Minerva S.A.: Rise Of A Monopsony

The Brazilian meatpacker is becoming the leading player in the South American and global beef export markets.

Disclosure: I own ADRs of Minerva S.A (I do not own any as of this article’s publication). Minerva’s ADRs are not liquid.

The painting is from Frans Post.

TLDR;

In this review, I will talk about Minerva S.A. (BEEF3.SA, US ADR MRVSY), South America's largest export beef meatpacker.

In my opinion, this Brazilian company is interesting because:

Export meatpacking has high barriers to entry, primarily because of the complex country-by-country and facility-by-facility authorization process.

The company enjoys several types of scale advantages

Minerva has a huge market share in beef exporting in Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Colombia. After (and if) the acquisition of Marfrig’s assets is approved, it will have close to 40/50% share in all these markets.

It is a monopsony or oligopsony in most regions where it operates inside each country. This trend would increase with Marfrig’s assets acquisitions.

Minerva can arbitrage across many factors: climate, feed costs, credit availability, qualities, import permissions, etc.

Diversifying across exporting regions and countries can offer its customers higher supply security and supply chain simplicity.

As a middleman, the company does not suffer as much from the acute price cycles of the commodity.

South American beef has competitive advantages over the other main exporting markets (US, Australia, India). Beef consumption is increasing globally.

The company has large, long-term-oriented shareholders, including the founding family and a Saudi Arabian sovereign fund.

Further, currently, the stock is an opportunity because of what I believe are misinterpreted earnings:

Minerva has USD-denominated debt. With BRL as the functional and presentation currency, it records non-cash losses when the BRL depreciates against the USD. These losses have been significant and consistent because the BRL has depreciated from 0.6/USD in 2012 to 0.2/USD in 2020.

Those expenses would not be recorded if the company's accounts were presented in USD. The same company, but using USD as its functional currency, would show much smaller financial expenses.

When this effect is removed (or if cash accounting is used) the company presents interesting profitability metrics. Further, it trades at what I consider to be low multiples of post-acquisition after-interest earnings.

Let’s deal first with the operational and market aspects and then with the financing and accounting.

The commodity traders’ role

In the book ‘The World for Sale,’ Javier Blas and Jack Farchy describe the stories behind the largest commodity traders of the 20th century, focusing mainly on oil and metals.

Across trading firms and commodities, the main business of the traders is to arbitrage on information, relationships, and supply. This activity is necessary because too many sellers, buyers, qualities, and geopolitical interests are involved.

The export beef market has the characteristics that allow for such arbitrages:

Atomized sellers: In Brazil, establishments with less than 50 heads control 75% of the country’s herd. These sellers have a shortage of working capital, lack of transportation, and lack of market-wide information.

Cyclical production by regions: different regions will be expanding or reducing production at the same time. These regional cycles are caused by climatic factors (rains and availability of pastures), input costs (particularly feed), and an elongated production process (three years from breed to slaughter). The beef cycle is well studied, and its leading indicator is the percentage of females slaughtered. When ranchers have a high cost of maintenance (lack of pastures or high feed costs) and low prices, they stop investing in calves and kill the breeding females. When prices are high, ranchers keep the females pregnant to grow their herds.

Complex sales by origin process: countries put a lot of requirements on meat imports because it can be a vector of disease and also for geopolitical and protectionist reasons. Only specific meatpacking facilities can export to specific countries, and these authorizations can be turned on and off. Importing countries play geopolitical games with the exporting countries, allowing them more or less ‘quotas.’

Scale and market power

Minerva concentrates mainly on beef export meatpacking facilities in South America. Exports have made up close to 70% of revenues for several years. The company has also invested in sheep meatpacking in Australia and Chile and beef industrialized products in Argentina, but these are small, adjacent, and, in my opinion, unimportant businesses.

