This article reviews the Brazilian Education industry, its segments, economics, and the stocks accessible from the US.

Education is a segment with very interesting economics: the potential to build reputation, high pricing power, barriers to entry, and customers that see the product as highly aspirational. In addition, Brazil has a large private education sector covering 80% of higher education and 20% of K-12 students. The market is massive, with 50 million K-12 and 9 million higher education students. The local stock market has nine public companies, three of which are accessible from the US (AFYA, VSTA, and COGNY).

The above positive conditions led to an explosion of investment in the 2010s and post-pandemic period. Now, the companies are heavily leveraged after the investment and roll-up spree, and their stocks are at all-time lows in most cases. However, their returns on incremental capital are more attractive than the accounting reveals (thanks to dampening from goodwill). This could represent an opportunity in principle.

Unfortunately, when we cover the three main segments of the market (higher ed, medical education, and K-12 teaching systems), we will find that oversupply is probably leading to higher competition in the near future. This leads me to believe that returns will not be as attractive. The only exception is K-12 teaching systems, which leads me to pick Vasta Platform (VSTA) as the company with the best long-term perspectives in this market (although I do not think its current stock price is opportunistic).

As always, if you liked this article, please help me share it, and if it’s the first time you are reading, be sure to subscribe to receive more industry and company analyses like this for free!

Others articles about Brazil

Or find all articles by category in the Index.

Index

Main segments introduction

Returns and history of public companies in the industry

Potential undervaluation?

Commoditized higher education: the uniesquinas

Medical education: supply tsunami ahead

K-12 teaching systems: interesting economics

1. Main segments

The education market in Brazil is divided into six main segments. This is a short introduction, and in later sections, we will explore higher Education, Medical Education, and K-12 systems in depth.

Higher Education

The largest by far, with 7 out of the 9 companies operating in this area. There are 9 million students, 80% of which go to private universities, and the number of students enrolled is growing fast. However, I believe this segment will suffer from oversupply, as the products are generally of low quality, and barriers to entry (like on-ground education) have been removed.

Companies: Cogna, Yduqs, Cruzeiro do Sul, Anima, Ser Educacional, Vitru.

Medical Education

This subsegment of higher ed is the most coveted by higher education companies, given its aspirational characteristics and super-high tickets. Monthly tuition for private medical education is above BRL 8 thousand, compared to less than BRL 500 for a distance education degree. The problem with this segment is that it is becoming extremely saturated.

Companies: Afya is the leader by far. Most of the higher-ed companies have some investment in medical, too, especially Cogna, Yduqs, and Anima.

K-12 Teaching Systems

Most K-12 schools in Brazil are public (80%), but the private segment attracts the aspirational investment of middle-class parents. The K-12 teaching systems sell pedagogical materials to the fragmented private school market. This segment is very concentrated, has potentially good economics, and is the one I find the most attractive.

Companies: Vasta (and Cogna indirectly as owner of Vasta), Arco (which was taken private last year).

K-12 Schools

The super-fragmented 20% of private K-12 schools is increasingly becoming a target of roll-up plays. Because managing these schools is complex, the scope of the roll-ups is currently concentrated on the premium segments (bilingual and international schools).

Companies: Bahema is the only public player, with Cruzeiro and Vasta having small operations. Previously, Cogna also participated but sold its schools in 2021. Large private players include Grupo Salta (ex-Eleva) or Inspira.

Vestibular (or university courses)

To access the more prestigious public university system, students need to pass a national ranking exam and sometimes also a school-specific course (the vestibular). Many companies offer courses and books to prepare for these exams.

Companies: There are no pure plays, but Vasta is a leader, and most of the higher education players also participate.

Ed-tech

Hundreds of ed-tech solutions exist for complementary studies, school administration, marketing, etc. Because of the fragmented nature of the market, there are no public players, but each public company has a dozen ed-tech products.

2. Returns and history

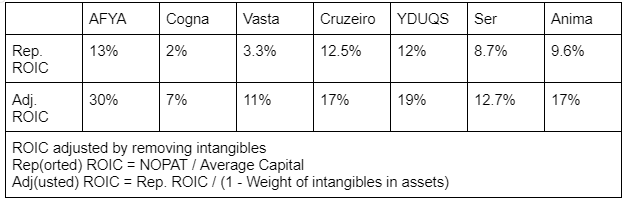

The Brazilian education sector is growing and profitable. However, the return on capital and valuations do not reflect this. Most of these companies overleveraged in acquisition sprees before the pandemic. The businesses have high returns on tangible capital, but this does not show up in accounting because of intangibles. Further, with high interest rates, Brazil is not a nice country to be overleveraged.

