Footwear primer (and US companies)

Fallen angels, compounders, nosebleed growth, and deep value in the realm of shoes.

The footwear segment has a little bit for everyone: nosebleed growth, compounders, fallen angels, and roadkill deep value.

Many footwear companies are booming with new business. Brands like Hoka, On, Crocs, and Birkenstock are all growing spectacularly despite the supposedly challenging macro. At the same time, the segment also has value plays. Smaller businesses in manufacturing and retailing trade at what could be considered value prices because of the terrible 2022/23 destocking cycle. The giant Nike is guiding a negative FY25, leading to its stock more than halving since its peak and reaching valuations not seen since the GFC.

This primer covers the basics of the footwear market. As I have written a lot about the apparel sector, you can find a lot of general ideas that are also valid for footwear:

Apparel Intro: The main competitive dynamics of the industry like fragmentation, subjective focus, business models, and risks.

Apparel Retailers Primer: How retailers compete, why it’s different from manufacturing, specific challenges and pitfalls.

Apparel Brands Premier: Role of fashion in society, intangible management of the apparel brand, segmentation, and risks.

Apparel US Company Analysis: Short analysis of more than 30 US apparel retailers and manufacturers.

In this primer, however, I will go one step beyond and assess the specific dynamics of the footwear segments, what to look for and how to identify opportunities. This primer also has the analysis of most of the US companies in the footwear segment. I explain their models, how their business is doing, and whether their valuation presents opportunities.

If this is the first time you are reading, be sure to subscribe!

Also, make sure to visit the Index.

Let’s get started!

Footwear basics

A quick review from the apparel world

Footwear is the sister of apparel, a sector I have covered ad nauseam. Let’s recap the main ideas:

The first important concept to grasp is that footwear consists of two very different subsegments: brands (manufacturers) and retailers. Each has its own economics and managerial focus. Brands have better pricing power and focus on building intangibles. They are generally better businesses but can suffer from significant fashion risk. Retailers, on the other hand, are in a more competitive arena and focus on resource efficiency. The retailing business has a lower margin and is more difficult, but does not suffer as much from fashion risks.

Footwear brands (manufacturers)

Footwear manufacturers is a legacy term that refers to brands generally not involved in manufacturing. Nike, Birkenstock, Skechers, On, etc. are all ‘manufacturers,’ although none have factories (except for Birkenstock). That’s why I prefer the term footwear brands.

The brands' segment is generally much more profitable and scalable than the retailer segment because brands can create unique irreplicable intangible assets: the brands themselves and the footwear designs. Let me unpack this:

Think of buying a pair of regular flip-flops. You have a lot of options at your disposal, some more expensive, some cheaper. As a customer, you can get a really good appreciation of these different options' price/quality ratio simply by visiting a few stores and touching the products, or you can check a review video. Flip-flops, in this case, are a commodity.

In contrast, imagine you want a pair of tennis shoes. You go to the shop and find the a pair of Nike Air Force 1, the best selling shoe in the history of the world. This is not just a pair of shoes; it is a unique fashion piece that no other brand can copy. You cannot compare the quality with another brand because no one else makes this specific pair. This gives Nike a lot of pricing power. Most companies in the brand segment have gross margins of more than 60% or even 70%, meaning that the cost of making the shoes is negligible.

As an example, this pair is almost identical to the AF1, and retails for $18 at Walmart, versus $120 for the Nike pair. I haven’t touched the Walmart ones, but I’m almost sure that the quality difference is negligible. They may even come from the same factory. A simple logo added $100 to the price tag.

However, Nike did not receive this incredible advantage for free, and although it cannot be copied, it must be protected and nurtured. The Nike Swoosh logo is so valuable because it has accumulated some form of expressive power in the minds of millions of customers. On the one hand, you see a pair of tennis shoes, on the other one, you see the greatest athletes of all time, the best rap musicians, and the cool kids in the movies. This type of inexpressible qualitative factor is called the brand's cultural relevance. Brands are also tied to a fluid cultural space. For example, Nike is tied to sports, rap, and coolness, but also things like youth, power, speed, African American culture, or even the American dream. The position of the brand in this cultural space allows the wearer to express in society.

The number one job of footwear brands is to create and maintain cultural relevance, which in turn is tied to a cultural space. This requires managing intangible resources like designs, marketing, advertising, sponsorships, etc.

Finally, because of culture changes, brands suffer from fashion risk. Fashion risk means that people change what they like over time, and some shapes, colors, and concepts simply go out of fashion. When that happens, the sales of footwear brands can suffer a lot, really fast. The concepts that make their cultural space may not be important or valuable to society anymore, or the brand may stop being a vehicle to express those concepts. Not all brands suffer from fashion risk to the same degree though, some are tied to a cultural space that is more permanent, whereas others are pure fads.

