Value hunting in apparel retailing.

Finding value in the debris after Amazon, Shein, and the macro.

Is there life after Amazon?

This article explores what can happen to retailers, specifically in apparel, in the long-term competition against Amazon, Alibaba, or Shein.

Can they survive? Can they thrive? Which ones?

Why talk about this?

For fun and profit.

Some apparel retailers worldwide are trading at low multiples. Many are considered dead men walking.

The culprit is long-term fear of the mega-retailers and short-term fear of the macroeconomy. The fears are absolutely justified. Many retailers don’t really have a viable model against Amazon, Walmart, Zara, or Shein. Some are operationally unprofitable and losing cash even today without a proper economic downturn.

At the same time some retailers are margin and financially strong to resist a macroeconomic downturn, and have a credible competitive advantage against the mega-retailers. Hopefully, some of those have low multiples, and we can find them.

I try to buy shares of unpopular companies when they look like road kill and sell them when they’ve been polished up a bit - Michael Burry

A technique that works repeatedly is to wait until the prevailing opinion about a certain industry is that things have gone from bad to worse, and then buy shares in the strongest companies in the group - Peter Lynch

A phrase by Charlie Munger that I can’t find that goes like ‘ There’s a lot of money to be made in the exceptions to generally valid rules’.

This article is an attempt to reflect on thumb rules to think about those retailers and their competition. I plan to complement it with an overview of most US apparel retailers in March or April, plus standalone articles on some quality retailers, including ex-US players like Zara or Renner.

TLDR summary

Value is subjective and not based only on observable qualities. This is especially true of apparel retailing (and if not, look at LVMH's 65% gross margins).

All great companies, including the mega-retailers, gain competitiveness by scaling and perfecting a value proposition. They cannot gain the same scale advantage if they manage hundreds of businesses, each with its own value proposition. Mega retailers have focused and excelled in value and assortment.

With its myriad subsegments, apparel has plenty of niches where even the Amazons or Sheins cannot compete with focused companies. The best niches are in high(er)-end apparel, whereas general ‘value and assortment at good price’ propositions are threatened.

Still, the managerial/physical barriers impeding mega-retailers from competing effectively in most niches have weakened as customer attention shifts online. The combination of VR plus generative AI could provide Amazon with a level of value proposal customization that is impossible today.

Fear around large store fleets is unfounded. Stores can be effective media and are already competitive with digital advertising costs. As long as the store fleet does not represent an assortment focus, and there is some strategic flexibility (like short lease average life), what matters is the result, not the medium.

That said, apparel retailers still suffer from reduced TAMs (the more segmented or niche the smaller TAM) and high end-market volatility (although good management can reduce this significantly). These factors call for higher discount rates when buying apparel retailers.

Finally, around macro-fears, not all customer segments are affected equally. A cycle-average model can work if the company is operationally excellent, and has a strong balance sheet to resist operational leverage.

In the beginning, there was the customer experience

If you read any account from a successful retailer, be it Sam Walton, Jeff Bezos, Amancio Ortega, or José Galló, they will focus obsessively on the customer experience.

There is only one boss, the customer - Sam Walton

Start with the customer and work backwards - Amazon Principle 1

A similar idea is the focus on service, value, etc. These are all ways of saying the same thing. For the unprepared mind, this sounds like management book gibberish. But it is not.

Because our primate minds are less than rational, we do not compare products based on objective measures with inter-temporal consistency. Instead, we ‘feel’ that some things are better than others. These feelings come from the subconscious and are only rationalized after the fact. They are full of biases, perceptions, and symbolism. They get stored in memory tied to a brand.

The customer experience is the cornerstone of retailing because value is perceived subjectively. The legendary retailers (on- and offline) understood that the ‘experience’ is way more important than the object of the purchase itself. Brands are built of the emotional memories that surrong this experiences.

Because value is subjective, customers don’t always choose the cheapest or objectively best option.

Whereas the platforms generally win in the objective arena, quality retailers can probably compete in the subjective arena.

How many business systems fit in Amazon?

Economies of experience and scale

Any company with a competitive advantage has a clear value proposition for its clients and does not deviate from it. The reason is that only via specialization can the company build the economies of scale that give it a competitive advantage.

