to adjust to new realities. Consensus, trends, bubbles and depression can also form out of missguided or slowly trickling information.

Because new information is semi-random (we don’t know what’s going to be tomorrow’s news), predicting new information is hard. Traders instead focus on predicting changes in consensus views (how others will react to probable future information), mispriced bets (scenarios where some probabilities are momentarily too low or too high), and arbitraging.

The two activities look for different types of information and operate with different rules about what can be known or not. This is turn leads to radical operational differences:

For the trader, certainty is almost never present. All trades can go wrong, and therefore diversifying and being nimble is important. Information is short-lived, so broad views are more important than detailed analysis.

On the other hand, investors work with processes that may last years, and where information has a long shelf life. Therefore, it pays for investors to research a lot, and find high conviction ideas, in which they ought to concentrate, to then let them mature via a lack of trading.

Trading axioms commonly incorporated in investing theses

Although indeed many investors live by the mantra of not allowing the market to interfere in investing decisions, trading ideas still find their way into their decision making methodology. When we incorporate them into the investment thesis, we weaken the soundness of the investment thesis, potentially leading to losing money:

Valuation multiples and peer multiples: if we believe that a stock ‘investment’ will be profitable because the valuation multiple will change, we are thinking of future prices, and therefore we are thinking of a trade. The multiple that should matter in an investor’s valuation is the inverse of the investor’s required rate of return (or normalized earnings yield). What one would pay for a business is independent of what others would pay for it in the future.

Market discount rates in DCF models: market views enter the DCF framework via the market-determined cost of capital, which is the inverse of the price at which stocks trade at some point in time. Although this is correct from the perspective of sell-side models, who have to work with average risk investors, it is incorrect for individual investors. The investor should discount cash flows using his/her own discount rate to value a stock, or conversely, find out the rate of return offered by a stock given its current price and future potential earnings.

Volatility as risk: in most financial models, risk is defined as price volatility, be it standard deviations, betas, etc. How much a stock price will move during some period of time is a trading question. For investors, risks are not related to market activity and volatility, but to business operations.

Alpha, or the excess return over risk, stems from volatility as risk and is, therefore, also a trading concept. For an investor, there is only absolute return and risk, without consideration for alpha or beta.

Business owners don’t think of beta.

Trading-based frameworks become much more evident when comparing a public equity investor with a private investor, such as a business owner or a private equity manager. Active public investors should try to incorporate these practices into their portfolio-making activities:

Patience: a business owner is not expecting to make a killing in a year (unless he is a private trader, say, flipping real estate). Rather, he understands that things take time, including periods during which accounting results might not be great. In contrast, public equity holding periods shrink by the day.

Operational knowledge: successful business owners and private investors know their markets inside out: players, products, qualities, prices, customers, and trends. In contrast, many public equity investors think a one-week research project is a deep dive into a company or industry.

Skin in the game: the average number of holdings for a private equity fund is less than ten. Most business owners have the majority of their wealth in a single enterprise. This makes them pay attention because otherwise, they are toast. In contrast, public investors can easily have 20, 50, or 100 stocks.

Creating a market-less environment

Investors should purposely create a market-less environment for themselves. This involves:

Remove market-based axioms from the investment thesis (referred above, like peer multiples, betas, volatility as risk, etc.)

Refraining from looking at quotations or reading market news, which are most often only sources of noise.

Concentrating their portfolios to increase the importance of each position leading to a more thoughtful and complete decision-making process.

Establishing trading limits, also to increase the relevance of each position, and to avoid falling victim to market gyrations.

As these actions make the investor much more mindful of capital allocation decisions, they should lead to better returns over the long term.

I am not calling for the elimination of all trading activity in a portfolio. Rather, I am calling for a separation of activities. The big losses occur when we believe we are investing but we are actually trading.

I am also not saying that public equities are bad. Markets are a great tool for investors, especially for those of modest means. Without public equities markets, we could not access a piece of the action in outstanding companies. However, markets bring trouble to investors when they become the focus instead of a tool.

Avoiding price quotes and news

When I see an investor monitoring his portfolio with live prices on his cellular telephone or his handheld, I smile and smile.

Nassim Taleb - Fooled by Randomness

Daily stock quotations and financial news are generally just noise, not information. Looking at them sucks the attention and focus that are paramount to investors. A great example is what happened a few weeks ago with the Japanese crash, followed by a violent rally, only to go back to the starting place.

Making a correct investment decision requires pondering long-term events and forces, incorporating much information, and processing it rationally. It also requires patience to sift through many ideas without finding an opportunity and then wait for the business to perform once the investment is made.