The company has achieved substantial scale and market share in the export market. It concentrates more than 70% of beef exports in Colombia, more than 50% in Paraguay, and more than 30% in Brazil and Uruguay. Globally, it represents 20% of South American beef exports. Further, after acquiring Marfrig’s assets (and if the authorities in Uruguay and Brazil approve the acquisition), it will increase its share to 50% in Uruguay and close to 40% in Brazil, representing close to 30% in the region, and the largest exporter in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Colombia. Management has recently stated its interest in reaching 50% market share.

This scale further compounds the competitive advantages that a commodity trading company requires:

In Paraguay, Colombia, and increasingly Brazil and Uruguay, the company is a monopsony or part of an oligopsony. If we dug further into regions inside the countries (beef is expensive to transport alive), Minerva is probably the single buyer in many South American regions. A Brazilian study of concentration in the meatpacking industry found that prices paid to ranchers are 30% lower in monopsonistic regions.

Minerva can gather granular and real-time market information for every beef-producing region in South America. This includes climate, supply and prices across qualities, capital and liquidity availability of ranchers, etc. With this information, it can concentrate on buying in specific regions with excess supply. This information arbitrage has been in the company’s DNA since beef truckers founded it. Minerva’s CEO (member of the founding family) recently commented that he remembers how his family received telephone or telegraph messages from their truckers in the 1960s and 1970s, informing of conditions in different Paulista towns that did not have telephone access.

The company can arbitrage and swap beef from different countries to the same buyer if both facilities are approved. For example, a facility in Paraguay is authorized to sell to the UAE and Taiwan, while a facility in Brazil is authorized to sell to the UAE and mainland China. Taiwan prices are low, so Minerva can shift some of its Brazilian exports to China and increase UAE exports from Paraguay. There are many other examples, like Paraguay’s freight being more expensive than from Brazil, Paraguay having excess supply, Paraguay’s export quota to country X being overfilled, etc.

Buyers of beef, especially countries or companies concerned about not having shortages, can find greater security in Minerva as a supplier. If a specific country has a supply shock (climatic, freight, disease, meatpacking authorizations), Minerva can supply from a different country or facility. This occurred, for example, in 2023 when China momentarily banned Brazilian imports. Minerva’s sales to China did not decrease because it was able to fulfill from other regions.

Global buyers like retailers can find a single supplier that simplifies their beef importing process across several countries, regions, and qualities. A Walmart or McDonald’s can get different qualities (from Brazilian Zebu to Argentinian Angus) in UAE, Singapur, or Germany, all from Minerva.

Minor scale advantages like consolidation of sales offices in buying markets, export offices, managerial expenses, etc.

There is a reality that contrasts with this theory, though. Minerva’s operating margins have not increased since 2012 despite the company doubling its capacity. For this reason, I consider the above only a theory and do not incorporate it in a fair value calculation.

Low(er) cyclicality

Cyclicality is a big problem with commodity industries, and beef is no different. The industry suffers from long cycles (moderated by female slaughter percentages) and short cycles (moderated by feed prices and pasture availability) by regions.

Minerva has not been as affected by these cycles for three structural reasons:

As a trader, it is affected by volumes rather than prices, which are the clearing factor in commodity markets.

Depending on relative supply, it can shift focus between regions that offer more or less competitive prices. As long as excess supply and depressed prices are prevalent only in specific regions, the company can benefit from buying in these regions at depressed prices and selling in international markets.

South American beef has a price advantage over its American and Australian counterparts consistent across the cycle because most South American beef is pasture-raised and, therefore, cheaper to produce. This price advantage moderates South American cyclicality because volumes are more easily cleared. South America makes up 40% of the global export supply.