These economies of scale are not only of the classical ‘bigger factory’ type alone. More generally, companies build economies of experience by improving processes and building systems that combine commoditized/objectively valued inputs into subjectively valued outputs.

Gaining experience and building a business system provides efficiency at the expense of breadth. The cost of having scale economies and efficiencies is to have a narrow value proposition.

Even material input scale economies are only relevant for some business models. Having the lowest cost of leather does not move the needle to Gucci, but it probably does for the value shoe wholesaler.

The scarcest resource, though, is top-talent time dedicated to consistently improve the operational details of the model. Top managers need to sweat it to create and maintain something truly competitive.

Great customer experiences are completely intentional. Nothing is left to chance or interpretation. Second, great experiences are the result of sweating the small stuff. - Doug Stephens

The value proposition and brand bottleneck

But… mega companies can afford to have two, three, or even ten business systems inside of them. Each can have more top talent and resources than the incumbents in a market segment. They can afford to lose money to gain experience.

True, although the subsystems probably share a series of resources and capacities that make the true core of any company, even octopuses like Amazon.

However, even the biggest companies have a single shot with their brand. Brands have to offer a consistent core value proposition. It is what will get imprinted in the customer’s brain interaction after interaction. Diluting it would mean collapse.

A single brand cannot be two things and even the largest companies have one flagship brand. They have to concentrate their efforts in this focal point and by result have to neglect other areas of the market that can be served with more tailored value proposals.

For example, Amazon executives debated extensively between quality vs assortment, and between first-party vs third-party (marketplace).

There was no way to follow both strategies simultaneously without jeopardizing the Amazon brand. Either Amazon had the most extensive assortment in the world, including premium and low-quality products, or had a selection of products that customers associated with specific value-price segments.

Amazon prioritized the marketplace because it leveraged its logistics and technology investments much better than selling first-party alone.

A managerial revolution

Amazon would dream of selling luxury to the rich, value to the poor, sophistication to the snobs, and simplicity to the laymen.

They cannot do this because of the limitations on how business systems and value proposition/brand pairs scale. However, they will keep pushing the barriers.

It is possible that its supply chain will become so efficient and automated, plus its marketing funnel so personalized that at some point, it will offer the greatest value for each particular customer segment. I’ll analyze some of this aspects in a following section.

But until then, there is hope.

Mega-retailers have to focus on a value proposition.

This stems from the fact that they have a flagship brand to protect.

Also, because talent resources to build effective business systems are scarce, even for these corporations.

Until a managerial revolution occurs and Amazon beats everyone at every possible game, there will be niches for quality retailers excelling in specific value propositions.

Apparel is a viable niche

As explained above, I believe there is room for quality retailers to compete with the giants because even those giants have limits on how many value propositions they can implement effectively.

In this section, I will try to outline which market areas show more promise of being outside the mega-retailers’ competencies and why apparel is one of those.

Shopping vs buying, differentiation vs cost

The degree to which subjective factors influence a sale is variable.

We have things like raw materials and commodities on the pure rational end. Qualities can be specified in minuscule detail, sellers are atomized, purchasers are professional.

Conversely, we have status objects like apparel and cars. The subjective aspects of these purchases are critical. There is almost an infinite space for brand differentiation, even when using the same inputs (same employees, physical locations, and garments).

Marketers refer to this continuum as 'buying versus shopping.’

Buying is mechanical, rational, and quantitative.

Shopping is creative, emotional, and qualitative.

Customers seek either money well saved or money well spent - Doug Stephens

Michael Porter’s cost vs differentiation framework stems from the same idea. The framework is generally summarized as cheap vs quality, but I don’t think that’s the case. I believe Porter’s cost strategy is more related to providing a good price/quality offer or more ‘value.’ The differentiation strategy focuses on more subjective factors.