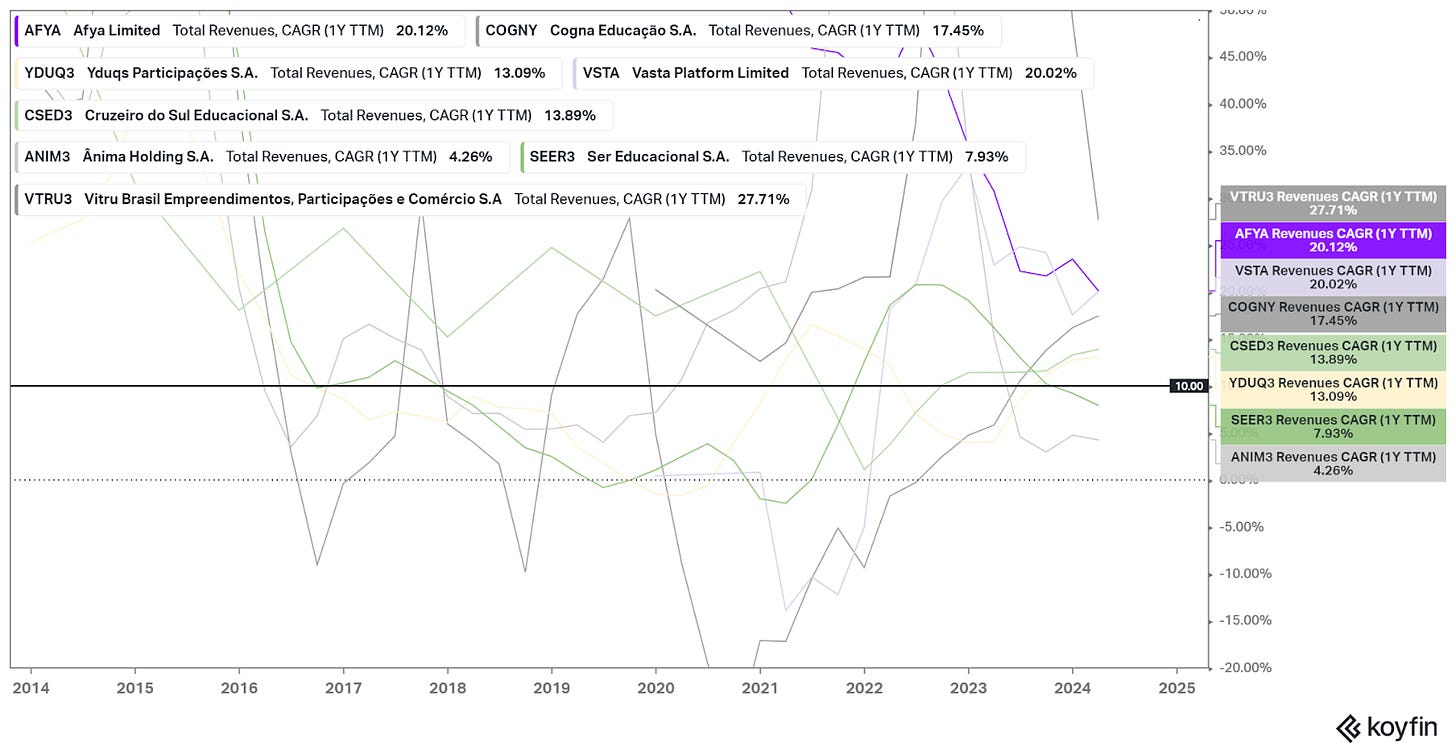

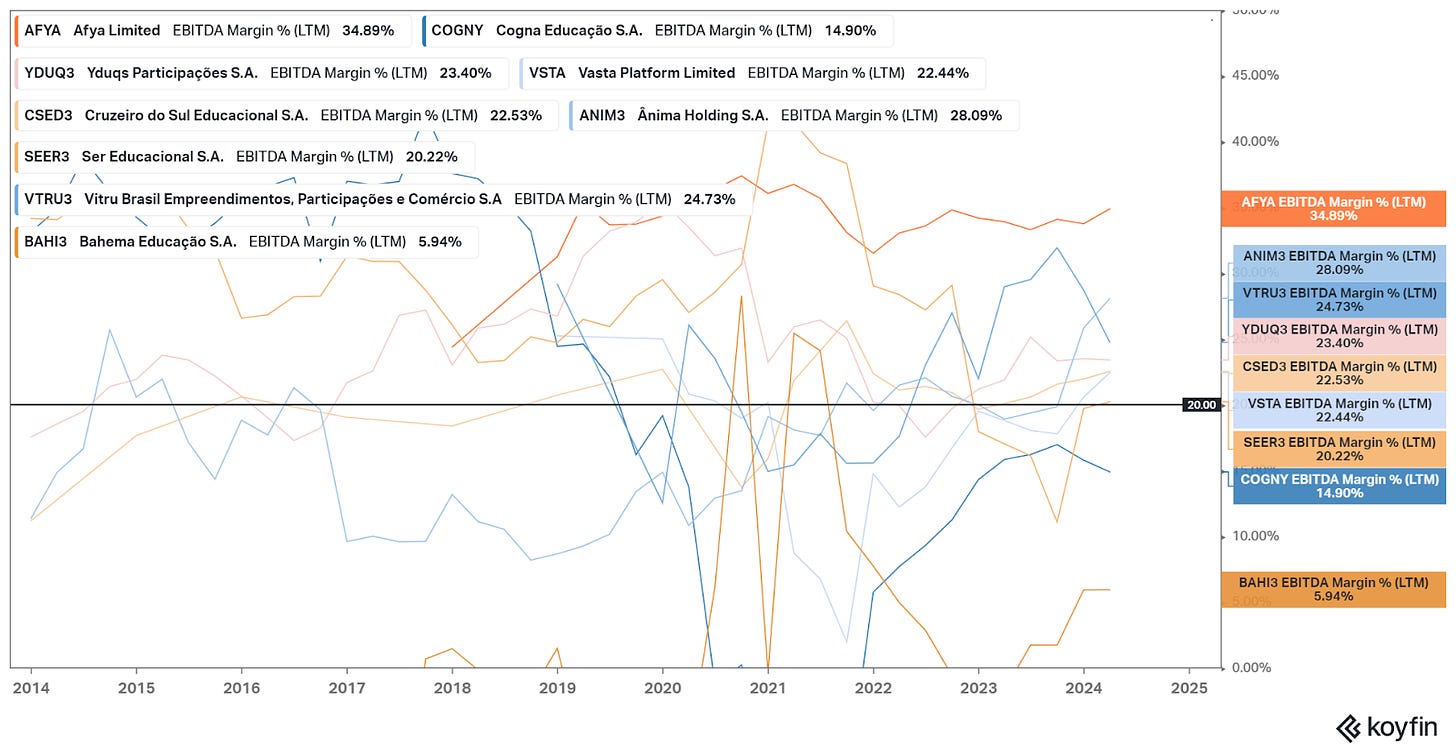

High growth and margins: We can observe below that most companies in the market post 20% EBITDA margins and are still growing above 10% rates. This seems like an attractive sector.

