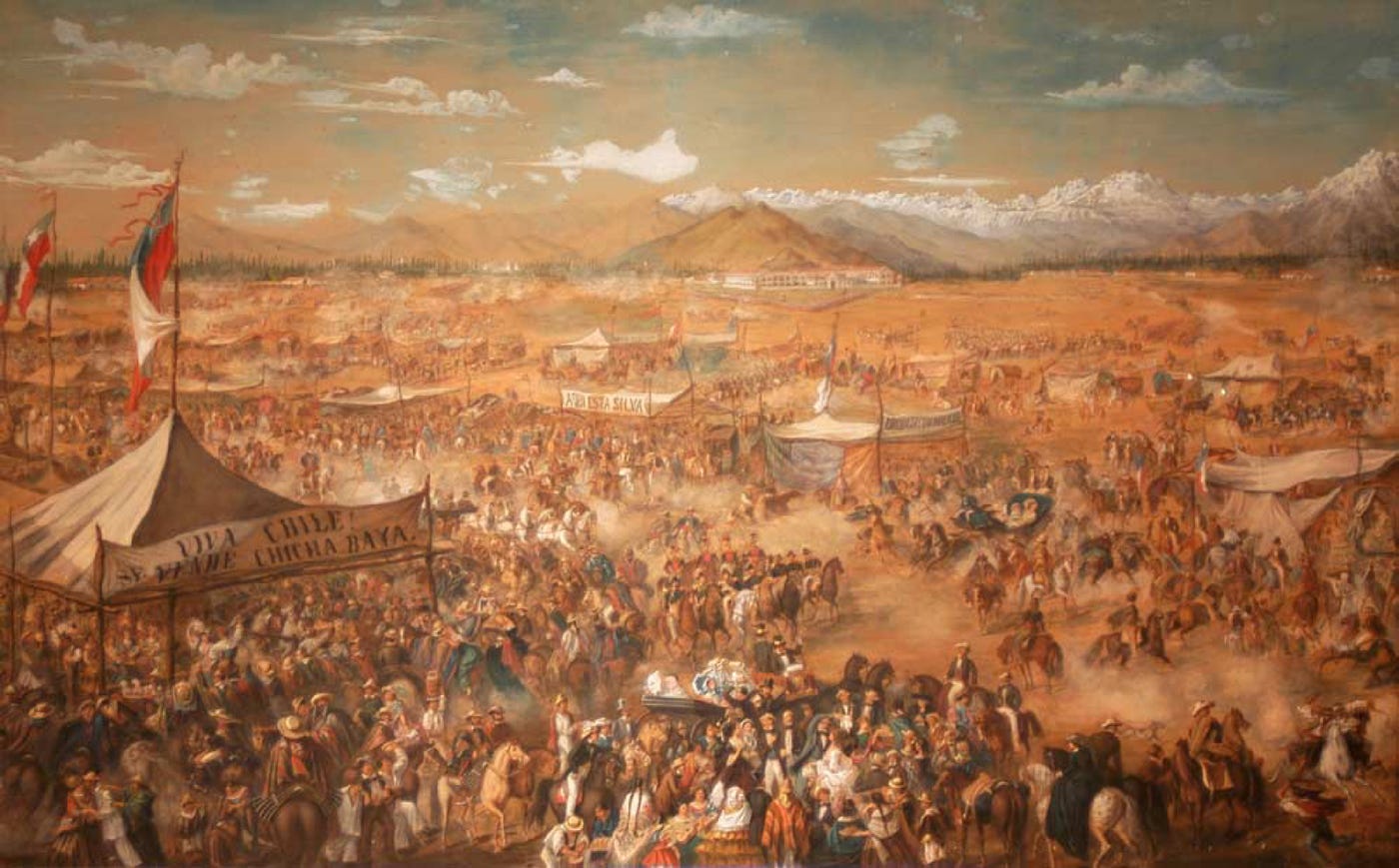

Following three decades of impressive growth up to around 2010, Chile’s economy and stock market transitioned from being a success story to becoming a poster child of post-GFC emerging market performance: sluggish economic growth, stagnant equity markets, currency depreciation, and political uncertainty.

However, since the pandemic, high copper prices—and the prospect of structural deficits in the material—combined with a 2025 presidential election where the right-centrist party has the upper hand, suggest that Chile could start to see market catalysts move in its favor. To seize the opportunities this potential shift may bring, it is essential to understand the reasons behind Chile's lackluster performance. Many factors are presented as plausible reasons, but to use history to understand the future, these factors need to be ranked and presented logically.

This article offers a short overview of the Chilean economy as it developed since the early 1980s, what changed post-GFC, how events led to the current situation, and how the cycle may turn more positive in the future. In addition, it provides an overview of the Chilean stocks accessible via ADR in the US and of some of the names accessible via the MSCI Chile Index ETF (ECH).

Index

Overview of the Chilean economy and history

The Chilean model: open, business-friendly.

Challenges to the model: the lost decade.

It’s the economy, stupid!

Reversal to stability?

Overview of Chilean ADRs and ETF: $ECH, $BCH, $BSAC, $SQM, $LTM, $ENIC, $AKO.B, $CCU, $ANTO.LN

Other Latin American country primers

El modelo: Overview of the Chilean economy and history

In this section, we will cover the basics of Chile’s economy: its reliance on copper exports, its diversification into other commodities, its open economy, and its generally positive business environment (vis a vis other Latin American countries).

We will also briefly cover its history, from the consolidation of the successful 1980s-2010 Chilean model to what can be considered a ‘lost decade’ since the GFC. We will discuss the drivers and potential explanations for this lost decade and whether or not we can expect a resumption of growth.

Summary

Chile’s economic model is still the most open, business-friendly, and export-oriented of the large Latin American economies. The model worked impressively well for the country for almost 30 years.

However, Chile’s economy and stock market peaked sometime around the GFC in 2012, and since then, it has been downhill in several areas. Growth has been increasingly sluggish vis a vis the US, and the stock market went from an average P/E of 17x up to 2015 to 8x in 2022.

There are many explanations: political conflict and polarization (particularly to the left), export prices collapsing, capital inflows reverting, lack of investment and growth, higher government spending and wider deficits, currency depreciation, challenging demographics, etc. The challenge lies in organizing these factors in a logical order, or at least ranking them by importance and impact, so that we can use them as a framework to anticipate potential shifts in the trend.

In my opinion, the original culprit was external shocks—specifically lower copper prices and capital outflows. This led to more political conflict, and growth in government spending and intervention, internalizing the growth problem. Politics failed to address the economic challenges, and now appears discredited. A reversal of these external shocks—mainly through higher copper prices and FDI— should restore political tranquility in a country historically known for its moderation. If that is the case, Chilean stocks could reprice to reflect prospects of higher growth in the future.