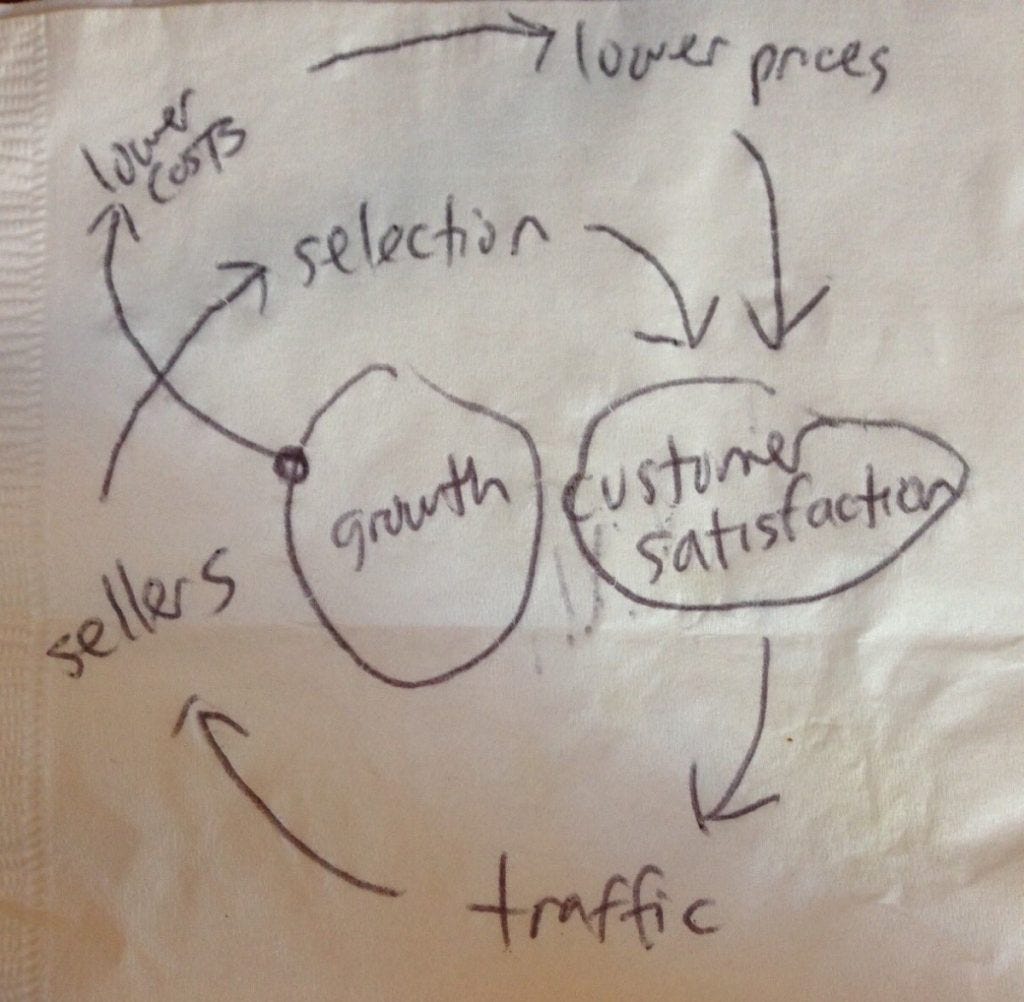

Mega-retailers are buying and cost

Mega-retailer scale advantages are enormous in many objective factors like costs, breadth of assortment, and ease of delivery. This was a conscious decision because these factors affect purchases in many categories and are, therefore, better to scale.

Bezos explained this in his famous napkin flywheel below.

At the same time, concentrating on the buying-type categories where people compare products on a more objective basis means that Amazon or Walmart are not competing as much in shopping-like categories where people focus more on subjective factors.

Shopping and apparel

Therefore, the first checkpoint a retailer has to pass is that its customers are not only looking for objective factors when purchasing. That is, they are not in a buying-type category.

Customers looking for good quality/price ratios, convenience, assortment, or the like will probably defect to mega-retailers. If you are rationally buying, you should buy from a mega-retailer.

We want customers to be a little higher on the Maslow hierarchy of needs, looking for objects to fulfill psychological needs like taste, refinement, identity, and community. It is in this category where mega-retailers have more trouble being multifaceted.

Some subsegments of apparel are an excellent category in this respect. Many people, probably the majority, lean more heavily into value than differentiation. However, the pockets where differentiation is important are large too, and generally wealthier. Even the customer buying mostly on price will want to differentiate himself by the apparel he wears.

Evidence that large apparel segments are run by subjective and not objective value is the gross margins in many luxury categories. Scores of apparel retailers have gross margins above 50%.

What about discount stores?

