LatAm Food Products: Bird's Eye View

I have been delving into Latin American food companies in the past month and a half. These include agricultural producers like SLC Agricola, Brasilagro, or JBS and manufacturers like Grupo Herdez and Grupo Nutresa.

The list is not comprehensive as I have focused solely on names traded in the US directly or via ADR (despite the low volumes traded in this segment in most names).

My general conclusions are:

Some Brazilian meatpackers (JBS and Minerva) present substantial opportunities, as these names have amassed substantial market power. Yet, they trade at relatively low cycle-average valuations because of financial concerns and a depressed Brazilian equities market. BRF is not an opportunity, as it has suffered from operational problems and bad capital allocation.

Agricultural producers, particularly farmers, and land-owners like SLC Agricola, Brasilagro, Cresud, or Adecoagro, are either unprofitable during commodity bear markets or trade at relatively high (10+) multiples of cycle-average earnings, which is not justified for companies that cannot grow without substantial capital expenses. The recent uptick in commodity prices seems to inflate the land valuations. These names are not long-term holding investment vehicles, but rather commodity price speculation vehicles IMHO.

Large food packagers like Gruma or Herdez have substantial market power in their segments, albeit challenging macro conditions across Latin America have probably muted their growth.

Based on their recent accelerated growth trends, they currently trade at relatively high forward earnings estimates. I believe these trends are not necessarily sustainable but reflect a rearrangement of margins after the 2021/22 inflation bout.

List

Brazilian meatpackers

JBS (JBSAY)

Minerva (MRVSY)

BRF (BRFS)

Farmers

Cresud (CRESY) and Brasilagro (LND)

SLC Agricola (SLCJY)

Adecoagro (AGRO)

Packaged food

Gruma (GPAGF)

Herdez (GUZOF)

Nutresa (GCHOY)

Brazilian meatpackers

The central thesis around Brazilian meatpackers is that they have amassed enormous market power, particularly on the supply side (monopsonies or oligopsonies). They control the facilities to which most Argentinian, Brazilian, or American ranchers have to sell. In the case of JBS, that dominance is also translated to pork and poultry. Further, having a presence in many producing and selling countries (or, in the case of JBS, across proteins) gives these companies some degree of diversification against cycles.

This market power and diversification has shown up in generally consistent profitability across the commodity cycle and growing ROCE figures.

Minerva's article published on Substack provides a more detailed description of the sector thesis.

The opportunity arises because of a combination of:

The BRL depreciation has generated large accounting and non-cash losses on these relatively leveraged companies, depressing net income. Given the companies ' exposure to dollar-denominated revenues, I believe the leverage is not a source of risk.

Short-term margin compression in some protein markets, particularly the US.

Generalized depression in Brazilian equities.

JBS (JBSAY)

A complete standalone article has been published on Seeking Alpha.

JBS is the largest meat exporter in the world and the largest public food company by revenue. It is difficult to exaggerate its gigantic size in cattle, pork, and poultry.

Its margins and ROCE have grown cycle after cycle since before the 2010s.

Its geographic diversification makes it less exposed to anti-monopsony or geopolitical risks.

Its low cost advantage upstream and gigantic size are two great assets to develop in higher margin lines downstream

Its owners are in good standing with both sides of Brazilian politics

The company is less leveraged than other protein players. Has issued fixed debt maturing in 2053.

It trades at 7x cycle average net inc or 7x EV/avg-EBIT

Minerva (MRVSY)

A complete standalone article has been published on Substack.

Minerva concentrates on Latin American beef (it has small operations in Australian and Chilean sheep). Therefore, it is less diversified and smaller than JBS, but it still has market power in the regions where it operates.

Minerva has a huge market share in beef exporting in Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Colombia. After (and if) the acquisition of Marfrig’s assets is approved, it will have close to 40/50% share in all these markets.

South American beef has competitive advantages over the other main exporting markets (US, Australia, India). Beef consumption is increasing globally.

The company has large, long-term-oriented shareholders, including the founding family and a Saudi Arabian sovereign fund.

BRF (BRFS)

A complete standalone article has been published in Seeking Alpha.

BRF is a huge player in chicken, swine, and processed products, with Brazil's most valuable meat brand (Sadia).

Unfortunately, the company has not been good at capital allocation. Operating margins have trended down, debt has gone up, and the company has divested many of its former acquisitions at a loss.

I believe the reason for this underperformance compared to JBS or Minerva is the lack of large controlling shareholders involved in management. Marfrig only took a large position in BRF after 2020.

BRF is much more unstable, given that it generates operating losses, and its debt coverage ratios are lower than those of Minerva or JBS.