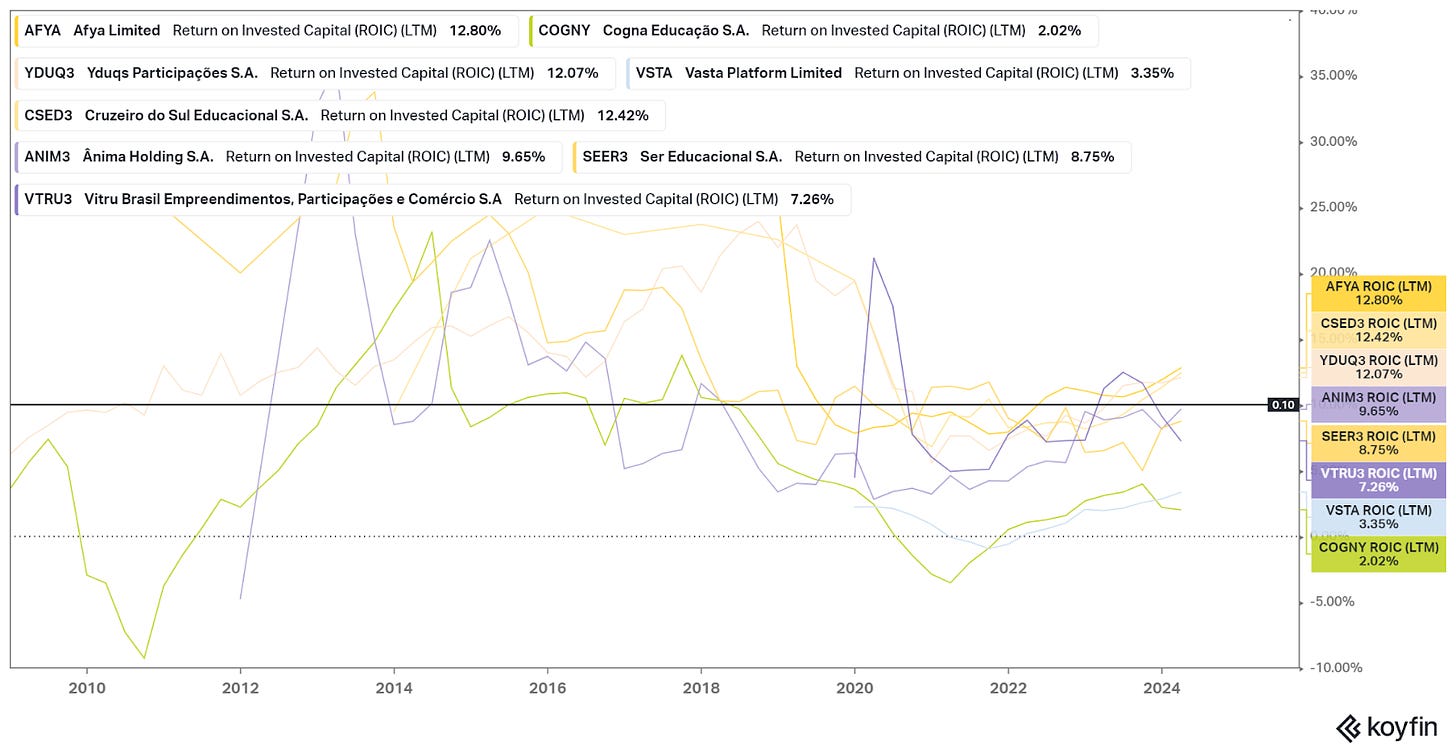

But low returns: However, returns on capital are not that good, generally below 10%. The majority of these stocks have negative ROEs. Why is this?

The effect of intangibles on ROIC: Roll-up plays flooded the attractive education market during the 2010s. These companies grew by acquisition. When a high return on capital business gets acquired, it is very probable that the acquirer will register a lot of goodwill. This, in turn, reduces the acquirer's return on capital.

Intangibles and goodwill make up 35/40% of assets for YDUQS, Ser, and Cruzeiro. For Afya, Cogna, Vasta, and Anyma, intangibles are 60/75% of assets. After adjusting ROIC by removing intangibles, the company’s ROICs are much better.

Super levered: Unfortunately, most education stocks levered significantly in the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods, financing their acquisition sprees. This has led to most companies posting super high leverage ratios even today. Add the fact that Brazilian interest rates are high (13% last year, expected an average of 9% this year), and the education companies are pressured below the EBIT line.