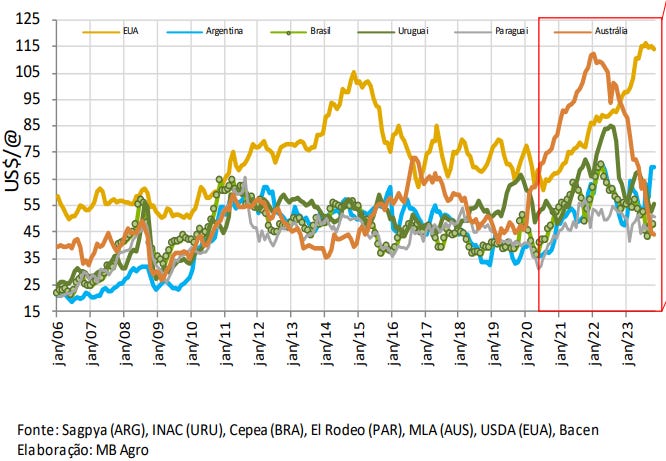

In the chart below, one country is missing: India, a huge player (20% global market share) and specifically a competitor with Brazil, Paraguay and Colombia). Another aspect missing is qualities, as the prices are per head. If Argentinian or Uruguay beef costs the same as Brazilian or Paraguayan, the former is better priced because quality is superior.

Export beef prices by region - Minerva’s 2023 Investor Day presentation page 80

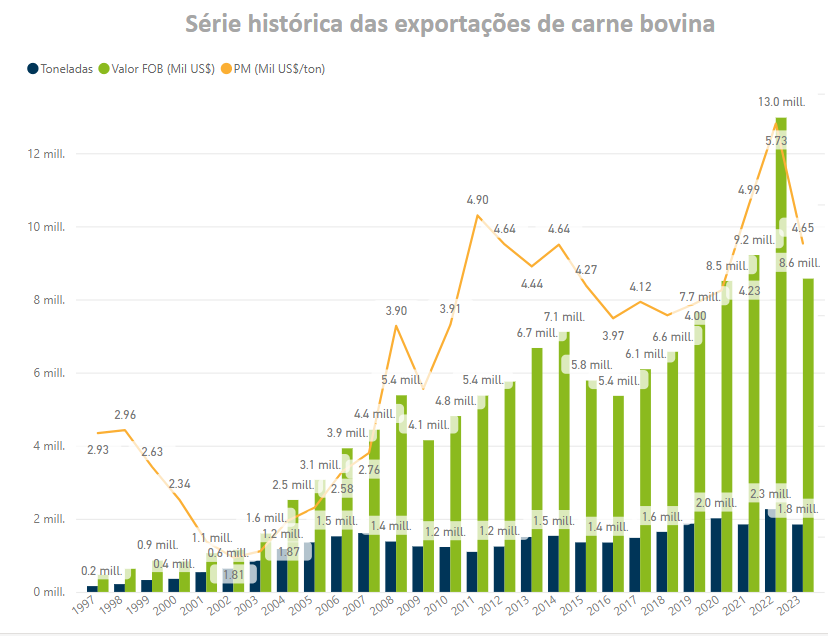

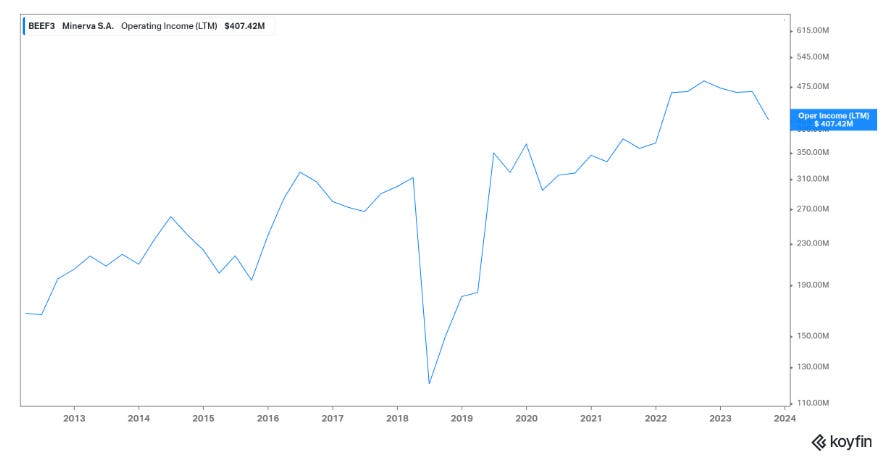

One data piece supporting the low cyclicality exposure idea can be found by comparing Brazil’s beef export figures with Minerva’s operating income.