Farmers

In my humble opinion, a commodity cyclical company can be interesting for long-term investing (and not commodity price speculation) under some scenarios:

The company is a low-cost producer and has shown that it can stay profitable and solvent during the bottom portion of the cycle.

Its managers have shown that they can deploy capital countercyclically.

The company trades at a discount to cycle-average earnings, maybe adjusted for growth in producing assets (hectares, heads, etc.).

Among the farmers analyzed, Cresud and Brasilagro fulfill none of conditions, whereas SLC Agricola passes all but the last test.

Cresud (CRESY) and Brasilagro (LND)

A complete standalone article on Cresud has been published on Seeking Alpha, and the same for Brasilagro.

Cresud is an Argentinian conglomerate that owns agricultural lands in Argentina, real estate in Argentina (via its controlled Irsa, ADR IRS), and agricultural land in Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia via its participation in Brasilagro (LND).

For Cresud, my analysis compares profitability and land values with or without export taxes that have been in place since the early 2000s in Argentina. The bullish claim is that these taxes will be removed, and under that assumption Cresud is indeed cheap, but not so if that is not the case. Investing in a currently expensive company in the expectation that an outside event will render it cheap is an speculation, and I’m not good at it.

In the case of Brasilagro, the bullish stance compares the company’s EV with the fair value of the company’s net assets (specifically the fair value of land). Again, that argument yields an undervalued company. In this case, I believe the problem has to do with the correlation between land values and commodity prices. The fair value of Brasilagro’s land did not move between 2012 and 2018, with commodity prices crashing, to then explode after 2020, in line with commodity prices. The same happened with the (negative or breakeven) operational profitability of the farms. With high grain prices, Brasilagro is cheap, with low prices it’s either expensive or fairly valued. Brasilagro has no control over grain prices, which makes the stock purchase a form of speculation.

SLC Agricola (SLCJY, SLCE3.SA)

SLC Agricola S.A. is a Brazilian soybean and cotton farmer, cultivating 670 thousand hectares in the Brazilian cerrado (440 thousand actually, plus 230 thousand that are sown a second time).

Going back to the conditions for interest in commodity cyclical companies, I find that SLC Agricola is not an opportunity.

SLC Agricola indeed seems to be a low-cost producer for a few reasons:

its median productivity is higher than the world average and the Brazilian average. This could be explained by natural factors like soil and irrigation that can be arbitraged via rents, but …

the company owns half of its cultivated lands, meaning it can appropriate that rent and doesn’t need to pay for it. The other half is leased, and probably this segment is much less profitable.

the company has been profitable across the cycle, at least since 2012.

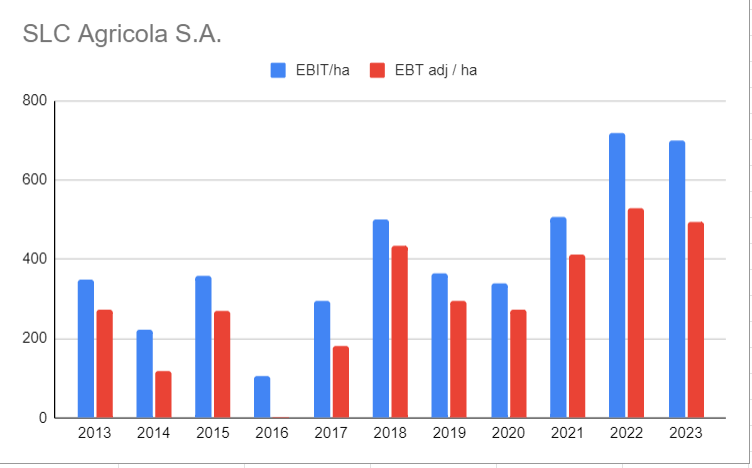

Finally, for the last point, there are two ways to think about this, although I believe that both measures ($114 or $130 million) are too small for a market cap of $1.6 billion:

SLC generated an average of $114 million in net income since 2013.

The company also generated an average of $296 EBT adj/ha since 2013, or $192 after 35% Brazilian income taxes, which applied to the current cultivated area of 674 thousand hectares would yield $130 million approximately.

I use EBT adj because EBIT underrepresents the financial cost of leases, which increased after 2021, and because there are nonrecurring charges in net income that would complicate the calculation.