3. Potential undervaluation? Segment dependent

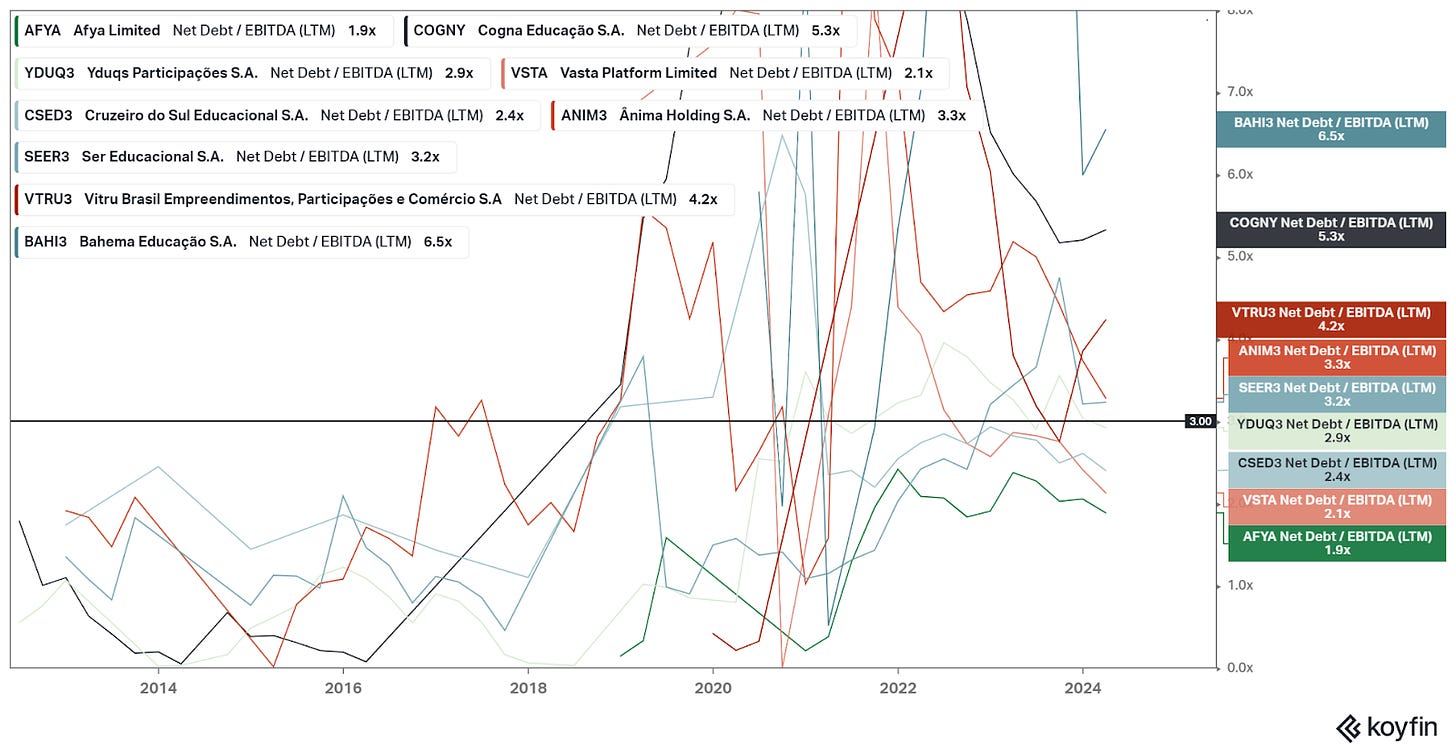

If a company can reinvest capital at X rate in the future, and we assume that management will maximize the returns from debt (i.e., maintain debt only if it yields well below ROIC and repay otherwise), then the stock’s returns should approximate or exceed ROIC / P/B over time.

However, when we look at the education stocks, many are trading below book value, and most do not reflect their adjusted ROIC. This leads me to believe there is a potential undervaluation: the companies’ markets are attractive, but their equity is undervalued because of leverage; as these companies deleverage and their cash flows reflect their lower capital requirements, the equity could reprice upwards.

More simplified: these companies don’t need much capital and operate in profitable markets, which allows them to deleverage. Both the returns on capital and the deleverage will increase the equity value.

However, when taking a closer look at these companies' markets (particularly higher education and medical education), they do not seem as good in the future as they were in the past. These markets seem oversupplied with little differentiation. Adding high fixed costs and leverage, companies have incentives to engage in price competition, destroying profits.

On the other hand, the K-12 systems market seems much more interesting, which leads me to pick Vasta Platform in this sector.

4. Commoditized higher education: the uniesquinas

In the higher education segment, I have found serious indications of an extreme oversupply of low-quality universities offering mostly undifferentiated online courses. These courses have fixed costs (platform, teachers, admin) and don’t have physical limits like normal schools. Therefore, universities are incentivized to lower prices and drive volumes, destroying profitability.

Distance and private higher education

Brazil has about 9 million higher education students, and 80% of them go to private universities. Public universities, which are the most prestigious, have stringent admission requirements and low capacity.

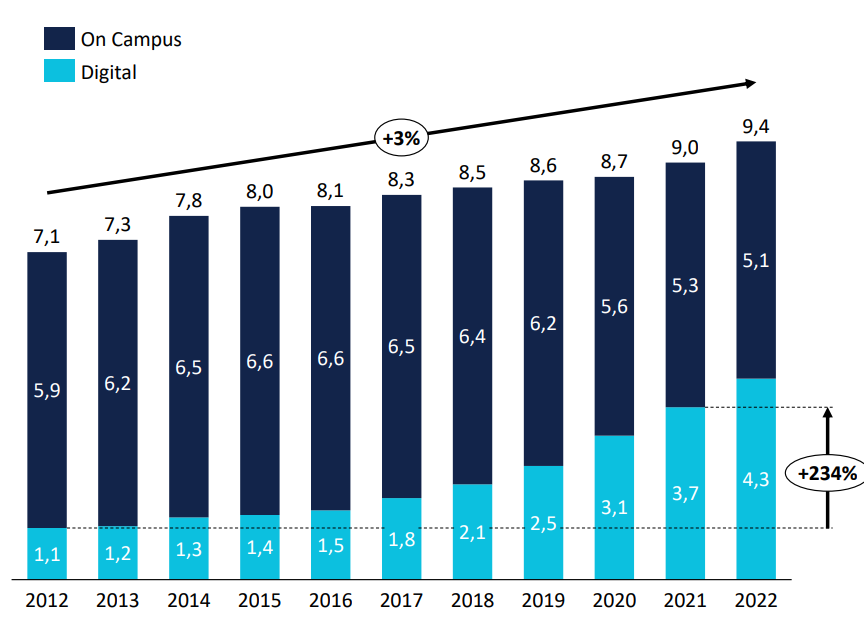

Almost 50% of those students are distance learning students. Further, as seen below, the distance education market is growing fast, whereas on-campus education is shrinking, especially after the pandemic.