The Chilean model: open, business-friendly, export-heavy economy

Chile is the only (large) high-income Latin American economy (per capita GNI above $14k, Wikipedia). Particularly since the early 1990s, and into the early 2010s, the country grew much faster than all of its peers. This is based on a model of business-friendly regulations, moderate and centrist politics, sound fiscal and monetary policy, and export orientation.

Business-friendly: Chile is the highest-ranking Latam economy in the Ease of Doing Business Index (World Bank) and ranks second (above the US) in the Americas Index of Economic Freedom (Heritage Foundation).

Open: Trade makes up more than 60% of the Chilean economy, ranking similarly to high-income countries and 10-20pp above the Latin American average (World Bank). The country has signed 33 trade agreements, including free trade agreements with most Latin American countries, the US, Canada, Mexico, China, Australia, Vietnam, and South Korea, plus trade agreements with the EU and Japan (US ITA).

Commodities-oriented: The country’s exports make up between 30/35% of its GDP and are extremely oriented to commodities, representing more than 90% (OEC). Metals make up 50%+ of exports (copper is 45%), chemicals another 15%, and another 20% comes from edibles (fruits and fish mainly).

Transition minerals hub: Chile is the largest player in the global copper market, with 25% global production and a similar figure for reserves (USGS). It also plays a key role in lithium, with 24% of production and ⅓ of global reserves (USGS), although falling because of exploration (CoChilCo).

As mentioned, copper makes up 45% of Chilean exports today, but it was closer to 60% when copper peaked between 2008 and 2012 in the last commodity bull cycle (OEC).

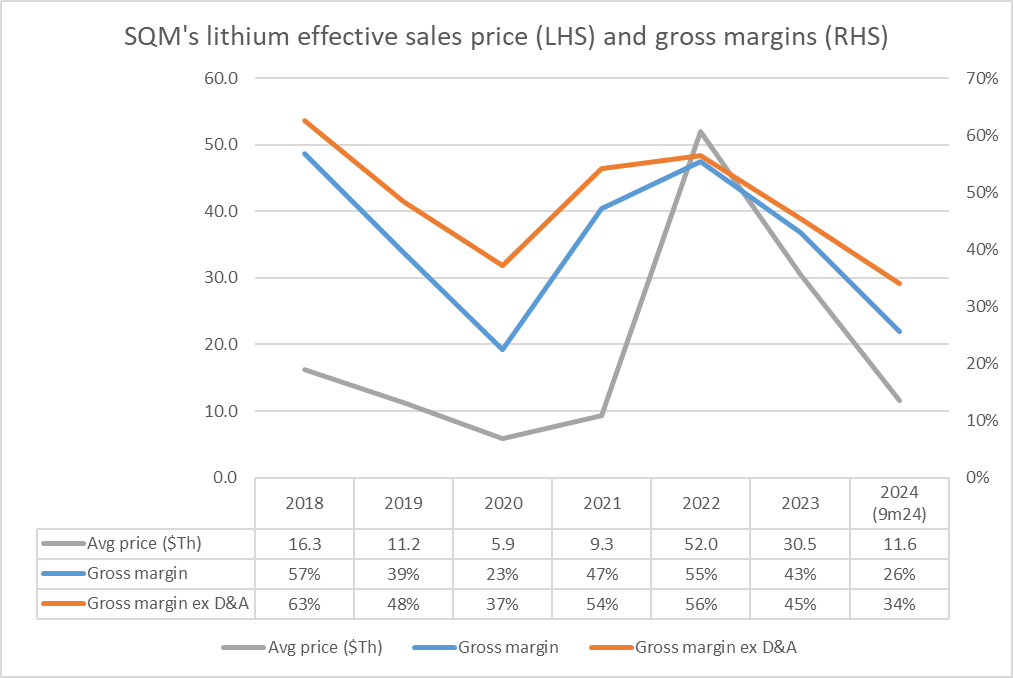

Lithium is much smaller, but is growing immensely fast as a mineral driver of exports. In 2021 lithium still represented less than 1% of Chilean exports (~$1 billion), to reach 8% in 2022, at record prices (Chile Central Bank). Since then, lithium prices have collapsed and production has stagnated around 275/300 thousand tons of LCE (CoChilCo).

Politically moderate: After the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990, and responsible for setting the institutional bases for the Chilean model), Chile lived in a bipartisan system, between a center-left and center-right government. Moderation and conservatism became the norm. As a famous Argentinian soccer trainer once said, ‘You don’t change a winning team,’ and with the country experiencing tremendous growth, there was little incentive to challenge its model. While this has shifted in recent years, even in its more radical moments, Chileans remain a society inclined toward moderation. For example, hard-right candidates show admiration for Milei’s growth in Argentina but are quick to clarify that ‘nothing so extreme is necessary in Chile’ and that they share the economic ideas but not ‘other values’.

Challenges to the model: The Lost Decade

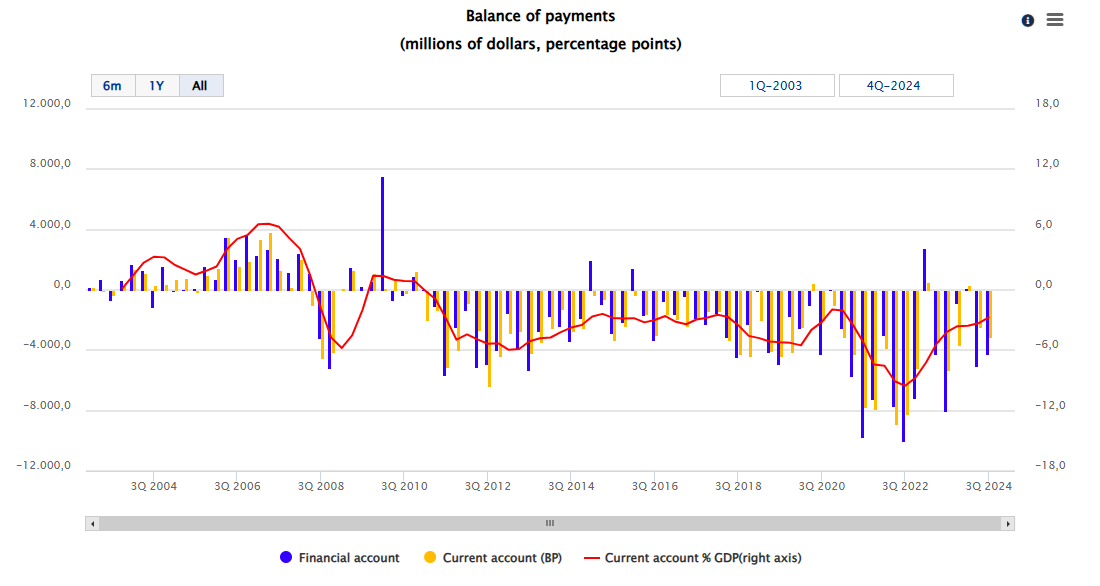

After the GFC, Chile’s model stopped working as smoothly as before. Growth has been much slower, compounding at only 1.9% between 2013 and 2023, compared to 9.6% between 1990 and 2013 (World Bank). The country went from a capital surplus on the current and capital accounts to a deficit on both of them. The government budget went into deficit, and investment fell.