Footwear retailers

The other segment is footwear retailers. Retailers generally do not own brands, but rather resell many brands. Until the advent of e-commerce, most footwear brands did not engage in retailing. Although now they increasingly do, even today most brands still derive most of their sales from selling to distributors and retailers (the wholesale channel).

Retailing is naturally a lower margin, less profitable and more competitive segment. This is because retailers work with replicable or commoditized supplies, and (from the customer's perspective) also sell commoditized (although branded) products.

The retailer's resources are store locations, fixtures, labor, shoes, warehouses, and advertising (or data center capacity for an e-commerce website). All of these resources can be acquired by competitors as well, and have a market-defined price.

From the customer's perspective, retailers’ products are also commoditized, even though they have a brand. True, the Nike Air Force 1 is unique, but the AF1 pair I can buy from Foot Locker is the same pair I can buy from Amazon or JD Sports. In addition, as a customer, I can check the price of the pair in all of these retailers with a few clicks. This puts a hard ceiling on the retailers’ pricing power.

Retailers can have a little brand, like being known for being the store with the most variety, or the most knowledgeable employees, or the cheapest prices, but this brand is not remotely as powerful as that of footwear brands.

Even though the retailing business is generally worse than that of brands, some retailers can do well. However, given the limitations they have on the resource and end market side, their focus has to be on efficiency:

The job of the retailer is to manage its commoditized resources as efficiently as possible. Sometimes, they can also create small irreplicable assets, like good processes (which lead to efficient use of resources), or access to specific niche demographics, but this is rarely the norm.

At the same time, retailers generally suffer much less from fashion cycle risk, unless they are very closely related to a particular style. Retailers can generally move with the currents of customer opinion and offer whatever is in demand at the time.

Differences between apparel and footwear

The world of footwear also has its differences with apparel, which become crucial when evaluating companies. The two main ones are that the branded market is much more important in footwear than in apparel (where the biggest companies are actually retailers), and that the market is heavily concentrated on specific athletic styles, compared to a much more broad offering in apparel.

The extra value of brands

Brands are extremely more valuable and ubiquitous in footwear. You can confirm this simply by looking at how big brand logos are displayed in most footwear compared to most apparel. The market for unbranded footwear is much smaller than that of unbranded apparel. Even the designs that do not have big logos tend to have identifiable attributes, like silhouettes.

This leads to retailers being in a much more challenging position. In apparel, you can find gigantic retailers like Zara, Uniqlo or Gap, that underplay the branding (and specially logo) aspects and focus on the supply-chain retailing aspects of the product. But this model is not nearly as successful in footwear.

The weight of function and the dominance of athletic footwear

The higher value of branded products in footwear comes from the much more important role that shoes play in our everyday lives, which leads to a focus on quality. Because quality is not always easy to grasp, as in the flip-flop example, brands have space to grow. For example, if you buy a cheap T-shirt it may itch a little or get damaged more quickly, but if you buy some cheap shoes, your wil get back and feet pain. That’s why most people, even of modest means, try to invest a little more on quality footwear.

The importance of the more functional aspect in footwear also explains why the biggest brands in the world of footwear mostly come from an athletic background, even though they may now serve a primarily lifestyle-oriented market. Athletic shoes like tennis, running or even basketball shoes are extremely more comfortable than the average dressing shoes. This has led to a gradual abandonment of the dressier forms, which have been in retreat for decades. Even outside of athletic shoes, the rest of the successful brands of the moment have very comfortable shoes (I’m thinking of UGG, Crocs and Birkenstock).

Finally, the focus on function and quality has led to an explosion in detailed footwear reviews. When researching footwear, specially functional footwear (say trail running shoes), you can find dozen review videos in Youtube, each with hundreds of thousands of views. Although the same exists in apparel, the level of detail the footwear reviewers reach is much more granular. In the long-term, this could have a big impact on the value of brands.

Analyzing the US footwear companies

How do these principles apply when evaluating the business models of different footwear companies? We will now review specific companies and how they built their models around the retailer/brand continuum. By analyzing their differences and similarities, we will also gain a better idea of how they might do in the future. The section also includes my opinion on the valuation of some of these companies as of this writing, but this is not as important as understanding the model, because valuations change very often. This section doesn’t contain some large players from abroad, specifically Puma, Adidas, and Asics, or private players from the US, like New Balance.