The first chart below shows Brazilian beef exports in tons (blue), total FOB value (green in thousand dollars), and the median price per ton (yellow in thousand dollars). It shows a 25% fall in total exported value between 2014 and 2017, followed by a 300% increase between 2017 and 2023.

But Minerva’s operating income in USD below did not move with the Brazilian cycle. The fall in 2018 is caused by the recognition of labor-related taxes in Brazil after a 20 year plus legal battle, and not by actual recurring operations.

Additional competitive considerations

There are some aspects that I believe are not as important today but that will be interesting to follow in the future:

Minerva’s less penetrated market is Argentina, a country whose herd has been stagnant or decreasing for decades but has one of the highest quality beef and, as seen above, a price advantage. If Argentina begins an agricultural boom cycle thanks to more market-friendly politics, it could compete with Uruguayan and even Brazilian beef. Minerva’s next acquisition should be in Argentina.

India is also a formidable competitor to Brazilian, Paraguayan, and Colombian zebu beef. India’s cattle herd and beef exports have been stagnant for several decades. It also has a much larger population than Brazil, meaning lower potential surpluses. However, it could play a very interesting role in the future. It would be interesting to see Minerva in that market as well.

Brazilian beef has been under heavy scrutiny because of ESG concerns. Cattle are raised in the lower-quality lands of the country’s northeast and center-east, in terrains that have sometimes been taken from the rainforest. Minerva claims to have systems to track that its supplies do not come from illegally deforested terrains, but this is a source of reputational risk. Also, most of the company’s revenues are not from ESG-stringent regions. EU and NAFTA represent 15% of exports (10.5% of revenues) in LTM3Q23. I believe that ESG import restrictions will be applied more by countries that want to defend their ranchers (like the US and EU).

Brazil still has the potential to increase its beef production. The country is still behind in many productivity techniques like better grassing rotation, a mixture of pasture and feedlots, and genetics. It is believed that almost 30% of deforested land is not being used and could potentially increase pasture capacity.

Some operational figures

Above, we had operating income increasing consistently for over a decade, almost unabatedly. Here, I list more operating figures that the readers can check independently. Unfortunately I still don’t have purchased charting tool licenses.

The company’s revenue has tripled since 2012, from $2 billion to $6 billion.

Gross margins have been remarkably consistent, around 18% and 20%. This is very different from a commodity-producing company.

Operating margins rose from 5 to 10% between 2007 and 2012, but since have decreased to 8%. One fundamental problem with my theory is why operating margins have not increased with market share.

Minerva’s ROCE (operating income over total assets) has been above 10% as well, ranging between 9% and 12% since 2012 (excluding the 2018 tax event).

Cash conversion has been solid with 10% plus average CFO to revenues margins.

The company’s FCF (removing interests, given that IFRS companies put interest expenses in financing cash flows) has shown an increasing trend since at least 2016 and has been positive since 2019.

Further, most of the company’s CAPEX has been expansion, not maintenance CAPEX, so the potential FCF margin of the company is higher. The company’s CAPEX to D&A has been above 1.5x since 2018; before that, it was above 4x.

The Marfrig assets acquisitions

Minerva has acquired more than 15 companies since going public in the 2000s. A large portion of its expansion has come from acquisitions.

I believe that the fact that ROCE was kept consistent despite the acquisitions and asset expansions shows that the company has been able to integrate the acquired companies well.

The latest announced acquisition has been Marfrig’s meatpacking facilities. Minerva is buying beef slaughtering capacity in Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina for 13 thousand heads, increasing capacity by 44% at the company level.

Further, after the acquisitions, it will control 50% of Uruguay’s export meatpacking market and close to 40% of the Brazilian market.

I believe that Minerva has done great business with the acquisitions (still pending approval from the competition authorities in Uruguay and Brazil) and that Marfrig did the sale under distressed conditions.