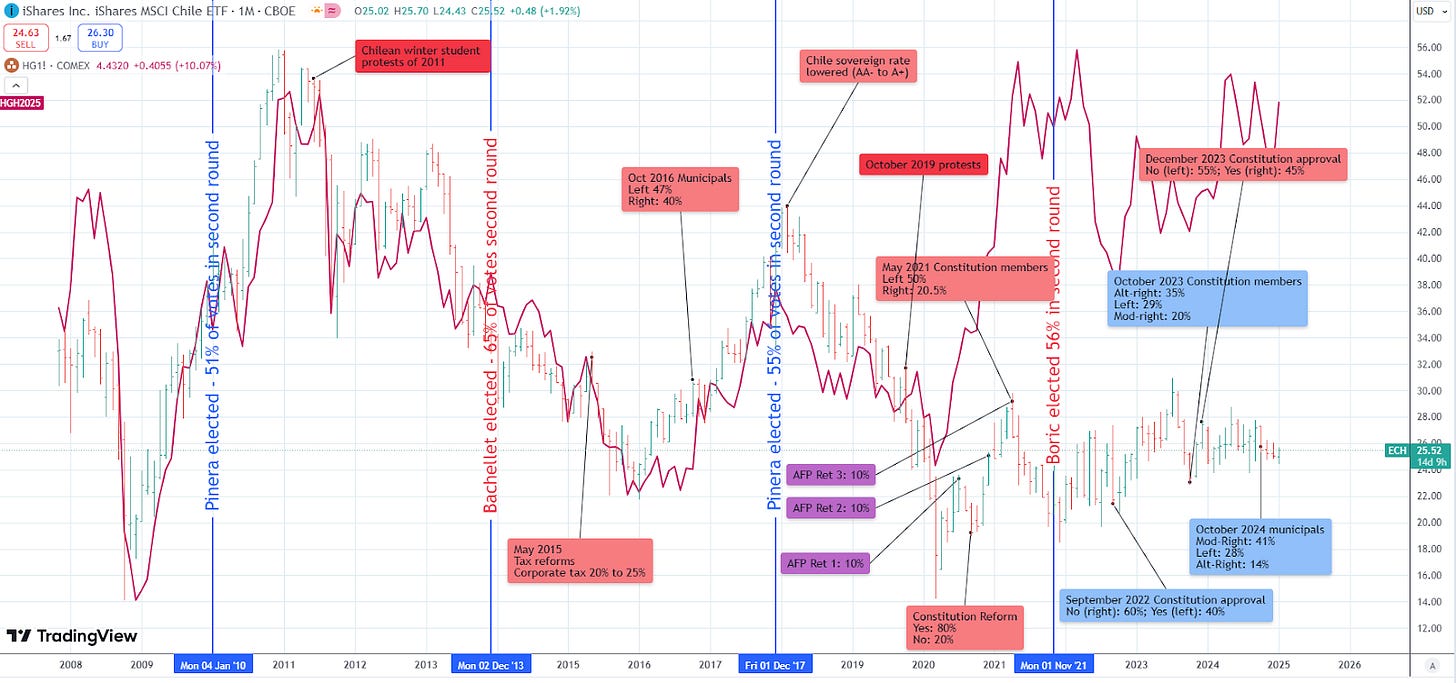

Most important for investors, the Chilean stock market has been terrible. The MSCI Chile Index ETF (ECH, Yahoo) is down 70% from its peak in 2010 and has been flat since the pandemic, barely a few percentage points above the COVID lows. The Santiago Exchange Index (IPSA) P/E ratio went from always above 17x until 2018 to a low of 8x in 2022 (CEIC).

It’s the economy, stupid!

Various factors have been suggested as potential explanations for the shift in Chile’s trajectory. Many attribute it primarily to political issues and uncertainty about the rule of law, arguing that these hampered the model. However, I do not believe this is the case, at least completely.