Large athletic

The athletic brands dominate the market. Although competition is high, all of these companies post high gross and operating margins and have grown without bumping into each other much. Because this is the creme of the market, their valuations are generally high, and they do not represent an opportunity except for the occasional dip. Even in that case, the multiples are elevated (ask Nike, 50% down and still trading at 22x earnings).

Nike, the hamstrung giant

One liner: Now that Nike’s model has problems, lots of people point fingers at the company, accusing it of not innovating. However, I think reaching the limits of a model is natural. Why would anyone change a model that is working until it stops working? Now that Nike is forced to change, it has all the resources needed to do it.

Nike is the largest footwear brand in the world and has been the leader for decades. The company created the concept of an athletic shoe that can be worn daily while pioneering and dominating performance markets like basketball and running. Nike literally created the shape of the shoes we see on the streets today.

However, today, Nike is highly challenged and has lost 50% of its market value since its peak in late 2021. Its sales are stagnant while competitors in performance and lifestyle advance at large strides.

Although the company is indeed facing many headwinds, I believe it will recover and that its core failures were, in large part, inevitable. We will first review the criticism and then the company’s strengths and my thesis.

What went wrong

Everybody can explain what happened once it happened, so now that Nike has lost half its market cap, the reasons abound, but here are the main ones:

Inexpert CEO: Nike’s current CEO (in office since 2020) comes from the world of technology, not footwear. He is blamed for the company’s current situation because he initiated a lot of change.

Division rearrangement: The company moved from a sports and brand based structure to a customer (men, women, kids) based arrangement. This led to several well publicized failures in quality and production, and general organizational chaos.

Wholesale channel abandonment: Most of the footwear brands don’t do retailing, and Nike is not the exception. Nike derives most of its volume (2/3 even today), from selling to distributors and retailers.

However, the company has a large DTC e-commerce operation, and part of its pre and post-pandemic strategy consisted of ditching its wholesalers in favor of online sales. In order to do this, Nike directly stopped working with many smaller distributors, and curtailed the inventory it sent to other large retailers (like Foot Locker for example).

Although this was considered genius during the pandemic, the strategy opened the gates for other brands (like Adidas, On Cloud or Hoka) to gain shelf space in the retailer stores where Nike was purposely shrinking inventories.

In my article about apparel brands, I specifically mention that brands should not put too much emphasis on retailing because their core competencies are not selling but managing intangibles.

Lack of innovation: The footwear experts, Youtube reviewers, and sneakerhead influencers all put the bulk of the blame on Nike’s lack of product innovation. The company did fantastically well until the post-pandemic by rehashing the same historic and legacy products like the Air Jordans and the Air Force. These products had been invented decades ago and were a hit, but Nike did not reinvent itself. Eventually, as it always happens, customers simply ask for more novelty.

Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated

Nike has lost 50% of its market cap since its peak, but is not trading like roadkill, either. Even today, it still boasts a P/E of 22. Still, wompared with an average of 30+ in the past years, it is “cheaper”. If the company recovered it will probably return to the previous high valuations. Let’s review what are Nike’s strengths, why its current challenges might not be so terrible, and what has to happen to turn the company around.

Fire power: Nike is so large that its marketing budget ($4 billion a year) is larger than the revenues of most of its competitors. This type of leverage is a huge competitive advantage in a world of infinitely replicable intangibles. Nike can afford to pay better athletes, designers, marketers and spread those costs over a revenue base that is 10x that of competitors.

In addition, Nike has $11 billion in cash and very cheap debt (yielding fixed at rates from 2.5% to 3.5% with more than half of the debt maturing after 2040). This provides the company with a lot of flexibility.

Innovation experience: As we will see later, many of the upcoming competitors, particularly in the running area, are relatively new companies that have not survived the passage of time through a few cycles of innovation/fashion. Today, the On Cloud or Hoka designs look innovative, but these brands have not totally shown that they can repeat those successes. In contrast, Nike has created several cycles of new silhouettes in the past. Nike has experience replacing a successful model with another successful model, therefore defeating the fashion cycle by creating its own cycle.

You rarely change until you fail: Nike’s non-innovation and classics-rehashing strategy worked extremely well until 2022. People went mad for seemingly infinite variations of the same silhouettes. If a strategy is working, it is very difficult to change it. Now that problems are patent, there is a lot more organizational consensus around the need to do things differently.

Rebuilding the foundations: The problem with returning to innovation is that many teams probably left the company. This is probably true for product functions (for example, when the sports divisional arrangement was changed to genre), but also of sales/channel functions (when wholesale was deprioritized). It may take time to rebuild the teams that can pull rabbits off the hat again. However, Nike has the monetary firepower to hire that people back. The story of ‘turning around Nike’ also provides the motive for successful managers to return to the company.