Distance education has the advantage of being way cheaper than on-campus. Monthly tuition for an online degree can range between BRL 200 and 350, whereas it climbs to BRL 1 to 1.5 thousand for on-ground courses.

Low-quality uniesquinas

The Brazilian private higher education market is highly fragmented. There are nearly 3,000 schools, and almost half have less than 500 students.

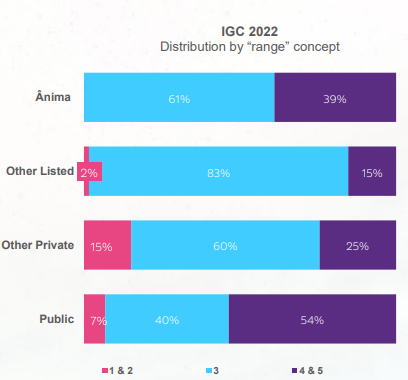

The quality of these institutions is low. The Ministry of Education releases a General Course Index (IGC) that qualifies schools from 1 to 5. A level of 3 is the minimum satisfactory score to have the school license renewed, and schools get a ‘3’ even if their score is 2.1. Below are the rankings of schools by segment. Most private schools have the lowest permissible ranking, and the situation is even worse in listed private conglomerates. This has led to the coining of the term ‘uniesquina’ or ‘corner university,’ meaning a university built on a busy corner in town, resembling a night school more than a college.

Oversupply is evident

Technically, schools can only offer a limited number of seats per course, even for online degrees, and they can only offer them regions around their campuses. However, schools can set up ‘education hubs’ or ‘digital learning points’ to expand capacity. These hubs are no larger than a store with a few offices and provide students with some administrative endpoint. This means there are no barriers to entry in this market.

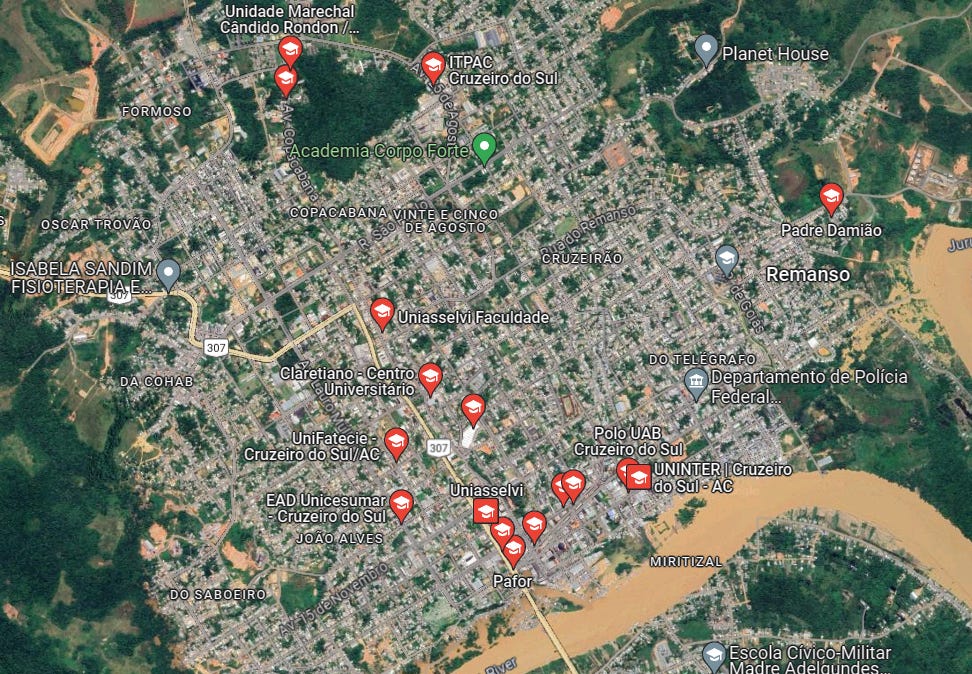

You can check the level of oversupply easily with Google Maps by visiting any small town, even in the remotest areas of Brazil, and looking for the keywords ‘universidade’ or ‘faculdade’. Chances are, even in a small town, you will find a dozen uniesquinas. The pictures in Google Maps easily evidence the quality of the institutions.

Below is Cruzeiro do Sul, a town of 92 thousand people in Acre, quite literally in the middle of the Amazonas forest. It has more than 10 ‘universities’.

The economics are negative over the long term.

The economics of a low barrier to entry, high fixed cost percentage, and fragmented and leveraged market are terrible over the long term. Schools have an incentive to drive volumes up to dilute costs, but this leads to the destruction of profitability.

Schools can post growth for some time as they increase the number of hubs they have and can expand geographically with low capital, but this has a limit. Each of the listed companies has a thousand or more ‘learning hubs,’ but Brazil has less than 500 cities with more than 50 thousand inhabitants.

This leads me to believe that, in general, this market will be more challenging in the future and that diving deeper for opportunities here is not a super fruitful idea. It could be that some of the players are better positioned, but given most of the stocks only trade in Brazil and have no American ADR, I believe it is better to move on.