Marfrig presented the sale as an optimization, abandoning the meatpacking business to focus on beef industrialization. However, Marfrig is much more leveraged than Minerva, with net Debt over EBITDA of close to 7x, versus Minerva’s 3x. While Marfrig’s operating income minus interest expenses is close to a negative $1 billion, Minerva is generating $250 million. Marfrig’s net interest expense represents 65% of the company’s CFO versus 25% for Minerva.

According to Minerva, Marfrig’s assets should generate R$15 billion in sales. This means, potentially, using the company's 8/9% margins, R$1.3 billion in operating income. This implies a P/S of 0.5x (compared to Marfrig’s asset turnover of 1x) and a P/EBIT of 6x.

Large shareholders and management

Minerva has two large shareholders that control more than 50% of the stock.

The founding family (Vilela de Queiroz) retains 22% of the shares. SALIC, a Saudi sovereign fund company with operations and investments in food supply chains, bought 20% of Minerva in 2016 and increased to 30% in the 2020 financing round. The Chairman is an independent, but each VDQ and SELIC controls a Vice-Chairman and a total of five nonindependent directors.

Management is composed of long-standing members.

The company’s CEO is also a VDQ family member. He has conducted the company since 2007 and has been a C-suite in it since 1992. Before that, he worked for Cargill, one of the mythical trading houses of ‘World for Sale.’

The supply officer has worked with the founding family since 1978 and in the company since 2000. COO since 1999. CFO since 2010.

I have not found related party transactions at the consolidated level, and the company’s management and Board (22 members) remuneration was $10 million.

Foreign exchange accounting

Minerva is a leveraged company, 75% of its assets are debt-financed. The company posted negative net income for many years and only small earnings recently because of its significant financial expenses. It had to recapitalize in 2018 and 2020.

However, I believe the treatment of those financial losses has been correct from an accounting point of view but incorrect (or not complete) from an economic point of view. This has led to reporting depressed net income compared to the company’s future potential.

Minerva’s debt is 50% denominated in dollars. Those figures were a little higher going back in time. The company reports its financials in Brazilian reals. The Brazilian real (BRL) depreciated substantially in the past decade, from $0.65 per BRL in 2012 to $0.2 per BRL in 2020.

Accounting rules indicate that foreign currency-denominated financial assets and liabilities must be adjusted when the exchange rate moves. This adjustment can be carried in the income statement or other comprehensive income. Minerva decided to report the adjustments in the income statement as part of the financial expenses, mixed with interest payments. Because Minerva was highly leveraged, and the BRL depreciated 300%, these USD debt to BRL losses were significant.

However, there are some problems with this reporting:

It reports all the changes in the debt principal’s value (in reporting currency) in a single period. In contrast, the principal is normally not considered an expense (only a movement), and costs are generally amortized.

Non-financial assets like PP&E, intangibles, or inventory probably also move with exchange rates, but these are not adjusted.

The effect is that the same company in Brazil, but using the USD as its functional currency, would have shown consistently higher net income. The problem is compounded faster when financial databases translate those BRL expenses into USD when they shouldn’t exist in USD accounting.

Indeed, a depreciation of BRL can put financial strains on a leveraged company as long as its operational earnings capacity, measured in USD, is also affected. However, interest service and repayment capacity are unaffected if the company’s operations do not ‘depreciate’ with the BRL.

The difference is noticeable when we move to cash flow accounting:

Minerva’s net income was consistently negative between 2012 and 2018, with losses reaching $500 million at some points. Since 2018, it has reached a local maximum profitability of $150 million.

Compare that to CFO minus interest expenses (we must remove them because Minerva reports cash interest expense in financing income). These losses only reached $200 million negative, have been positive since 2018, and have averaged $270 million, again since 2018.

Was the recapitalization necessary?

Indeed, Minerva was very leveraged before recapitalization in 2018 because it had taken debt for expansions. The company could not pay interest expenses with operating income, which showed up in its cash accounting losses before 2018. This could have, on its own, led to the recapitalization.

However, the treatment of USD-denominated debts exaggerated those losses without a cash correlation. Because the losses showed up on equity, eventually, the company showed an equity deficit. This would have complicated financing, and I believe the recapitalization successfully solved this problem.