Waiting for the killing silhouette: If Nike’s problem has been lack of innovation, then it has to show innovation in order to win again. In the world of footwear, innovation means a new silhouette (also called platform or franchise). Therefore, my recommendation for investors speculating on a Nike comeback is to wait until the company reveals that type of innovative effort before considering the stock. It doesn’t matter if the new designs are great or a flop, but rather that the company shows that it is willing to offer something new.

On and Hoka, success in search of the second generation of franchises

One liner: Both On Cloud (ONON) and Hoka (part of Deckers, DECK) have been exploding as a great mix of function and fashion. The problem is that these companies have a single winning franchise. Therefore, they carry a lot of fashion risk. They still have to prove they can reinvent themselves at some point. On has, in part, already done this with the fantastic Roger model.

Running On Clouds: On Cloud started as a running shoe company with a very innovative midsole technology that was both well cushioned and light because of literal holes in it. The unique midsole also filled an important signaling and branding function. You could notice right away that these were On Clouds.

The company’s success exploded during the pandemic when it managed to ride the casualization trend. The Ons can be worn in relatively business-like settings because, unlike many running shoes, they have sober designs and colors (white, black, navy). On capitalized hugely on this lifestyle market by releasing a second silhouette platform, the Roger (from Roger Federer’s endorsement). Even more work-friendly, the Roger are discrete, extremely comfortable, and stylish. The company has been riding this wave, growing at 100% per year rates and 10xed revenues since 2019.

Strident Hoka: On the opposite side of the room, Hoka offers the market's largest, most colorful running performance shoes. The company was born as a brand for ultra-marathoners who need the maximum cushioning for their race days. Like On, Hoka exploded with pandemic casual runners and quickly became a function+fashion brand. Function, because the higher cushioning makes running easier for novices (although pros complain that the cushioning effect lasts less than 100 miles). Fashion because the shoes are big, super branded, and strident, providing a quick status boost to brand-hungry customers. The company’s sales have also 10x since the pandemic.

Iterate or die: The biggest concern I always have with brands that explode seemingly out of nowhere is that if one thing is certain in fashion, that is change. And whatever is massive at any point in time will be frowned upon ever more viciously later. This stems from the simple desire for belonging and differentiation. People buy into new forms and trends to belong to some circles and not others. Once a trend is spread out, the trailblazers move away, and, eventually, so does the imitating crowd.

This does not mean that On or Hoka are peaking now. God knows when fashion cycles change. However, at 87x earnings for On Cloud, and 30x earnings for Hoka’s parent Deckers (of which Hoka is the main growth engine), investors need to be pretty certain that growth will continue for quite some time only to break even, given that growth has to repay for all that multiple contraction in the horizon.

The only avenues for really long-term growth for a footwear company is a) no innovation, meaning a retailer with a great business model that carriers little fashion risk (think Zara), or b) a lot of innovation, so that the company is anniversarying its own products (like Nike).

The problem with On and Hoka is that they have not yet created that second franchise. Hoka is still iterating around the ‘flashy colors, huge size, lots of cushion’ idea, and On Cloud is still based on iterations of the ‘shoe with holes instead of midsole’ idea. On has in part reinvented itself with the Roger, so this is one encouraging sign. Still, I would like to see more rational multiples, and more form innovation before considering these companies.

Casualization fashion victims: Birkenstock (BIRK), Crocs (CROX), and UGG (DECK)

One liner: Birkenstock, Crocs, and UGG share a lot in common: category-defining products with roots in functionality and a loyal non-fashion motivated customer base. They added a lot of revenue from fashion-oriented customers thanks to the casualization trend. Now, they are exposed to fashion cycle risks, and their category-defining silhouettes become a liability.

Category-defining

These three brands have popularized a product so much, that the category is now equivalent to the brand. The silhouettes don’t look like any other product in the market. Of course, there are knockoffs and dupes, but this only speaks of the brands’ power. Furthermore, these brands do not need heavy logos or branding to make their product recognizable. The form is the brand.

Function-rooted and unfashionable

People initially chose Birks, Crocs, or UGGs because they are extremely comfortable to wear. In addition, Birks are very durable, Crocs are easy to clean and cheap, and UGGs are very warm. For a long time, these products were also considered unfashionable; too functional to be used in more demanding social settings. Wearing Crocs to a party would be considered a sign of lack of care. Wearing Birkenstocks was a hippie statement.

Loyal customer base

The fact that these products were not the latest trend but had great functionality led to the slow adoption by customers with relatively consistent demand.