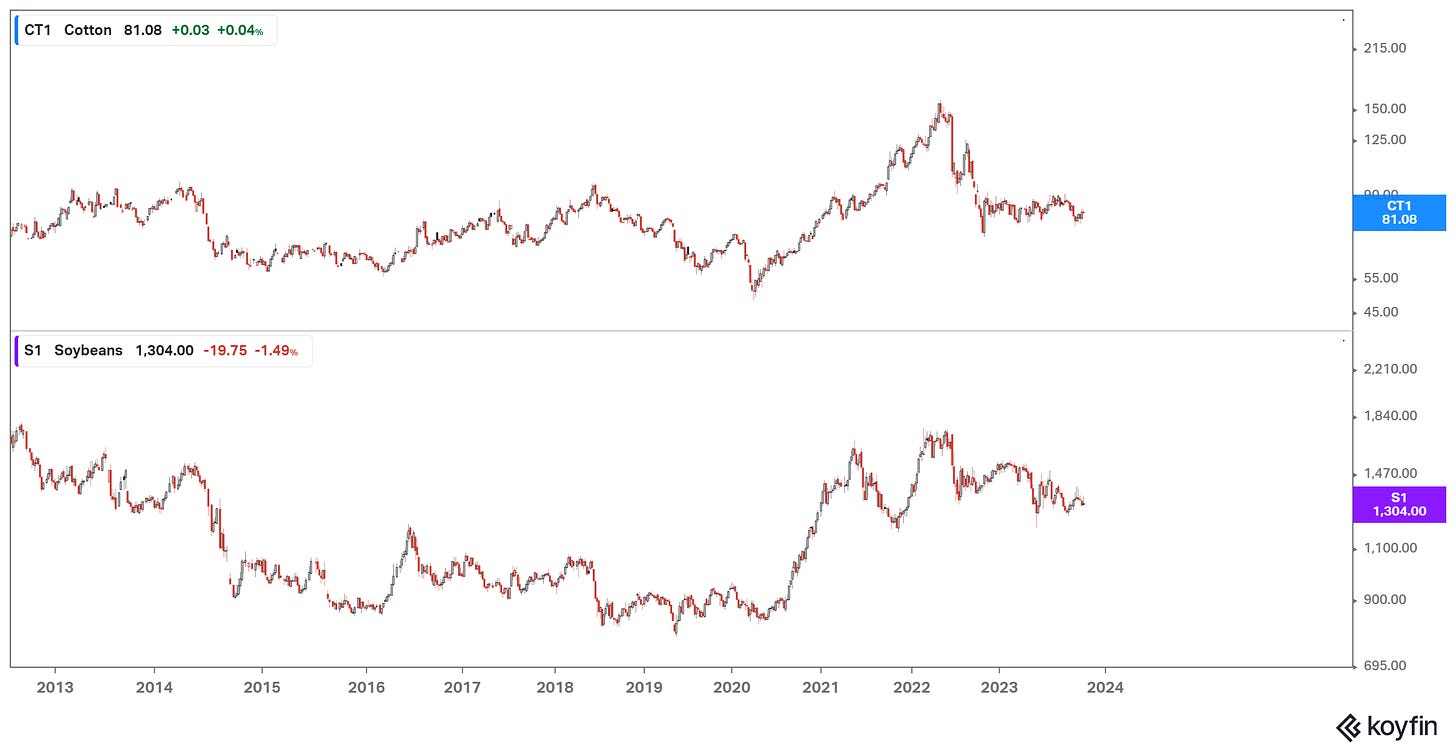

It is also interesting to see the correlation between profitability per ha and the commodities, especially cotton.

Some people would point to the fact that SLC has a lot of land it carries at cost on its books. The company claims it has $2 billion in land value, which is only registered in the books at a $400 million valuation. That alone is higher than the company’s market cap.

In my opinion, the problem with that view is that the company is not planning to liquidate, so it makes no sense to value it on assets alone. If it sold and leased back those lands, then its EBIT adj/ha would be lower because a portion of the profitability would be paid as rent.

Adecoagro (AGRO)

A complete standalone article on Adecoagro has been published on Seeking Alpha.

Adecoagro started as an Argentinian land development play in the early 2000s, and correctly timed the commodities bull market, coupled with technology improvements in grain cultivation. The company quickly expanded to rice and milk production in Argentina, integrating production, processing, packaging, and branding. It also added sugarcane plantations and processing in Brazil.

Brazil's sugarcane and ethanol business quickly became the company's breadwinner, providing 80%+ of EBIT for most of the past decade.

Adecoagro complies with my requirement that commodity companies remain profitable even during the bottom portion of the cycle. It did not invest countercyclically, preferring to buy back shares during the 2012-2020 bear market.