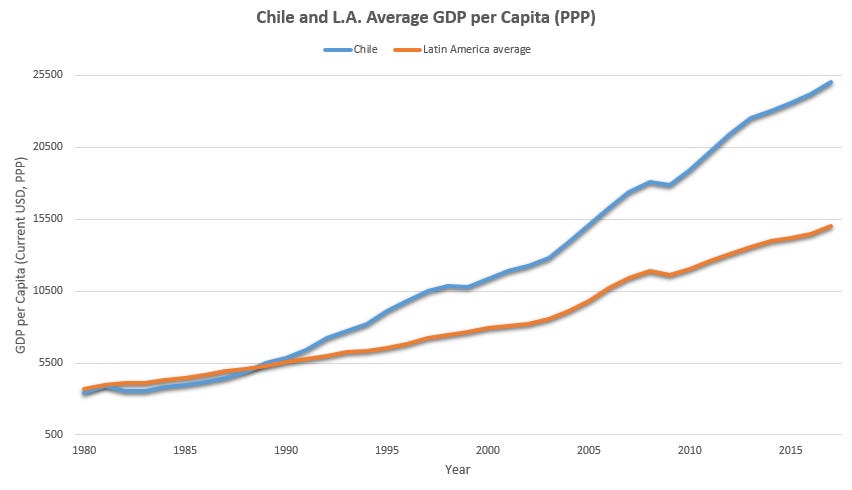

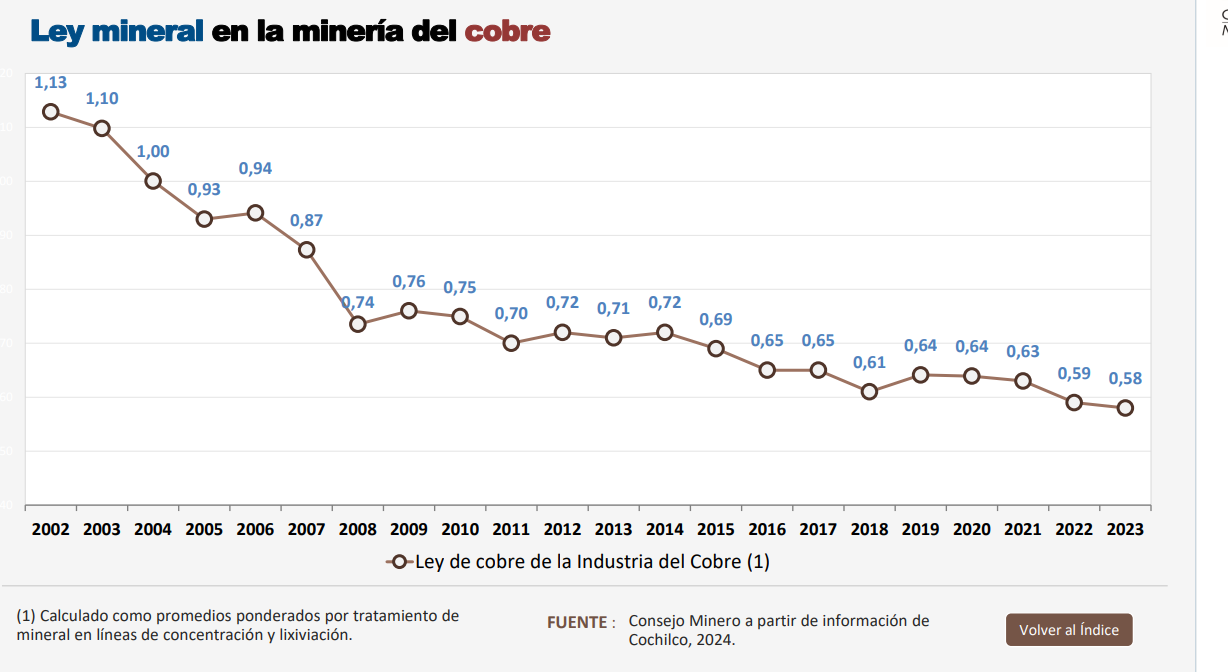

In my opinion, the collapse of copper prices set off fiscal and social challenges that made growth more difficult, which ultimately culminated in political instability. That is, it was the external shocks —mainly related to copper—which initially hit the country, but over time, these issues became politicized and internalized.

This is evident in the chart above, comparing the Santiago Exchange Index (IPSA) with copper prices, showing a very clear correlation that breaks after the pandemic, when the political process becomes highly radicalized and entrenched.

But, how did events unfold?

Copper prices and grades collapsing

Copper prices went from $0.5 per pound in 2003 to $4 in 2008 and up to $4.8 in 2011. This was the boom period of commodities and emerging markets, with China driving a voracious and (assumed) insatiable thirst for natural resources. However, like all commodities, the cure to high prices is high prices, and eventually, the copper cycle reverted. By 2016, copper prices halved, reaching $2 per pound.

The decrease in price was matched by a decrease in mineral grades (the amount of copper obtained from the rock in the mines). Whereas the average copper grade in the country was 1% in 2004 (you have 1kg of copper for every 100kg in the mine), this decreased to 0.7 in 2011 and 0.65 in 2016 (Chile Mining Council). If copper yields fall to ½, costs go up by approximately 100%. In order to obtain 1kg of copper, the miner has to blow up, grab, transport, and process twice the amount of rock.

Copper represented 57% of Chilean exports in 2010 (OEC), so the economic hit was fierce, mainly via investment and employment. Chile’s growth fell from 6.2% in 2012 to 1.8% in 2014 (World Bank).

Reversal of capital flows and currency depreciation

With falling profitability for copper and a risk-off environment with a flight to quality, the Chilean balance of payments reverted and quickly went negative. Goods trade surplus went from $22 billion in 2007 to negative $1.2 billion in 2012, and FDI peaked at $30 billion in 2011 to $5 billion in 2017 (Chile Central Bank).

The result was pressure on the currency, with the Chilean peso depreciating 100% from CLP 460 per USD in 2013 to CLP 723 per USD in 2017 and now at almost CLP 1,000 per USD (TradingView). In a trade-oriented country that imports 40% of its GDP, a depreciation severely impacts the cost of living.

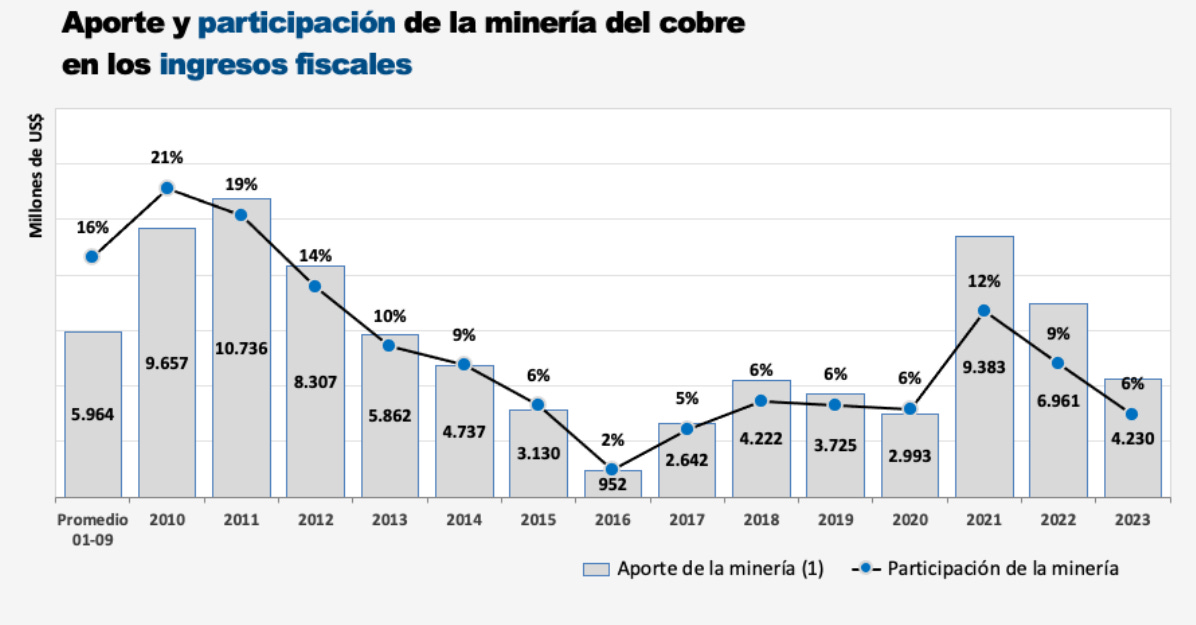

Collapse of fiscal revenues

The chart below shows the contribution of copper mining to fiscal revenue (the bar is USD billions, and the line is the percentage of all fiscal revenues). Copper revenues went from 20% of all fiscal revenues to 2% in a span of five years, at the same time as the government needed to increase expenses (Chile Mining Council). Imagine the fiscal impact of losing 20 percentage points of fiscal revenue in 5 years.