In the case of Birkenstock, core customers become almost evangelists of the brand, owning several pairs. This is related to the brand's eco-friendly, left-leaning attributes, like being durable, made out of renewable materials, manufactured in Germany, and, yes, unfashionable (an attribute that many anti-consumerism consumers appreciate).

In the case of Crocs and UGGs, the brands became a staple of large customer segments, something to wear inside the house for comfort and that was automatically renewed when the product reached its end of life.

If these brands had stayed in this position, they would be among the best footwear businesses: the pricing (and margin) power of the brand, without the fashion cycle risk. Perfect.

The casualization boom

But then, the pandemic happened, and casual became fashion in a hitherto unseen way. Birkenstock went from hippies to affluent consumers; Crocs went from house only to something that can be worn to a party; and UGGs were included in the allowed winter feminine wardrobe.

This drove demand to unprecedented levels and allowed the brands to jack up prices and offer more fashionable (and expensive) categories too. All of these brands saw mid-double-digit growth in ASPs for 2022/23/24, on top of demand growth.

Who’s who?

The problem now is that it is difficult to separate the pre-pandemic loyal/staple demand from the post-pandemic fashion-driven demand for a variety of reasons:

The loyalists also increased their demand, as they were now in a position to either purchase more (stimulus), use more (casualization) or earn more status from the brands.

A portion of the fashion-fueled consumers will become loyalists, as the products still accomplish their original comfort function.

Part of the ASP increases were driven by selling more fashion-forward products at much higher prices. Examples are the Manolo Blahnik Birkenstock at EUR 600 or the Salehe Bemburry Crocs at $85 (vs $30 for the classics).

Fashion cycle risk is now higher and not priced.

As more customers purchased into the brands for fashion reasons, or the brands were able to offer higher priced products (driving ASPs up), these companies gained fashion cycle risk. Today, Crocs and UGGs are fashionable, but they will not be that way forever, simply because no silhouette is fashionable forever.

In the case of Crocs, the stock partly embeds this idea, trading at only 11x earnings. In contrast, BIRK trades at 87x earnings, and Deckers (the parent of UGGs and Hoka) trades at 30x earnings. The latter two valuations not only require significant growth to generate a modicum of return (Damodaran calculated 15% growth for five years at 20% margins for Birk to return 7%, and that was at IPO price of $40 versus $60 today), but also leave all of that fashion cycle risk unaccounted for.

Footwear fast fashion (Skechers, and Steve Madden)

These two companies are a beautiful mix of brand and retailer, like Zara or Uniqlo in the world of apparel. Their defining characteristic is that their brand is associated not with specific silhouettes or fashion statements, but rather with a specific price and quality area, which ties them more to a retailer than to a brand. Still, both make most of their revenues from wholesale but also have significant retail operations (Skechers in particular).

Skechers (SKX), the fast fashion leader in athletic footwear

One liner: Skechers is the closest thing in athletic footwear to Zara, Gap, or Uniqlo and is, therefore, more a retailer than a brand. It is not focusing on intangibles but on a consistent shopping and product experience. If they had some success in intangibles though, they could do extremely well.

Coveted successful model:. Skechers is relatively unassuming. It is not as famous as Nike, Adidas, Puma, or even the recent additions to the athletic pantheon like On or Hoka. However, the company has been growing consistently for decades, has reached revenues of $8 billion, and has compounded earnings and topline faster than all of the giants for the past decade. It also has a very unique sales channel strategy.

Value and quality without intangibles:. Skechers has built a very unassuming brand that is not fighting for leadership positions in sports but that customers recognize with value and quality. It does not have a lot of important endorsements and does not even try to compete in the performance/premium leagues in most categories, but is consistently considered a great value choice by reviewers and in forums. The company seems to have cemented this cost/quality leadership position. It also offers dupes of very famous sneakers at half the price, for example, the Skechers Onix at $65 vs the Adidas Stan Smith at $100. Sneakers got sued and lost on this model, but it does not get caught in many other cases.

Large partner-owned retail footprint:. One of the main differences between Skechers and its athletic peers is that Skechers has (but does not manage) a large branded retail fleet base. The company still derives 60%+ of its sales from wholesale (and probably more than 3/4 of volume), but most of its wholesale sales are to distributors and franchisees with Skechers branded stores. Skechers has 5,000 branded stores, 5x more than Nike, with 20% of the sales. This cements the idea of Skechers being ‘the place where you buy shoes’ with the margins of a brand.

Zara of footwear:. For these reasons (focus on value product and weight of owned retailing), I prefer to think of Skechers as the fast fashion leader of athletic footwear: a “brand” that concentrates on supply chain more than in intangibles, and that therefore has its competitive advantages in retailing.