Some friends have pointed out that companies like TJ Maxx or Dollar General have done very well competing on price and assortment.

I think this does not conflict with the point.

First, these companies did excel with a cost strategy against mega-retailers, but by focusing on their blind spot niches. Particularly low-income customers.

Amazon and Walmart chose to focus in the affluent classes, it is a larger market. And they serve lots of low-income people too, but not as effectively.

A key to the discount stores’ success is also that their demographic is large enough to afford input scale economies.

There is an upcoming section on Shein and manufacturing cost advantages, too.

Most importantly, companies can win with cost/buying strategies, but it is so much harder than winning with differentiation/shopping strategies.

The reason is that the benchmark is objective in buying, be it quality, price, or both. If your focus is the lowest price, customers know exactly how to judge you against the competition. If your focus is identity, brand, or subjective value, you have more leeway in setting the benchmarks.

The reverse is that individual cost/buying markets are orders of magnitude larger than individual differentiation/shopping markets. Because companies can only choose to participate in so many markets, differentiation companies’ terminal markets are smaller and more volatile.

Physical versus digital

I think about brick-and-mortar stores, e-commerce websites, apps, and fulfillment centers as inputs. They should not matter by themselves. They should be arbitraged away because they are objective inputs (square meters of mall space, impressions on social media, packages delivered, etc.).

True competitive advantage lies in the business systems that combine commoditized inputs into subjective value. In this sense, I don’t believe that digital defeats physical.

Physical is increasingly considered a form of media and the only one (so far) that engages all senses. In terms of customer acquisition or advertising cost, it should eventually be similar to digital advertising (say, traffic versus impressions, accounting for targeting in digital).

However, I believe a solid digital presence is a must for a shopping-type apparel brand. The simple reason is that it is increasingly where people direct their attention all day.

This includes functional websites and customer service, plus reliable delivery and returns. Also, excellent content. Great pictures with brand-adequate models, engagement-inducing videos, influencers, live events, etc.

A stronger community can be built on social media than any store could imagine. Via content, the brand can help create a culture of which it is a part.

Mega media and organic customers

A concerning point, however, is how, as attention shifts from the physical to the digital world, the inputs become much more concentrated.

Store locations and traditional media are sufficiently spread out to generate competition and arbitraged markets. Amazon and SmallBrand compete substantially similarly when leasing a store or buying ad space.

But the digital sphere is increasingly concentrated on a handful of companies. We cannot assume arbitrage prices if the inputs are so concentrated. This can generate a profitability shift from the retail industry to the digital media industry.

What I’m saying is not new, the trend is evident and has made Google and Meta some of the most profitable companies in the world. The question is how this trend will advance and whether or not it will ever arrest.

Although I do not think that it is sufficient, proving to be able to build customer awareness and loyalty organically, be it physically or online, is a good starting point for competing against more concentrated advertising.

AI and VR

Another point is that in digital media and content, so necessary to build a brand identity, the management bottlenecks that prevent mega-retailers from occupying small niches shrink by the day.

Two developments concerning these new frontiers should worry anyone considering an apparel retailer investment.

The first one is generative AI. By slashing the cost of producing content and media and opening the possibility of almost automating the whole process, generative AI can potentially reduce the management bottleneck problem.

What if Amazon developed brand management software to create styles, images, videos, and customer interactions for small segments with little human intervention? What if via AI generated media, Amazon could mean something different for each person, or show a thousand faces?

The second worrying factor is VR, especially in combination with generative AI. VR can put digital experiences quasi-on par with physical ones. And again, managing and creating digital VR spaces can be automated and leveraged to a degree that is impossible in physical spaces.

The counterargument is that both generative AI and VR tools will be available for anyone as a service, just like building a commoditized e-commerce website in Shopify. Some people will still be more clever using these tools than others and may outcompete the mega-retailers in some niches.

True, but the limitations holding back mega-retailers in a VR+AI world are much smaller. Their leverage can be used much more granularly. It is important to remember that even today, Amazon has deep expertise in media.

Mega manufacturing (Shein and China)

A second concerning point is what happens when a company is extremely good at cost competition, generating a black hole that absorbs demand from the differentiation fringes of the market.