Start of political conflict

An external shock to an economy naturally leads to more political conflict. Finding jobs is harder, running businesses is harder, etc. Someone has to ‘pay’ for the damage, and society starts asking for someone to blame and punish, even if the reason for the shock did not come from inside the country.

This is when large protests started in Chile. In 2011, student protests asking for reforms to the education system (lower interest loans, illegalization of for-profit motives, and more investment in public schools) led to the dismissal of the Minister of Education. These protests gathered almost 1 million people (in a country of 17 million at the time) and lasted for several months (Wikipedia). The leaders of the student conflict of 2011-2013 would then join the Parliament in 2013 and become the government leaders in 2022 (including Chile’s President Boric, back then President of the Chile University Federation, and elected to Parliament in 2013).

The political conflict internalizes the economic challenges.

As social demands mounted, a central-leftist government was elected in 2013, and radicalization was already visible. Whereas Michelle Bachellet’s first government (2005-2009) had been considered centrist and moderate, the discourse had totally changed by 2013. Student leaders from the protests integrated the parliamentary roster, and the new government promised to advance educational gratuity, constitutional reform, and a series of other progressive actions.

With copper prices down and a desire to spend more, the government’s deficit widened, and a need for new resources became apparent. Bachellet’s government took almost $4 billion per year from the sovereign fund, and the deficit widened every single year of her mandate (IMF), even though Congress passed a fiscal reform that raised corporate taxes from 17% to 27% over six years (2014 Tax Reform).

Political conflict entrenchment and constitutional reform

With the economy deteriorating further and the political system incapable of providing answers, discourses on both sides became more radicalized, leading to a high conflict period between 2019 and 2023.

In 2019, new protests erupted after an increase in the price of the metro. The massive and violent protests are called the Octubrazo (October is quite a revolutionary month in history, by the way) and remain a hinge point in Chilean political history (Wikipedia). The protests would live on with different intensity until 2021.

At this point, Chile’s ETF (ECH) loses its correlation to copper (even though, as we will see, the ETF has never had direct exposure to copper). It is a sign of the inward orientation of trouble in Chile.

The conflict and deteriorating economy, aggravated by the pandemic, led to landslides for the left, including the votes for constitutional reform in 2020, the left's victory in the constitutional committee, and the election of Boric (a student leader from 2011) as President in 2022 (Wikipedia).

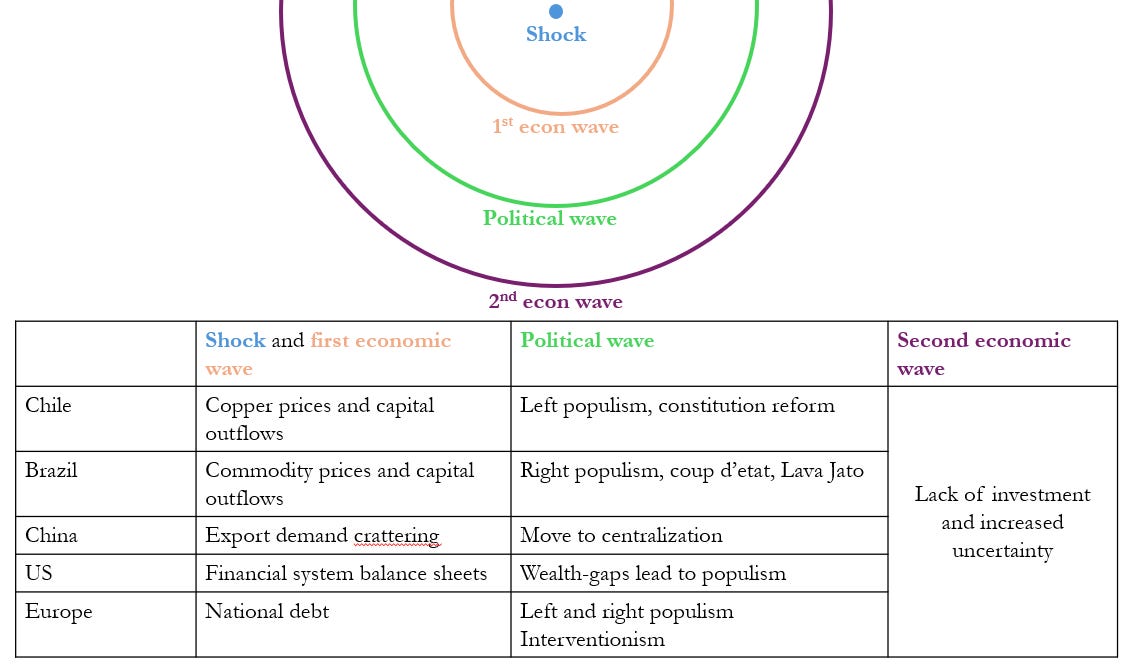

Lessons from Chile: the challenge of managing the cycle

If there’s one key takeaway from Chile’s experience after the GFC and the commodity bear market, it is this: it is extremely difficult for a country’s political system to deal with a negative business cycle. The political difficulty of managing such cycles—often marked by social conflicts—tends to drive institutional change, which, in turn, generates additional economic turbulence.

Chile is far from being an isolated case. Across Latin America almost every country went through the same process: more open and less interventionist economies (such as Peru and Colombia), and less open and more statist ones (Argentina, Brazil), all faced economic challenges leading to political instability which generated more economic challenges. Beyond Chile and its region, almost every emerging market went through similar challenges (revolutions in the Middle East, populism of left and right in Europe and America). The political wave then collides with the economic wave, amplifying and prolonging volatility.

In fact, Chile, compared to peers, is actually an example of solving the problem moderately: no coups, no massive reforms to institutions, and no tremendous examples of right or left populism.

Therefore, as students of the markets, the lesson broader lesson is clear: economic shocks rarely die out. Rather, they reverberate through the political system, creating feedback loops that ripple back into the economic system.

Potential changes in trend?

Many of the factors (both economic and political) contributing to Chile's negative trend are reverting, potentially signaling a return to more interesting growth and a repricing of its equity markets.

Moderation of the political spectrum

Although the political process radicalized, it ultimately achieved little. The ultra-leftist initial draft of the constitutional reform was rejected by popular vote in 2022. A new constitutional committee was elected in 2023, this time leaning toward the alt-right, with the centrist-right displaced as the main opposition. Yet again, the right-wing draft was rejected by the public.