Potential for the brand upside:. Skechers is dialing up its endorsement spending. Last year they entered basketball and soccer. Although its marketing expense is a fraction of the giants, the company has such a level of global penetration that gaining a little cachet could really boost its margins.

Steve Madden (SHOO), fast fashion for women footwear.

One liner: Steve Madden has one focus, to offer the shoes that are selling well at an affordable price to the masses. This makes it a fast fashion brand without large retailing operations.

Borrowed designs.: Steve Madden (the brand) takes its name from the designer, but the truth is that the company never invented much. The company is famous for its ‘dupes’ or look-alike of designer shoes at fractions of the price. These are not copies or knockoffs, they just look very similar, without any trademark violations.

The reliance on trends set by other people imply that Steve Madden cannot charge huge margins on its product, but also carries very little fashion risk. The company prides itself in having fast inventory cycles, and in ‘chasing’ demand. From a Nordstrom VP: They are one of the first brands to identify footwear trends and can move with speed to maximize the moment with product. This is the fast fashion model 101.

Focused structure.: SHOO’s structure is not cheap, at 32% SG&A to revenues. However, the company seems to be very focused, with most of the functions stripped to third parties. They obviously don’t do manufacturing, but also don’t do sourcing (working with agents), neither logistics (also third-parties). The company does some retailing (255 stores) but the majority of revenues come from wholesale (73%). The company’s CAPEX is less than 1% of revenues, and advertising is 4% (not too much, even for a retailer).

Ok margins, full returns.: Considering SHOO is in the brandless side of the continuum, their margins have been pretty good. The company’s operating margins were below 10% only during the GFC and COVID. SHOO’s capital returns are also high, with payouts matching FCF since at least 2018.