I do not claim that Shein is actually in that stage, but how it surprised the world thanks to its supply-chain capabilities makes me think that a company can slash the costs at the industry level, without compromising on assortment, and potentially on quality either.

The problem of buying versus shopping (cost versus differentiation) is much more pressing in this case. We can conceptualize any purchase as some part buying, some part shopping. As Shein (or other) slashes prices the buying considerations gain weight.

Thinking on the limit with the most differentiated brands, pricing does not matter (think Hermes). However, I would argue that, except for a few luxury retailers, there is a price/quality limit at which most demand defects to the best objective value.

Shein has shown that it can compete at bottom-low prices on low quality items with unlimited assortment (the famous 2,000 new SKUs a day). It mixed that with organically aggressive and brilliant marketing. The question remains whether the model can be expanded to higher qualities (transforming shopping into buying).

Company-specific characteristics

Focusing on shopping does not guarantee victory, only the possibility of competing.

However, if the retailer is not excellent, the mega-retailers will probably defeat them. The characteristics below are not very different from those of any quality company but are all the more important in retailing.

Customer (and efficiency) obsessive culture

Customer experience obsession means understanding how each factor in the company helps build a specific psychological outcome for the customer to maximize perceived value.

An essential sign of this obsession is actually defining the customer and the value proposition. If the retailer talks vaguely about their customers or seems to be competing on assortment, price, and quality (general categories), then it is not focused, and if it is not focused, it cannot compete.

Efficiency obsession means removing everything that is not conducent to more customer value. The best sign of this is cost control obsession and frugality. Corporate extravagance (G&A above all) is a bad sign.

If a company is customer and efficiency-obsessed, it will innovate and invest. This type of retailer will have things to mention every year’s earnings call. New inventory system, new store layout, better online checkout experience, etc.

Generally, these companies have a culture and have long-standing managerial teams. If they are young, it is all the more important that the customer and the value proposal are very clear.

Strong brand identities

This characteristic is a step deeper into the customer obsession.

It is logical that if a company has a strong customer value proposal, everything around its brand will reflect that value proposal. The reason is that a brand helps the customer identify the whole experience (and complete value) in the supply ocean.

The word of the game is consistency. The store (physical or not), the product layout, the level of service, media, colors, lighting, smells, music, etc., all have to point in the same direction.

Conversely, we can identify a lack of branding as undifferentiatedness. The store looks like any store, the website is a simple grid, the media presence is promotion-related, etc.

Value proposition frameworks: Stephens’ 10 retailer archetypes

Having models is very helpful in trying to understand a company, value proposition, and brand. Cost vs differentiation is one of those, but more granularity exists, too.

I can’t recall a lot of frameworks by memory, and I would like to make a checklist, so if you have any suggestions, write me.

For retailing and apparel, the retail futurist Doug Stephens proposed ten archetypes to identify value propositions that are consistent and relevant outside of the mega-retailers’ grip.

They are not the only ones, but they help pigeonhole a company. Companies belong to a few categories. If the company does not belong to any category, or only vaguely, it may be that the value proposal is not clear.

I have rearranged them in what I believe is a more relevant classification.

Product

Gatekeeper: provides access to supplies that are not available elsewhere.

Engineer: its products are exquisite in design.

Tastemaker: acts as a curator of enormous product selection.

Service

Oracle: provides expertise in a technical product category.

Concierge: extreme levels of customer service.

Brand/Culture

Storyteller: strong product identity related to a message, like ‘Just do it’.

Artist: the shopping experience is very artistic and creative.

Activist: have some embedded form of social change in their project.

Operations

Renegade: its operations are straightforward and cheaper.

Clairvoyant: predicts what the customer needs.

Physical heavy retailers

Generally, it is physical footprint heavy retailers that are more discounted than their e-commerce counterparts. We can delve more into why this is.

Large physical stores can be a sign that the retailer is competing on price and assortment, an area where it is very exposed to mega-retailer competition. Here, the problem is not the stores but the value proposition. The same retailer without stores would be in a similar problem.

Physical stores also increase a company’s operational leverage and impairment risk. The employees and stores cannot be abandoned to adjust expenses to demand and stabilize margins. If the company really needs to close stores, it will recognize large cash losses from right-of-use impairments and severance payments. In this respect, the recent macroeconomic fears fuel most of the low valuations.