As a result, the Constitution established in 1980 by Pinochet during his military regime, which underpins the Chilean model, remains in place.

Both the hard left and right saw their reputations tarnished. The winners in the 2024 municipal elections were the center-right parties, going from 87 municipalities in 2021 to 122 in 2024, whereas the left (center and hard) went from 153 in 2021 to 111 in 2024 (2021 Wikipedia, 2024 Wikipedia).

Upcoming elections in November 2025

Chile will elect a new President in November 2025. The center-right candidate Matthei has the highest support (28%), followed by the alt-right candidate Kast (10%) and two times president Bachelet (11%, center-left) (Wikipedia).

The Chilean presidential election has a two-round system. To win the first round, you need at least 50% of the votes; otherwise, two candidates advance to the second round. This implies you need at least 50% population support to win. Therefore, the main risk is that a candidate from the right of the spectrum is so hard that it alienates the moderate population to the left. This is what happened in 2022 (when Kast, the alt-right, lost against Boric, presenting himself as more moderate).

The economy and social justice are no longer the most pressing issues for Chileans, who are somewhat ‘tired’ of the political conflict process. According to polls, the most pressing issues for Chileans are security (60%) and immigration (40%) (IPSOS), both related to massive Venezuelan migration to the country (Chile has received 2 million migrants since 2010, in a country with 17 million people). Unemployment, inequality, and inflation are behind at 25% and 30%.

Trade and FDI are recovering

Chile recovered its trade surplus of $4.5 billion in 2023 (the first time since 2012, except for 2020). By 3Q24, it had doubled to $10 billion. FDI has also turned positive. Gross FDI bottomed out at $5 billion annually in 2017 and increased yearly until it reached $21 billion in 2023 ($13 billion as of 3Q24) (Chile Central Bank).

Copper is one of the main drivers of that investment and trade recovery. Mining projects announced for the next decade reached an all-time high of $85 billion in 2024, up from a low of $45 billion in 2016 (Chilean Copper Commission).

Conclusions

The 10+ years of economic and political struggle following the commodity bear market appear to be nearing an end in Chile. In a reversal of the dynamics observed after the copper shock, the reverberations of a positive economic shock —driven by higher copper and lithium prices and increased FDI— can lead to a more moderate political environment characterized by a pro-business sentiment.

If the above thesis is correct, then the market is ‘behind’ the developments, still perceiving Chile as a struggling country, even as signs of economic recovery and political cohesion are already sprouting.

The elections in November 2025 could serve as a catalyst for this sentiment change. Even if they don’t —for instance, if a leftist government is elected—, a continued economic recovery would likely pave the way for more pro-market policies. Ultimately, Chile would see a market revaluation as these dynamics play out.

Overview of Chilean ADRs and ETF

Thinking about the future is always hard, but having a framework as the one I presented above is at least a basis for the discussion, and choosing which factors to pay attention to.

Still, the goal of the market student is to be correct more often than wrong, or to benefit more from being correct than what is lost from being wrong. This requires that on top of a country thesis view, we add specific company and stock analysis, in order to stack the odds favorably so that in the case of a recovery we benefit, and in the case of a lack of recovery or deterioration things don’t get too bad. In the best case, the companies are so good and undervalued by themselves that don’t even need a sentiment change.

This section tries to provide an overview of the Chilean equities widely accessible through US markets. The goal would be to find a security that has positive trends and yet is undervalued because of the sentiment towards Chile in the market. I think several of the names below fit in that read. However, as this is only an overview, it does not include an in-depth analysis of each company. Conclusions, particularly for those with significant exposure to commodity prices, remain open and will be explored in further articles.

Available securities, exposure to the economy and sentiment, summary.

Unfortunately, the ADR selection for Chilean companies is quite limited.

There are 7 Chilean ADRs trading in the US, two of them in banks (Banco de Chile $BCH and Banco Santander Chile $BSAC), one in lithium mining (Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile $SQM), an airline (Latam $LTM), an energy generation and distribution utility (Enel Chile $ENIC) and two beverage manufacturers (Embotelladora Andina $AKO and Compañías Cervereas Unidas $CCU). There is no consumer discretionary, retail, real estate, capital markets, chemicals, fruits and seafood, etc. There is not even a copper company.

This puts some challenges to expressing a fundamental Chile view because the most ‘sensitive’ sectors generally are in consumer discretionary, or capital markets for a sentiment view. Still, there are some things we can work with:

The iShares MSCI Chile Index ETF ($ECH), or the Chile ETF for short, includes 47% of the ADRs mentioned above, and no copper, but some consumer names (although as seen below they are diversified into other countries). It can work as a pure sentiment idea potentially.

The only way (that I know of) to access a pure-play copper miner in large international markets is Antofagasta Mining ($ANTO.L, $ANFGF), which is the third largest producer behind the state company and BHP. It trades in London, and indirectly in the US via unsponsored ADR. The rest of the large copper miners are diversified majors (BHP, Anglo, Rio Tinto, Freeport-McMoRan, Lunding) and the State company (CoDelCo). Still, if the view is purely copper, there are other companies available (I don’t have a copper view but remember the impressive performance of Southern Copper Company $SCCO from Mexico).

Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile $SQM, is a very interesting lithium play, with a valuation of 10x P/E based on a (potential) down cycle of lithium. The company may be responsible for 25% of lithium global production this year. More work is needed on the economics driving the lithium cycle and on the changing regulatory agreement for lithium on the country (mainly 2030-2060 management of the mines via JV with the government company).

The two banks, Banco de Chile $BCH and Banco Santander Chile $BSAC, are exposed to the sentiment via capital flows because an appreciating currency tends to benefit the banks a lot (as their balance sheets are generally in local currency). The contrary is also true, with a depreciating currency hurting them the most. These banks are ok, but I don’t think they are examples of super operations, or that they are particularly cheap now on a fundamental basis.

Latam $LTM is a Latin American airline, the largest operating mostly locally, and only a portion of its operations are Chile-based. Still, the name is interesting because it is the only large public airline in Latin America that restructure post-COVID, making its financial expenses much lighter than competitors. This, and this alone, is the basis of its profitability, compared to peers. More work is needed on the sustainability of its current capital structure.

Enel Chile $ENIC is the largest utility of the country, and therefore is also exposed to capital flow sentiment via appreciation of its CLP denominated earnings. The name seems interestingly priced because of a series of regulatory and climatic challenges, stemming from a large short position in electricity between 2021/23 when hydro production in Chile collapsed at the same time as LNG prices exploded. Also an interesting name for sentiment.