Focus and patience are increasingly hard to obtain in a world where Meta and Douyin are trying to transform us into attention cows. Cultivating these traits requires consciously refraining from dopamine-triggering activities, like watching our phones or looking at emails. Looking at quotes and reading or listening to market news has a similar ‘novelty’ effect to that generated by scrolling through Twitter or Instagram reels. But that novel information is worthless for investment decisions, and we should ignore it.

Further, daily quotations and daily news are noise anyway. Nassim Taleb perfectly exemplifies this in Fooled by Randomness. Imagine a dentist who is a fantastic investor. Her returns have a mean of 15% with a volatility of 10%. Her probability of landing a positive year is 93%. However, her probability of landing a positive day is only 54%. This means that if she looks at quotations every day (little compared to how often most people look at prices), she will feel miserable, dumb, and doubtful almost half of the time. One in three months will be negative, making the pain even worse.

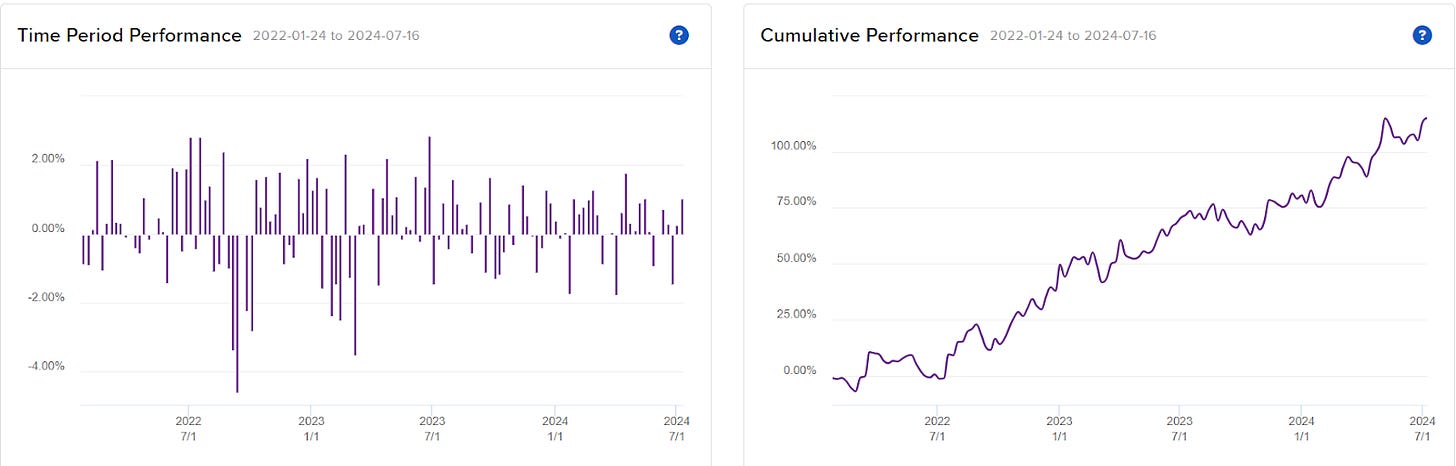

As an example, look at my portfolio on a weekly vs cumulative basis below. Weeks are basically random. They can do very well or very bad. Yet every quarter I end up positive (so far of course).

*As a side note, there is so much irony in Nassim Taleb’s current Twitter addiction.

Concentrating the portfolio

The strategy we’ve adopted precludes our following standard diversification dogma. Many pundits would therefore say the strategy must be riskier than that employed by more conventional investors. We disagree. We believe that a policy of portfolio concentration may well decrease risk if it raises, as it should, both the intensity with which an investor thinks about a business and the comfort-level he must feel with its economic characteristics before buying into it. In stating this opinion, we define risk, using dictionary terms, as “the possibility of loss or injury.”

Warren Buffett - Berkshire meeting 1993

Diversification is good but not fundamental for successful investing. Further, a diversified portfolio does not require too many stocks. Having many positions leads to sloppy thinking and gambling tendencies. Investors should concentrate their portfolios to increase the importance of each position and, therefore, require more safety when investing.

The main roles of diversification in a portfolio are to decrease volatility and reduce the damage caused by a position blowing up. For traders, these are important characteristics, as the risk of any trading position going wrong is high, and because trading portfolios are generally leveraged. But for investors, these characteristics are not as relevant.

But volatility is totally unimportant for an active investor. Prices can go up and down in the short to mid-term, but the investor should care only about the performance of the businesses in the portfolio. Of course, seeing the stocks go up and down can be pleasant or painful, but that is why we should not look at quotations that much. Ignoring volatility is part of an investor’s mental training.

In this respect, the number of stocks in a portfolio does not matter for volatility-diversification purposes. What matters are the factors built into the portfolio. If one has 100 oil stocks, the portfolio will not be as diversified as one with 10 positions in different industries and regions. However, the reader should be aware that factors are pervasive and that during market stress, correlations increase, meaning even the most diversified portfolios can move in tandem.