One aspect I evaluate for this risk is the lease maturities.

Many apparel retailers are facing lease renewals for a significant portion of their store fleet, so they could walk away from stores at a low cost if necessary. On the other hand, if the store lease average life is more than 5 to 7 years, the company is fixed with its locations for good.

For large store format apparel retailers, an additional risk is that smaller store formats can bring the same marketing results at a lower cost. For example, by reducing the store space used for stocking inventory and using the store more as a gallery.

However, I do not believe physical stores are disappearing.

Physical stores are increasingly being considered another form of media or advertising expenditure. Having (mostly) fixed costs, they may be cheaper per customer acquisition than digital advertising, depending on the case. They are also the only form of media that combines all senses and is immersive (until we get into the metaverse, as discussed above). As mentioned previously, in the limit, the value of a store impression (traffic) should be similar to an impression in social media, adjusting for technical factors (again, unless digital media is a feud, as Varoufakis recently proposed).

For that reason, once I confirm that the company does not use the stores for stocking assortment and has some lease flexibility, I stop considering a large store footprint a liability. In my opinion, stores plus digital are a means to an end, which is value creation. Depending on the value proposition, stores can be extremely important.

Macro

The other half of the bear thesis of many retailers is that their profits will contract or disappear in the event of an economic downturn. In fact, for many, this is already a reality, and we are not even in a total downturn.

I believe key factors in this evaluation are operational excellence, operating and financial leverage, and customer segment-specific macro dynamics.

Operational excellence

This aspect was mentioned in the section on quality characteristics. It is obvious, but all the more important during turbulent times. Being good operators and stewards of capital is vital.

Without operational excellence, one cannot reasonably expect the retailer to recover from a negative cycle. This means that historical cycle-average profitability valuations are inadequate.

Customer segment specifics

Demographics react differently to macro events.

For example, I noticed that luxury brands are doing better than value in the current context. Part is explained by the strategic problem explained above, but it could also signal that the current economy is doing more damage to low-income people than affluent people.

Different regions of the country or the world could boom or bust at different rhythms. Oil and crops are high; rural America does well relative to low(er) income urbans. OECD countries are in recession, but EM demand is high. These are just made-up examples.

Operational and financial leverage, the importance of the balance sheet

But eventually, a cycle will hit the retailer’s demographic.

The problem is that retailers have embedded operational leverage. This is more so for B&M store-heavy retailers but also true for digital models.

B&M operational leverage is obvious, the stores can’t be closed, the employees can’t be fired. If the company is doing this, it is already in great danger.

But digital also needs volume. Distribution centers, inventories, and potentially manufacturing all need volume. It is marketing that is more adjustable.

I believe a solution to this risk is a strong balance sheet.

We can try to estimate breakeven points and potential downturn scenarios (severity and above all, length). How many losses and for how long can the company resist?

Of course, ideally, the company would be so excellent that it would not need to sustain losses during a downturn. But if it has to, the balance sheet will tells us how much it can live.

In this respect, adding financial leverage (and therefore gravely deteriorating the balance sheet) to an apparel retailer is terrible. It increases liquidation risk substantially. An exception is fixed or low spread debt at extended maturities, and below average ROCE.

I take advantage of the opportunity to promote ROCE.

I think it is the most important profitability metric.

ROCE is EBIT (or operating income, or FCF, or whatever you think is a good metric of true operational profitability) over capital employed.

Capital employed is some arithmetic around working capital, so I simplify to EBIT over total assets.

I believe ROCE best represents the profitability of the business (in all caps) than ROIC or ROA because these all differentiate equity from debt but use total assets, which are financed with debt.

ROCE tells me how well the stuff in the business is used, and then I can think about how it is ok to finance it.

If cycle-average ROCE is higher than the yield on debt (and the debt is long-dated so that it doesn’t introduce liquidity risk) then leveraging increases ROE, ROA and ROIC.

Valuation disadvantages of apparel retailers

Niche retailers have two features that make them deserve a lower valuation: market size and volatility.

A smaller TAM reduces the terminal valuation because after the ceiling, the company might not grow above or even with the economy. Realistic TAMs in apparel might be comparatively small.