The two consumer defensive/discretionary names available are Embotelladora Andina $AKO and Companias Cerveceras Unidas $CCU. They are a mix of defensive and discretionary because soft drinks and alcoholic drinks (particularly the latter) do move with disposable income. They are also very diversified to other Latin American countries (mainly Argentina, Brazil, Colombia), so Chile is only one of the drivers for a fundamental view. Andina seems much better managed than CCU, in my opinion, and also seems cheaper.

iShares MSCI Chile Index ETF ($ECH)

The Chile ETF offers some additional exposure to the Chilean economy that is unavailable via ADRs because it can invest in local names of the Santiago Exchange. It also allows one to express a country view without a specific company view.

It does not include Antofagasta or any copper company, so it does not have direct exposure to copper. It includes some consumer discretionary and defensive (a total of 27%, of which Andina and CCU above are 5%), more banks, real estate, and industrials.

The problem for expressing a consumer view is that those additional consumer companies (mainly Falabella, Cencosud, and Copec) are highly diversified into other sectors and countries, making them not very Chile-consumer-specific. I am not particularly interested in them because they are not super cheap, but, to be honest, I have not done a lot of work on them because they are not individually accessible from outside Chile, and they have diversified away from Chile or the consumer.

Falabella owns the namesake department store chain. These are large mall-type buildings with floors dedicated to different categories (mostly apparel, footwear, fragrances, and appliances). It also owns a home-improvement and construction chain called SODIMAC, 2.5 million square meters of gross leasable area on its malls, and a financial services arm (mostly to finance its retail operations).

The company could be considered an interesting player in Chile, but only 50% of revenues come from there. The company has large exposures to Peru (26% of revenue) and Colombia (17%).

It trades for about 15x cycle-average earnings and has not grown income (in CLP, halved in USD) in the past 10 years. In my opinion, it's not particularly attractive to express a Chilean view.

Cencosud owns supermarket chains, including two premium/affluent ones (Disco and Jumbo) and two home-improvement ones (Easy and Blaustein). Again, only 44% of revenues come from Chile, with 18% from Argentina, 12% from the US, 11% from Brazil, and then Peru (7%) and Colombia (6%). Also at 20x earnings, it doesn’t particularly strike me as opportunistic.

Codec is considered a consumer company because it owns gas pumps in Chile (a segment responsible for 45% of its EBITDA). On the other hand, it also participates in pulp, paper, forestry, and woods (the remaining 55% of EBITDA).

Banco de Chile ($BCH)

Share and principality: Banco de Chile is one of the largest in the country by market share, but it’s not super dominant, at 15/20% of assets and deposits (other large banks include Banco Estado (public), Itaú, Santander, BCI, and Scotiabank). It has a strong principality position, with an average balance per retail customer of two times its competitors, and 22% of its assets on mortgages.

Assets and services: The bank’s core activity is wholesale lending to commercial customers (mainly other financial services and real estate, on working capital lines), for 35% of assets. Then, as mentioned, 22% for mortgages. Government lending (12%) and consumer (10%) are not as relevant.

Currency exposure: The bank is heavily positioned in Chilean currency, with something like 40% of assets in Chilean pesos and another 40% in Unidades de Fomento (UF), an inflation-tied currency unit from Chile. This has made growing the balance sheet on USD challenging because of the depreciation. This gives the idea that the bank has been stagnant when it has almost doubled in CLP's (versus 56% compound inflation 2013-2023).

Rates exposure: The company is somewhat protected from rate fluctuations via low exposure to USD (15% of liabilities) and moderate exposure to loans (30%), compared to demand deposits (25%) and time deposits (30%).

Inflation exposure beneficial in 2022/23: Because the bank had a net exposure to UF (inflation-adjusted units) of almost $10 billion, it benefited from Chilean inflation going to 12/13% for a while. Since then, inflation has returned to more moderate levels, and UF loans are not more profitable than CLP loans.

No digital competitor: Chile does not have native digital competitor banks, unlike Brazil, which has Nu, Inter, and others. The banks were able to roll out their own zero-fee, fully digital initiatives and payment acquisition projects. In the case of Banco de Chile, its digital service is called FAN, and its acquisition service is called B-Pago. If the low, middle class and small business target of digital accounts and small PoS devices are already covered, it will be much harder for digital banks to get in Chile.

Good efficiency, normal ROE: Efficiency ratios currently sit at 35/38%, but they are probably still influenced by high-rate, high-inflation income (net interest margins are closer to 5% versus a 4% pre-pandemic average). Historically, efficiency ratios have been closer to 42/45%, which is still pretty good.

ROE figures are not particularly impressive, 10/12% in the pre-pandemic period, jumping to 15% in the post-pandemic high net interest margin environment.

Valuation and thesis play: I don’t have a particular thesis on Chilean banking (I have not covered the other Chilean competitors like Itau, Scotiabank and BCI). On a general basis, banking benefits a lot from positive capital flows appreciating a currency, so a bank like BCH should be an interesting vehicle to express that view.

The company’s valuation is not super demanding at 7/8x earnings, but these earnings are still influenced by high-rates environment. They could easily move to 10/12x levels without a change in price. At 2x book with a historic ROE of 10/12% is not a screaming buy, but it’s an interesting name to follow.

Banco Santander Chile ($BSAC)

Santander Chile is pretty similar to Banco de Chile (this is not strange for banks, to be honest).

They have a similar market share in terms of assets and deposits, and their balance sheets are almost identical, with small variations. Santander is more exposed to mortgages (33% of assets), and less exposed to commercial (32% of assets). With more assets on mortgages, they also have higher exposure to inflation-adjusted assets (60% of loans).

It has a higher exposure to market financing (bonds and debt are 37% of liabilities). They basically have no exposure to USD debt as they have swapped foreign exchange bonds to CLP.

The efficiency of the bank is a few points worse than that of BCH. I generally get the read of a more ‘wasteful’ culture of nice offices and branches versus a more traditional and conservative BCH. For example, Santander converted ⅓ of its branches to co-work spaces, an idea that seems a little odd.

Santander’s valuation is a little higher than BCH, at 8/10x earnings.

Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile ($SQM)

Global lithium leader: According to its CAPEX plans, SQM will produce 300,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) by the end of 2025. This could be as much as 30% of global 2024 production (Benchmark). Approximately 60% of SQM’s production is done in Chile, with projects in Australia and China as well.

Low-cost producer: Even at 2024 cutthroat LCE prices ($11.5/kg on average), SQM generates 35% ex-D&A gross margins on lithium. This, combined with their size on the global market, puts a very large margin of safety on cycle-bottom profitability. If SQM has to abandon production, then other players will probably need to as well.

Other businesses: SQM has been a large mining company in Chile for way long than lithium has been a big driver of business. The company has leading positions in iodine salts (35% global market share, used for pharmaceuticals) and in potassium nitrates (40% market share, used for agriculture). With lithium prices as they are today, they represent about 50% of gross profits. Iodine in particular seems like a lower cyclicality business.