Small-cap brand conglomerates: WWW, DBI, RKCY, WEYS

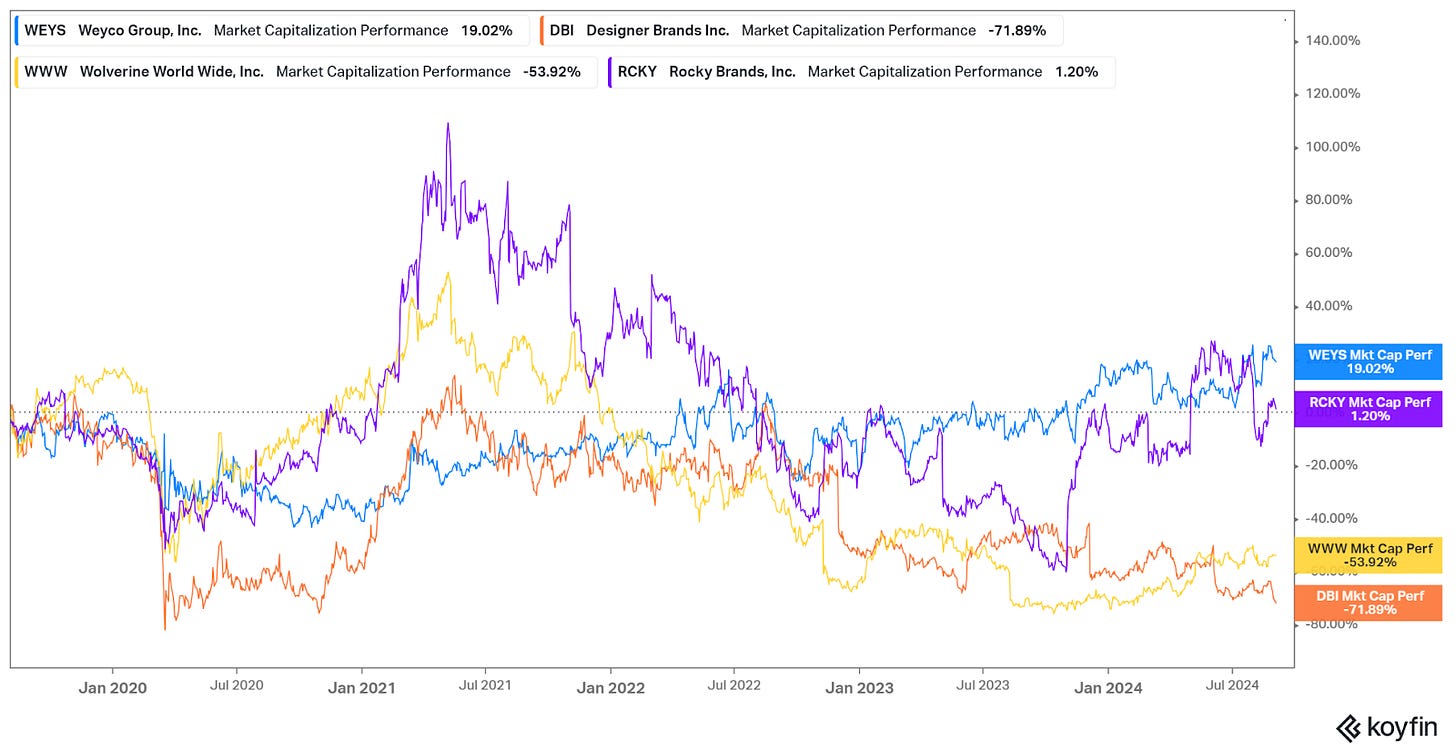

One liner: These small conglomerates are not great companies, with dubious acquisitions and too many unrelated brands. However, they trade like roadkill and could potentially be interesting as a back to normal trade.

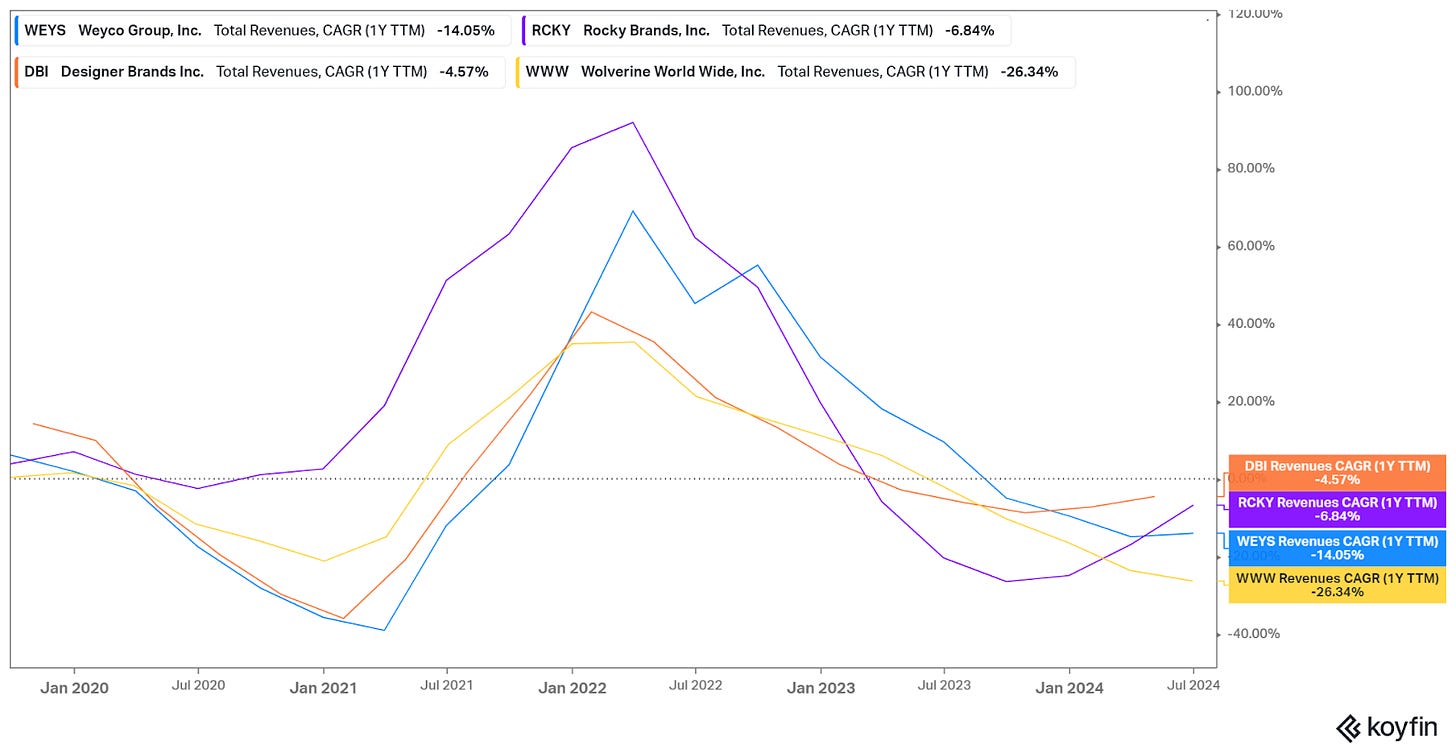

Our next stop on this train is the small-cap brand conglomerates Rocky Brands (RCKY), Weyco Group (WEYS), Designer Brands (DBI), and Wolverine Worldwide (WWW). These companies share a few characteristics and have operated very similarly recently:

Each owns many brands in very different categories. These brands are not the most important in their categories, but rather 2nd or sometimes 3rd tier.