The founding family and the Saudi sovereign fund, the two largest shareholders, kept their stake in the company by subscribing to the equity raises.

Today, the company is in a different position. It can generate net income even considering the BRL adjustments, and much larger if those adjustments are removed.

The issue of cash

Historically, Minerva has accumulated a lot of cash. Since 2012, cash has averaged 37% of Minerva’s assets. This seems strange to me, and I have not found an answer for such a high cash holding except as some form of covert working capital.

To begin with, the company did not invest most of that cash in interest-bearing deposits until very recently. It could have offset a substantial portion of its interest payments but decided not to. This, to me, has to have a motive.

Maybe the company needs all that cash for working capital purposes, but this should have shown some volatility in other working capital accounts. Some quarters should show cash decreasing and inventory or receivables building up. But that is not the case either. Receivables and inventory make up less than $1 billion, against $1 billion in cash (before receiving financing for Marfrig).

The only explanation I can find is that the company turns over its receivables and inventory so fast (averaging more than 15x in both accounts), that it can record that cash consistently as cash and not as working capital every quarter. But even this seems difficult to do.

Maybe the company wanted to have dry powder for a potential acquisition like Marfrig, but in that case, why didn’t they invest the cash in short-term interest-bearing deposits, and why do they plan to finance Marfrig’s acquisition with debt?

I believe that conservatively, the $1 billion in cash has to be considered working capital and not potential repayment for debt.

Napkin model and valuation

Minerva has been very consistent in terms of operating margins and ROCE.

I expect this trend to continue and strengthen in the future. The company has temporarily guided for lower operating margins (maybe in the realm of 7 to 8%) as the acquisitions from Marfrig are integrated. It could take as much as 2025 or 2026 for the margins to return to their mean.

The after-acquisition entity could generate $9 billion in revenues or $680 million in operating income if an 8% margin is applied. This is considering no further improvement in the company’s competitive position. I believe the new assets will increase the company’s bargaining power with ranchers and clients. Its cycle-average margins should climb further.

The issue of leverage is complex. Management has guided for a net debt to EBITDA ratio of 2.5x, 18 months after the acquisitions are completed. With EBITDA margins of 9%, this would mean close to $2 billion in net debt. However, net debt is not a great measure of total indebtedness because the company holds a lot of cash for working capital purposes. If we follow my speculation that the $1 billion in cash has to be kept for working capital, then the actual debt should be around $3 billion at maturity.

The company was able to finance at 8.9% in September 2023, and we can use this interest rate as a relatively conservative measure for two reasons. First, the company could reduce leverage if rates are this high, given that those rates are close to or above ROCE, removing value from equity. Second, Brazilian CDI and Selic rates are decreasing as the country has reduced inflation to 3%, but rates remain above 10%. Approximately half of Minerva’s debt is tied to Brazilian rates.

Using that 9% over $3 billion, we arrive at $270 million in yearly interest expenses. We are not offsetting any interest income from the cash holdings, netting any cash to debts, and using a higher average interest rate than what’s effective today (6.5%).

Still, we could be talking of $400 million in pre-tax income after paying for interest if the Marfrig acquisitions are approved and using the company’s margin projections.

Finally, we could remove 35% of income taxes using Brazil’s rate. This would be conservative, but Minerva has substantial deferred tax assets from the losses generated from the debt revaluation (which are valid in Brazil’s BRL income statements). This means that the company’s effective cash tax rate will be lower.

Even then, we arrive at $260 million in net income, compared with a market cap of less than $1 billion.

If the acquisition doesn’t happen and the company does not leverage further, we are talking of $400 million of current operating income (in cyclical low margins of 7.5% today) , and 9% interest on $2 billion in debts (assuming rollover at latest rates), or $180 million. That leaves $220 million pre-tax and $143 million after 35% tax without deferred assets. Again, against $1 billion market cap.

A great 👍 article!!!

what is current situation withe the Minerva and its valuation?