The problem is that it trades at a high multiple of cycle-average NOPAT or net income. It does not offer a large discount to net assets either, only about 20%. Just like the other farmers, it seems that this stage of the commodities cycle is not the best to look into farmers unless one has a bullish commodity price bias.

Packaged food

Gruma S.A.B. de C.V. (GRUMAB.MX, GPAGF)

Gruma is one of the, if not the largest, corn flour millers in the US and Mexico. The company has a leading position in corn tortilla products in the US, whereas, in Mexico, it has a small share in tortillas and a smaller share in flour because it competes with the strong Mexican MSME economy. It also has adjacent operations in Europe and Asia.

The company’s position is strong and commands a high multiple that has generally ranged between 15x and 20x P/E for most of the past decade.

Gruma could not grow revenues or profitability consistently for most of the past decade, and this should not be tied to the Mexican economy, given that 60% of the company’s revenue comes from the US market.

Very recently, the company’s operating income has jumped significantly, maybe triggering questions about whether or not the Gruma is growing again.

In my opinion, Gruma’s case is an excellent example of a company that can benefit from inflation to grow profitability one time because it sources a commodity and sells a brand. This also means I believe Gruma will not be able to keep this profitability growth in the future.

Gruma’s financials show that the company’s revenues started picking up fast after the pandemic, whereas its operating income lagged, with falling margins. Gruma was raising prices, selling the same volumes, but barely recovering the cost increases it faced.

The magic came after 2H22, when input prices (mainly corn representing more than 30% of costs) started to fall, while at the same time, the ‘new normal’ prices at the retail level remained high, allowing the company to recover margins. The rest of the magic came from a revelation of the MXN against the USD, as visible when comparing operating income in MXN vs USD.

Why is this possible? Because most of Gruma’s sales (tortillas in the US retail market) are to customers that are much less sensitive to prices returning to their mean via input, than to the average price of all alternatives in the category. At the same time, the markets where Gruma sources its inputs are much more competitive.

I would expect that if input prices continue falling, Gruma can recover the remaining portion of its median operating margin, after which operating income will stop expanding.

Grupo Herdez (GUZOF, HERDEZ.MX)

Grupo Herdez is a large packaged food manufacturer from Mexico. The company didn’t attract my attention a lot because it has an intricate JV and subsidiary structure, where most profits are generated, which is difficult to understand. Because the company trades at a relatively high multiple of earnings (both pre and post minority interests) I prefer to put it in the too-hard pile.

The company owns or licenses several well-known mole, guacamole, pasta, tomato sauce, jelly, and tea brands. It enjoys more than 50% market share in those markets in Mexico. It also dominates the export market for mole (a Mexican sauce). Besides these product leaders, it works with more than 25 brands.

Grupo Herdez has three segments: preserved food, impulses, and exports.

The company’s leading segment is preserved foods, with 80%+ of profits and revenues. The leading products, in terms of revenues and profits, are pasta, mayonnaise, and tomato sauce. These lines are carried in consolidated subsidiaries (50% ownership) with Barilla (pasta), McCormick (mayonnaise), and Del Fuerte (tomato sauce). The subsidiaries pay royalties to the brand owners on top of sharing profits. Most of these details are not well disclosed in the financial statements, besides a minority interest line.

The export segment follows in profitability, here the local brands of Mole and guacamole are the revenue drivers. Still, most of the export business is only owned at 25% despite being consolidated because Grupo Herdez has a 50% subsidiary with Del Fuerte, which in turn owns 50% of the exporting subsidiary.

Finally, the impulse segment owns a completely unrelated line of store business and franchises in much more perishable products: frozen yogurt, ice cream, and botanas (Mexican snacks).

The consolidation of the large profitable segments has in a certain way hidden the lack of progress in the company’s own brands. Despite the group tripling revenues, more than doubling gross profits and close to doubling pre-tax income in the past ten years (in Mexican pesos), net income to majority shareholders has stagnated completely.

When measuring the company in US dollars, one should be careful to incorporate the significant effects of the Mexican peso depreciation from 2010 to 2020 and appreciation since.

The company trades at an EV/NOPAT multiple of 13x which translates to a P/E of 20x+ when the minority interests are considered.

Grupo Nutresa (GCHOY, NUTRESA.CL)

Grupo Nutresa is a large food manufacturer from Colombia. The company seems to have a good branding position across several categories and large operations in other countries of the Americas.

The company’s financials are difficult to find; it seems that it is undergoing a Public Acquisition Offer by one of the controlling shareholders; and it trades at 30 times earnings and 20 times EV/EBIT despite not being able to grow in profitability in more than a decade.

I’ll put it in the too hard pile.