5. Medical education: potential capacity tsunami ahead

Medical education is the crown jewel of the higher education market. All listed companies boast their expansion into this segment because of its great economics. However, the degree of supply expansion has reached a limit that will probably convert the whole medical profession into an overcrowded activity in a few years. The effects of this on the schools are uncertain, but the dynamics are not positive.

Better economics

Medical schooling is much more profitable. For example, Afya, solely focused on this segment, posts 30% EBITDA margins and the highest adjusted ROIC among the listed players.

Schools cannot offer online medical degrees (although they have tried), and the Ministry of Education has to pre-approve courses, so there are some barriers to entry. Further, doctors make a good living in Brazil (100% employment, among highest paid professions), and it is a prestigious and aspirational career, so tuition is extremely expensive. Tuitions can start at BRL 8 thousand per month and go as high as 12 thousand per month. Compare that to BRL 200 hundred for an online degree.

Further, Brazil has had an undersupply of doctors. Brazil still posts an average of less than 3 doctors per thousand inhabitants, compared to 3.4 for the OECD. The disparity is more pronounced between the rich southern urban regions (4 in SP, RJ, or RS) compared to the poorer Northeast and interior (less than 1.5 in PA, AP, and MA).

Capacity explosion

An aspirational, expensive, and undersupplied market seems like an investor’s dream, but it has been overdone. Today’s capacity is ten times higher than required to maintain a normal ratio of doctors. This will probably lead to the profession’s value decreasing over time.

Brazil’s latest doctor’s ratio was 2.8, or already pretty close to the OECD average of 3.4. Its population is expanding at a rate of 0.5% per year, or about 1 million people. This means that to maintain or slightly increase its ratio, Brazil should graduate about 3.5 to 4 thousand doctors per year (considering people that retire). However, Brazil graduated 35 thousand doctors last year and is expected to graduate 40 thousand per year by 2030. The government plans to open 10 thousand more seats in the next few years, fueling the problem.

The math is simple: if you are graduating 35 thousand doctors, you only need 4 thousand to maintain a healthy ratio, and your population is 200 million, then the ratio will grow at a rate of 0.15 per year. In less than ten years, Brazil will have a ratio of 4.5 doctors per 1,000 people, one of the highest in the world.

Economics of doctor oversupply

We can know with certainty that the ratio of doctors in Brazill will increase rapidly in the next decade. However, the impact on the schools will have a lag effect and is not very certain. It is unclear that doctors will become overabundant and dispensable just because the ratio is above a certain level.

For example, despite most states having less than a ratio of 3, if we only consider state capitals, most states are above 4, and more than half are above 7. So, the capital cities can hold higher ratios without affecting employment or salaries. However, this is probably because the capitals also receive demand from neighboring areas, and doctors want to live there. Not all small towns can have all specializations, leading to a skew in the capitals and large cities.

Even if medicine becomes an overcrowded activity, it will take some time for the impact on salaries and occupations to be felt, and some more time will be needed until prospective students start thinking of alternatives. Currently, employment is close to 100%, and median salaries are about BRL 16 thousand, compared to BRL 2 or 3 thousand for the country’s median. The median salaries for young professionals (less than 30 years) have not decreased.

The position of Afya

Afya owns nearly 6% of the market, with 2.5 thousand seats out of the 43.5 thousand available in the country. It is the largest player. The company expects to reach approximately 4 thousand seats by 2030.

Although I believe the oversupply of doctors will take time to hit the market, I do not believe Afya has a defensible position.

Quality risks: Like most listed higher education companies, its schools are not prestigious, with an average IGC of 3.26, compared to the country’s average of 3.18. Criticism is relatively extended in specialized forums like r/MedicinaBrasil, or even in the comment section of any of their schools on Google. Some of the complaints are that the Afya schools (or Anima’s schools, to name a competitor as well) do not require a pre-course (a vestibular). They basically accept anyone who will pay for the course. Others criticize Afya's decision to remove the best-paid teachers and hire less experienced doctors after acquiring a school.

Of course, availability bias is a problem here. Afya has 20 thousand students, so some will always complain. However, I believe this puts Afya in a bad position with two risks. One is that if there is an oversupply of doctors, the first to feel that are going to be the less prestigious (and probably the worst educated) doctors. This can lead to a ‘I went to Afya, and now I cannot get a job’ type of situation. The second is that the quality is so low that wrongdoing cases start surfacing, and a general wave of societal criticism against private schools leads to closures.

Northern regions are relatively oversupplied: Afya’s schools are mostly located in the northern and northeast regions of the country. These are the States where the doctor population is lower, but also where working conditions are worst, and population density may not allow high ratios.

200A useful statistic for an oversupply of medical seats is medical seats per 100 thousand people. The OECD average is 17, and Brazil’s average is 22.5. Some of the States where Afya operates are well above this: Tocantis, where Afya has 320 seats, has a ratio of 55; Rondonia (200 Afya seats, ratio of 44); Acre (50 Afya seats, ratio of 30). Others are not: Para (390 Afya seats, ratio of 14); Amazonas (100 Afya seats, ratio of 17).

Specialization graduate path: If the doctor profession ends up oversupplied, then becoming a specialist becomes important. There are two paths to becoming a specialist in Brazil: residency and specialization courses. Residency is preferred because it requires thousands of hours of hospital practice. The problem is that it requires ranking on a very competitive national exam. Schools cannot generally offer this path because they would need to operate hospitals. The second path is called specialization or post-graduation. Only the theory is taught, with little practice, but the student needs to pass an exam at the end before being able to work as a specialist in a hospital. The problem is that although both create a ‘specialist,’ only residency carries the necessary prestige to guarantee better employment.