Their sales followed the boom and bust of the post-pandemic. In 2021, demand exploded thanks to stimulus money, and demand repressed in 2020. This led to retailers increasing their orders to stock in advance, leading to massive surges of revenue for the brand conglomerates. Then, in 2022/23, consumers slowed down, and retailers were over-inventoried, leading to sharp declines in sales for the conglomerates.

Most of these companies trade at value prices predicated on a potential recovery of retailer demand.

Mix of categories with low-value brands

Unlike the companies commented on above (except maybe Deckers with UGGs and Hoka), the conglomerates in this segment have many brands spread over various segments. I think this level of dispersion is not great for conducting good branding activity and managing resources at the corporate level.

Wolverine owns Merrell, which is strong (but not a leader) in outdoors; and Saucony, a contender in performance running. These two brands make up 75%+ of sales. It also owns Sweaty Betty (a female activewear apparel brand), and Chaco (sandals).

Designer Brands owns Vince Camuto and Jessica Simpson (women sandals and dress shoes), Keds, Hush Puppies, and Le Tigre (sneakers), Topo (outdoors), and Lucky Brand (varied casualwear men and women). It also does a lot of retailing.

Rocky Brands operates in outdoors (Rocky, Georgia, Ranger), work footwear (Rocky, Georgia, Lehigh), western (Durango), and fishing/neoprene (XTRATUF, Muck Boots).

Weyco Group owns three brands in men's dress shoes (Florsheim, Stacy Adams, and Nunn Bush) and two brands in neoprene/outdoors (BOGS and Forsake).

With the exception of Wolverine, with Merrell and Saucony, or Rocky Brands, with Muck Boots, the brands named here are second—or third-tier, with little pricing power.

Clear pandemic boom-bust pattern

As the chart below illustrates, these brands went into a clear boom and bust cycle during the pandemic and post-pandemic period.

First, their revenues collapsed in the early pandemic, as their brands are relatively associated with outdoor or formal activities.

Then, with stimulus and the recovery in normal life, these brands could not fulfill retailer demand. Sales were booming.

Finally, people stopped purchasing for a variety of reasons: no more stimulus money and anticipated demand (how many pairs of outdoor boots are you buying each year? probably less than one). The consumer deceleration was multiplied by the bullwhip effect of retailers flush with inventory. These wholesale heavy companies saw their revenues collapse again.

In addition, some of these companies got into a lot of debt to either finance their working capital after the pandemic collapse or to make acquisitions. This is the case of DBI and WWW in particular (RCKY has been able to reduce its leverage. Their situation was precarious, and the stock prices collapsed.

Roadkill to not-so-bad trades

I try to buy shares of unpopular companies when they look like road kill, and sell them when they’ve been polished up a bit - Michael Burry

With these companies so hit by the mix of sales collapsing in 2022/23, they have become a speculative trade on a moderate recovery to pre-pandemic levels. The thesis makes sense because the revenue collapse was caused by two abnormal hits at the same time: first from consumers, who had purchased too much in 2021; second from retailers over-inventoried. This leads me to believe that the decrease is cyclical and will eventually recover. However, a potential protracted decrease in consumer discretionary income could mean some of these companies (particularly WWW and DBI, both highly leverage) don’t live to see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Footwear retailers: FL, GCO, SCVL, CAL

One liner: Similar to the small cap conglomerates above, the footwear retailers suffered from a peak in 2021/22 followed by a steep valley in 2022/23, from which they are recovering. The valuations are not super attractive unless one expects a return to pre-pandemic margins.

I originally posted about the footwear retailers when I covered the US apparel companies. Their situation is not very different from that of the small-cap companies, and therefore I won’t repeat it here.

Conclusions

The US footwear sector offers something for every type of investor: fallen angels (NKE) nosebleed growth (ONON, DECK, BIRK), compounders (SKX and SHOO), and rock-bottom deep value (WWW, DBI, RKCY, WEYS).

As always, my goal with the primers is not being conclusive about whether stocks are Buys/Hold/Sells, because that depends a lot on style and circumstances. In any case, having a base knowledge of the companies’ models, beyond of what can be grasped in their IR presentations and infinitely regurgitated in so many ‘analysis’ pieces will come in handy to keep an eye on the sector.

If you enjoyed this primer, subscribe to receive more, and please share it! It helps me a lot. Also, don’t forget to visit the Index for primers on many other sectors.

Very interesting DBI might be worth a look but timing is difficult

Interesting read!