The risk of a position blowing up is a different thing. There are many ways in which a good-enough business idea can fail: an act of god (like COVID for airlines), the thesis was incorrect, or the price paid was too high. That is why the margin of safety, due diligence, and research are so important. One should be sufficiently sure that the conditions of a business will not change dramatically in the future and ask for a stock price that does not require super-optimistic assumptions to work out.

In this respect, diversification is the enemy of the investor, and concentration is a friend. If investors know that a stock will represent 15% of their portfolios, they will be much more stringent in selecting. They will try to talk to as many people in the industry as possible about the business, the environment, the competitors, etc. They will require that management is impeccable. And they will ask for a good price on the stock. The opposite happens with a diversified portfolio. When positions are 3% of the portfolio (or worse, measured in bps), the investor starts to act like a speculator, requiring much less certainty and making lots of bets. I call this the ‘gambling tendency’ in investing. The recent popularity of odds markets makes this tendency even worse.

Creating artificial illiquidity

The big money is not in the buying and the selling but in the waiting

Charlie Munger

The possibility of selling stocks every day is damaging to investors because it generates anxiety and leads to a trading mentality. One way to combat this is by establishing an illiquidity rule via minimum holding periods or established selling windows.

Here, financial theory mixed with investing is the culprit again. In financial theory, the zero-based budgeting framework says that all positions should be reconsidered every day against all potential allocations to find the true optimal allocation. That makes theoretical sense but is practically impossible except for quantitative trading strategies.

On the contrary, I believe investors should set rules to avoid trading on the way up or the way down. This improves the process before and after buying the stock.

Before the investment, artificial illiquidity generates the same effect as concentration. The investor will necessarily put more effort and thought into the ideas if the stock cannot be sold during X period, even if things go wrong temporarily.

After the investment, artificial illiquidity helps avoid anxiety-induced decisions. When stocks are moving, it is very easy to rationalize that selling is the right choice. For example, quarterly earnings are not as good as expected, and the stock opens 15% down. Investors can find five reasons to sell in the quarterly results and earnings call. It is easy to sell into market strength, too. The stock is up 20% in two months, and the investor fears that the stock will then correct. The investor can then rationalize selling to accumulate more on the way down. These seemingly rational decisions are trading mentality at its finest. Stocks move up and down 20% several times a year sometimes, and it is extremely difficult to predict those movements.

Investors can generate selling illiquidity with two methods. One is minimum holding periods. For example, determine that a stock can only be sold after a holding period of one quarter, one year, two years, or five years. The problem here is actually enforcing the strategy after buying, so I recommend increasing the minimum holding period in stages. This is the idea behind methodologies like the coffee can method (buy stocks you can put inside a coffee can and only sell in 20 years) or the punching card method (think as if you could only buy 20 stocks in your whole life). The second method is to determine activity windows or activity conditions. For example, stocks can only be sold after Q4 earnings or only if they cross a specific price that is considered a sufficient target. These conditions should be set in advance.

A continual process of improvement

Many would correctly say that following the above recommendations implies leaving money on the table. The market-less philosophy does not cover some profitable corners of the finance practice: special situations, turnarounds, cyclicals, spin-offs, net-nets, etc. All of these profitable areas are in the realm of speculation because there is no intention to buy to hold, only buy to sell (maybe after five years, but still buy to sell). Still, they are informed by deep business knowledge. Further, many pure speculators have been tremendously successful.

But paraphrasing Graham, there is intelligent investing and intelligent speculation. The unintelligent is to speculate when we think we are investing, or vice versa. The above recommendations help draw a clearer boundary between the two and act accordingly. Even more, focus, concentration, and illiquidity also help improve performance in speculative situations. The urge to sell a laggard cyclical or net-net can be arrested by artificial illiquidity. The requirement to put large positions can help improve the research behind a turnaround.

Finally, I think these recommendations are benchmarks or milestones. Building a strong investment process is an ongoing practice. I generally walk off the trail, adding small speculative positions in the search for a quick buck. They may end well but at a high psychological cost. The worst performance has been created by the investing/speculation mix, the stocks of not-great businesses that I buy because their multiple is one or two notches below what I think is fair value, that end up drifting sideways forever. I think that over time, I will dedicate most of my time to only a few ideas and have a concentrated portfolio with a turnaround of several years or maybe even decades. At least that’s the goal.

As always, if you liked this post, please help me share it! If you haven’t subscribed yet, now’s the time! I write about investment philosophy but much more about industries, trends, and companies, you can check the rest of my work at the Index.

Beautiful read, much food for thought.