Afya has 4.5 thousand post-graduation students and plans to extend the courses using the colleges it has as bases. The monthly tuition for specialist courses is much lower than for undergraduate doctors (BRL 2.5 thousand vs. 8 thousand) but still way above other types of higher education. This could be a potential way out of Afya's oversupply problem.

Conclusions on Afya

Afya is the most profitable player in the industry and is a pure play in the most desirable subsegment of higher education. The company is not as leveraged, and cash flows should allow it to reduce debt in the future. This would make it an interesting consideration for long-term investment at an EV/NOPAT for FY24 of 11x, with growth potential from maturing schools, tuition increases, etc. However, the extreme level of oversupply in medical seats makes me worry. I cannot predict what will happen with doctor salaries and the desirability of medical education when doctor numbers increase, but there must be an effect if the doctor population keeps growing 10x faster than the Brazilian population.

6. K-12 teaching systems: interesting economics

Brazil has nearly 50 million K-12 students, or almost 25% of its population, 80% of which go to public schools. However, private schooling is an aspirational goal of the middle classes. Going to a private school helps a lot in getting to prestigious public universities. The fragmented private school market is served by teaching systems that provide coursebooks, pedagogical materials, and increasingly help in other educational functions. This is particularly true in middle and high school before taking the university ranking exams.

The economics of an established system with a good reputation are interesting, with leverage of intangibles and relatively sticky customers. The market for these systems is mostly settled between a few big players, and channel checks lead me to believe that competition is not very fierce. These providers can expand by acting as gatekeepers and liaisons between ed-tech products and the schools. Further, they can expand systems to younger cohorts, like primary school.

Among these systems, the only public player is Vasta Platforms, listed in the US (VSTA). I believe this company is the most attractive in the Brazilian education market.

K-12 figures

Brazil has 50 million K-12 students, or 25% of its population (indeed a young country). This alone makes the segment interesting. The public, free system serves 80% of this population very poorly. PISA tests show that only about 20% of students have adequate competencies in most areas (figures that climb to 60% in private education). The picture inverts in college, with 20% of students accessing the prestigious public university system. Going to a good college is a ticket to the upper middle class and above. Therefore, going to a private school is an aspirational middle-class goal.

The private K-12 school market is highly fragmented, with 45 thousand schools, most of which have less than 200 students and are family-run. This market is difficult to consolidate because each school generates little revenue, and the largest, most prestigious school systems are not for sale (for example, because they are catholic schools).

The market has three segments: the low-cost and mass market from BRL 1 thousand to 2.5 thousand; the performance segment from BRL 2 thousand to 3.5 thousand; and the premium starting at BRL 3.5 thousand and above.

Great economics of a teaching system

In this arena of many small schools, teaching systems provide a leverageable service that improves student outcomes and helps the schools brand themselves at little cost to the school. 70% of private schools buy some type of teaching system. Combined with an amicable, concentrated market and leverageable costs, this makes for great economics.

Economies of scale: The systems exist because there are great economies of scale in preparing the books and class curriculum. On one hand, the schools cannot justify the cost of developing an in-house system. The systems are a one-stop solution to solve the curriculum, allowing school managers to focus on other topics and teachers to just provide the classes. On the other hand, the systems' variable costs are royalties to content writers, printing costs, and customer service consultants. The content is produced once (plus yearly renewals and a plethora of customizations) but can be sold to as many schools as needed. The cost structure is, therefore, pretty leverageable.

Systems have brand power: Schools can gain much branding power if they choose reputable systems, especially during middle and high school, before students take university exams. The brand power of these systems is high because they are well-known for their quality, and they help get students into the most prestigious universities.

Schools pick but don’t pay: The systems tend to cost between BRL 750 and 1,000 per student per year, representing less than 10% of yearly tuition. However, schools choose the system but don’t pay for it. Parents must buy the books, therefore financing the rest of the services, like pedagogical consulting for the school. The economics of this are great because the parents think: ‘I have to pay between BRL 15 and 30 thousand per year for school, I might as well get the best system for an additional 1 thousand’.

Oligopolic market: The two biggest players (Vasta and Arco) dominate 50% of the market via several brands. The remaining 25% is divided between three companies and another 25% among more than 40. This leads to a stable market with good economics. Channel checks confirm that the leading players are not interested in price competition.

Growth despite saturation: The majority of private schools already buy a system. The ones that don’t probably do not for a reason, like having their own system (more common in the premium segments). However, there are ways to expand each company’s market without engaging in profit-destroying competition. Some avenues include serving the public system via auctions (probably way less profitable per unit, but more massive and still leverageable), expanding in the less penetrated primary school market, and partnering/acquiring ed-tech companies that offer complementary services to schools (like ERPs).

Vasta Platform (VSTA)

Despite being the most attractive, there is only one public company in the K-12 teaching systems market, Vasta Platform, the country's second to first player. Up to 2023, the largest player, Arco, was also public but was taken private.

I believe Vasta enjoys the economics described above, owns some of the most reputed systems, and has an efficient structure. Although past capital allocation decisions were terrible, over-leveraging to overpay for acquisitions, like most Brazilian education companies, the situation is now better.

Vasta faces financing and controlling shareholder risk, but I believe it could become interesting at lower prices.

Basics and history: Vasta owns ten teaching systems that account for about 20% or 25 % of the Brazilian market, or 5,000 schools with 1.5 million students. The company was originally named Somos Educacao (and the OpCo is still Somos) but was acquired by Cogna in 2019. Cogna later spun off 20% of Vasta in 2020.