As an example let’s think of a brand that targets high-income male teenagers. Playing with some numbers that are precisely incorrect but directionally correct :

13 million households, the richest 10% of the US population

$150 thousand average income

each household has a male teenager

2% of income, 0.5% for each member, used on apparel

30% market share

This results in a TAM of $3 billion. It's definitely enough for smaller caps, but it’s not gigantic.

The second factor is volatility, which demands higher earnings yields.

Depending on its value proposition, a retailer might be more defensive or discretionary. Macroeconomic regimes and cycles affect consumer segments differently as well, as discussed.

Another problem is vogues, especially so in the case of apparel. Brands, or even entire styles and cultures, can go out of fashion. However, managements bear most of the blame for this volatility. Customer-obsessive companies should lead customer trends.

Some retailers I have reviewed

This research was sparked by studying a great Brazilian apparel retailer, Lojas Renner, on which I’ll write a standalone article.

I have also reviewed other apparel retailers for Seeking Alpha. I hope to cover most US apparel retailers this and next month, and also some international ones.

Hibbett (HIBB)

Hibbett concentrates on selling Nike sneakers in small towns in the US southeast. Although I’m concerned about their dependence on Nike, I like that the company:

has a clearly defined customer: Gen Z fashion addicts.

has a very singular store footprint with low competition that has given the company some leverage with Nike.

is good at controlling SG&A and corporate expenses.

has shown innovation capabilities in the digital arena via a good app.

J Jill (JILL)

J Jill focuses on luxury casualwear for 45-65 year old women.

great gross margins of 65% talk of good branding.

there are other signs of high customer loyalty.

attractive demographic (no children, $150k average income, college graduate).

its value is differentiation by status: older women buy what the younger cannot, compared to Zara or Amazon.

great execution and a high ROE of close to 20%.

terrible compensation structure: CEO and CFO made $15 million between 2020 and 2021, based on adj. EBITDA targets.

terrible related party transactions with controlling PE firm.

highly leveraged.

Tilly’s (TLYS)

Tilly’s concentrates on adolescents with a surf/skater style and good prices. The company’s stores are heavily concentrated in California.

the focus on assortment and good prices is not great.

SG&A, even outside labor and rent costs, is not controlled.

their digital efforts are flawed, according to traffic and reviews.

CEO resigned last month, as sales continue to fall.

target customer is suffering more because of inflation.

strong balance sheet.

Citi Trends (CTRN)

Citi Trends concentrates on low-income African American mothers from the US’ southeast and Midwest. Their offer is assortment and very low prices.

again, focusing on assortment and prices is complicated.

labor costs are out of control, but the company did not save in other areas.

similar to Tilly’s, their customers are hard hit by inflation.

strong balance sheet.

recently removed three directors and reached an agreement with an activist.

Cato Corporation (CATO)

Cato was a leader in value apparel for teenagers, but its recent execution has been dismal.

competition on pricing and assortment.

stores look terribly old.

their designs cannot possibly target adolescents, as Cato claims. The brand got old with their 80s/90s customers.

SG&A expenses are totally out of control.

some people see a deep value play as the company’s EV is close to $0, but Cato is already generating cash losses that will shrink its net cash.

And that is the end

Thanks for reading! I hope you find it useful and, why not, entertaining.

I probably made lots of mistakes in this article. The logic has holes, the facts twisted. The narrative is boring and confusing in some portions.

But hey! I can improve for next time. So, I kindly ask you for a recommendation or comment, even a small one.

Also, if you liked it, share it. It means the world to me.

Shoulders of giants

Most of what’s in this article was borrowed. I can’t recall where I learned some parts. But the following books really influenced what I wrote.

Doug Stephenson, with his book Resurrecting Retail, gave me the idea of buying and shopping and the emotional aspects of retail.

Books of company/founder stories: Sam Walton’s and José Gallo’s autobiographies, the two Brad Stone books about Amazon, and Enrique Badia’s book on Zara.

If you have any recommended books or resources, tell me about them!

I absolutely love that someone did a detailed analysis of the apparel retail industry. I agree on the point that it is a viable niche market, and i also agree that the solution for each retailer is having a strong balance sheet so they can endure the current and future macrotrends. Which would also allow technological leverage in the future when AI+VR can be incorporated in some way to the stores, enhancing the marketing, and improving cost of storage margins.