Great and good brands: Vasta owns some of the best-branded systems. Its top brand is Anglo, representing 25% of its students. Anglo is considered top 3 in the country, especially because of its high university acceptance rates. Many students who don’t attend Anglo schools buy books to prepare for university exams themselves or attend after-school Anglo programs. Other important brands include Eleva (now Amplia), pH, Maxi, and Etico. Each has more than 150 thousand students. 65% of Vasta’s revenues come from these systems, plus another 8% from sales of standalone textbooks.

Cost leverage: Vasta is showing interesting levels of leverage. Its gross margins have been growing since public information is available. SG&A is also showing leverage after the pandemic. One indication of the efficient cost structure of the company is that it has 2 thousand employees to handle 5 thousand schools. Employees account for 20% of the costs, similar to publishing and D&A. Further, with D&A representing BRL 300 million a year against CAPEX of less than BRL 150 million in each of 2021, 2022, and 2023, the company’s accounting EBIT margin will continue to expand simply from intangible depreciation.

Expansion avenues: The company can expand profits via margin leverage and the general increase of system prices over time, as is normal in education. It is also trying to expand via complementary courses (for example, on arts or STEM) and via sales to the public sector (specifically pointing to improving PISA and university test scores). Vasta also partnered with a K-12 school operator to offer bilingual schools with the Anglo system (called Start Schools).

Falling enrollment: One of the company's main negatives has been falling enrollment for two years already. In the 2022 cycle, enrollment peaked at 1.58 million, which is expected to fall to 1.45 million in the 2024 cycle. This is not a tremendous decrease, but it is a warning sign, given that private school enrollment continued to grow in 2023.

Bad capital allocation: Like most education companies in Brazil, Vasta overpaid for acquisitions. Vasta itself was overpaid for. It was acquired for BRL 1.5 billion in 2015 by a PE group, only to be sold for close to BRL 5 billion to Cogna in 2019, and now being worth BRL 1.4 billion. In 2021, the company spent BRL 600 million on Eleva, paying 20x EBITDA (using my own calculations). It bough the SESI system also in 2021, at 4x revenues (or 20x EBITDA using the same margins). Another example is the purchase of MindMakers in 2020 for BRL 24 million, with BRL 5 million in earnouts, only to increase earnouts in 2023 to BRL 33 million, or double the price.

Vasta has not engaged in large acquisitions since the market dynamic across education changed from growth to deleveraging and profitability. It bought a stake in an ed-tech in 2022 for BRL 95 million and a small JV in 2023 for BRL 5 million.

Not super-levered but risky: Fortunately, this has not led to a super-levered company. Total debt (including payments to sellers from acquisitions) amounted to BRL 1.2 billion, or 20% of capital. Still, when we add reverse factoring agreements (BRL 300 million) and tax liabilities (BRL 600 million), the numbers grow to 40% of capital. Against these, it has close to BRL 350 million in cash and marketable securities and another BRL 1.1 billion in current assets (total current 20% of assets).

Some other points add to the risk. First, the company is insolvent if intangibles and goodwill are removed (they represent 120% of equity). Second, because interest was close to 13% in Brazil in 2023 and now hovers around 9/10%, the cost of debt is high. In 2023, Vasta accrued BRL 240 million in net interest or 14% of net debt. Third, some maturities are close, specifically BRL 600 million in acquisition receivables to be paid in the next three years.

Parent risks: Vasta is 80% owned by Cogna, the largest education player in Brazil (currently concentrated mostly on higher education). Cogna is also leveraged and is one of the main financers of Vasta (BRL 500 million in bonds maturing in 2029 issued in 1Q24). With competition in higher education increasing, I see a potential risk from Cogna needing to sell Vasta and putting pressure on the stock.

Current profitability: When removing one-time adjustments and equity participation losses, Vasta generated 150 million in BRL in EBIT in FY23 or a 10% EBIT margin. This is a great improvement from 6.5% EBIT in FY22. In addition, CAPEX and intangible investments were BRL 160 million lower than D&A in FY23, and the company is no longer doing large acquisitions. This adds up to nearly BRL 300 million in EBITDA - CAPEX, or an adjusted EBIT margin of 20%. From this, we must remove BRL 170 million in interest (BRL 1.7 billion net debt paying close to 10%) to reach BRL 130 million in pre-tax, and about BRL 90 million in cash-based net income (tax carryforwards are BRL 200 million so we can ignore them on the long-term).

Slow deleveraging: That FCF or cash net income is insufficient to serve debt fast enough to make a big difference. It would take too long unless the company keeps expanding margins or growth. I would not specifically count on it.

Valuation not super attractive: Vasta trades at an EV (adjusted for interest-paying tax debts) of BRL 3 billion and a market cap of BRL 1.4 billion. These represent earning yields on NOPAT and net income (adjusted for excess D&A) of 7% and 6.5%. Debt repayments potentially add up to 1% of yield per year. Margin expansion will not increase meaningfully from these yields, given that they are already based on an adjusted EBIT margin of 20%. This leaves a lot of weight on revenue growth to obtain an adequate return (say 15% minimum, considering the financing risks and the omnipresent depreciation of the BRL risk). Still, I like the business and think it is the best positioned in the sector for the long term. Would reconsider below BRL 1.1 billion or an ADR price of $2.5.

Conclusions

Although the Brazilian education market was originally very attractive, and even today, it allows most companies to generate interesting goodwill-adjusted returns on capital; overinvestment has mostly led to overcapacity and overleveraged companies.

This leads me to believe that the low valuations of most education companies are correct, as their future competitive environment will be more challenging than today’s. The only exception is the K-12 teaching system market, with Vasta as a leading player with good potential and more defensible economics. I don’t think the current price screams Buy, but it is still an interesting company to follow closely.

If you liked this article, help me share it! And if you haven’t yet, don’t forget to subscribe!

Insightful and well-researched article!