Manageable leverage: The company is levered, with $4.8 billion in debts versus $1.5 billion in cash. The debts have very attractive rates, on an effective cost of 4%, implying interest expenses of $200 million per year, compared to operating income of $1.2 billion on a TTM basis (with depressed lithium prices).

Lithium renegotiation process: SQM’s licenses for its lithium mines in Chile will end in 2030. The Chilean government has proposed to the company that it can maintain its licenses until 2060, but that in exchange it should allow the public copper company (Codelco) to become a shareholder in the mines.

The terms of the agreement have been disclosed (here), but the agreement has not yet been finished. Among other things, SQM will contribute its main lithium subsidiary in a merger with a Codelco subsidiary, forming a JV. Ownership will be 50/50, but the place Chairman will be given to Codelco. Until 2030, SQM will consolidate the JV, and after that Codelco will.

Between 2025-2030 the JV will maintain a 300k ton LCE quota and will pay the profit coming from 33k tons to Codelco (or an interest of 10% economical), with the remaining profits flowing to SQM. SQM will chose the CEO. After 2030, profits will be divided based on share ownership, and the CEO will probably be determined by Codelco.

Efficiency of the government in lithium: The question here is how efficient the government-ruled operations will be, as half of the profit will flow to SQM. Will the managers choose the best for the exploitation, or the best for the political interest? If it was for tax revenue alone, the government could have maintained a system of licenses with a sliding scale of taxes, as it works today. Having control implies other ideas.

Economics of lithium and its cycle: The lithium cycle will probably be determined by the economics of its supply. How expensive is it to expand lithium exploitation? How quickly can it be done? What is the percentage of variable costs on lithium extraction? The higher the CAPEX, the longer it takes, and the lower the weight of variable costs on total costs, the more violent the cycle movements can be. On the contrary, easily expanding production will put more pressure on producers, making the industry look more like agriculture or protein breeding, with large periods of down cycles and only occasional and short spikes in price.

Valuation is interesting enough but needs work on uncertainties: SQM is trading at close to or even less than 10x current earnings (without considering expansion plans via JVs in Australia). If one has a theory about cycle prices for lithium that implies the current situation is transitory, then it can be interesting for speculative purposes. Otherwise, more modelling is needed, specially about costs after the government takes control of the mines.

Latam ($LTM)

Largest LatAm airline: LatAm is by far the largest Latin American airline. Chile is only about 25% of its operations (in terms of planes). The company is also big in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and connecting the rest of the countries.

Post-bakruptcy financials: The company filed for Chapter 11 in 2020, leading to a recapitalization (its lenders became its current largest shareholders). This helped the current company quite a lot, because it was able to drop a lot of financial costs. Obviously, the previous shareholders were wipped out. Interestingly (or not) almost no one in the management team (Chairman, Board, C-suite) was changed after the restructuring.

Competitors didn’t bankrupt and are struggling: Latam largest competitors in Latin America, including Azul ($AZUL) and Gol ($GOLLQ), are deep in the red in the financial side because they are paying high rates for their leases and debts.

“Good” financial position: Airlines are not a bad business on an operating basis. Operating margins for Latam, Azul, Gol, and Avianca are all above 10%. Pre-tax ROAs (operating income over assets) are also good at close to the same figures.

The problem is financial, because interest rates can easily go well above 10%, and because some of the ownership cost is hidden below the operating line, in financial lease expenses (these expenses would go to D&A if the plane was owned, potentially showing unprofitable operations).

When an airline accumulates too much debt or leases, its ROA cannot cover its cost of debt, and it starts to go broke, just like it happened to Latam, and is happening to Azul and Gol.

Latam currently does not have this problem (its net interest/assets is only 4%). However, its interest is already 50% of operating income, so adding more debt or leases would be counter productive.

Potential to maintain the position: If the company does not expand aggressively using debt and expensive leases (challenging given the incentives at the interior of airlines), then it may be able to finance its way through profitability, and even acquire some of the assets of its competitors.

Valuation is interesting: Latam trades at 10x earnings. If the financial model is sustainable (i.e., in my opinion, not adding expensive debt or leases, and not hiding the cost of assets in financial lease expenses), then we could be talking of an interesting company to look at.

Embotelladora Andina ($AKO) and Compañías Cerveceras Unidas ($CCU)

Beverage manufacturers: Interestingly the two ADRs for the Chilean consumer sector are competitors in soft and alcohol beverages.

Andina is the licenssor of Coca-Cola products in Santiago metro (40% of Chilean population), half of Argentina (not including Buenos Aires), Paraguay, and parts of Brazil. The company also recently distributes some beers (Heineken in Brazil), and spirits, but their main business is soft-drinks.

CCU, on the other hand, is more focused on beer (the name of the company United Beer Brewer Companies), spirits, and wines. Its main markets are Chile and Argentina. In soft-drinks, it licenses Pepsi products, and Red Bull, as main lines. In beers, it licenses Heineken, Miller, and some others from AnBusch. It owns a few 10% brands in Argentina too. In wines it is not dominant either.

A story of two managements: Originally, CCU had much better margins than Andina, but the situation started to shift, even though both companies are exposed to similar geographic markets. Andina was able to maintain gross margins around 40% and operating margins around 12%, whereas CCU went from 55% to 40% gross, and from 20% to 7% operating. The shift started to happen in 2014, when Chile started to depreciate, and Argentina started to go crazy on inflation.

I compilled an analysis of the CCU’s and Andina’s MD&As for each year since 2014 (interesting work for GPT-o1, btw). The difference seems to be on cost most of the time. CCU complained every year that costs were running higher than pricing in its markets (from PET and aluminum in Chile, from inflation in general in Argentina). It seems it was unable to pass the price increases, or that it was worse at managing the company. Andina suffered the same cost setbacks, in both countries, but was able to come ahead, and match the costs via pricing, maintaining margins.

Another potential factor explaining the difference is CCU’s higher reliance on more discretionary categories like beer versus soft-drinks, or in the CAPEX invested in the competitive wine segment, which lost 10pp+ of EBIT margin since 2014.

Valuations are not super interesting: Andina trades at 12x+ earnings, and CCU at as much as 20x (15x on a recovery of margins scenario). I do not think they are so interesting, given the growth potential they have is more limited to GDP growth. There is not much more market to expand to, as their territories are based on licenses, and their own franchises are small.

Enel Chile ($ENIC)

Generation and distribution of electricity: Enel Chile (property of Enel SpA from Italy at 65% of shares), generates about 25% of Chile’s electricity. The company is also the licenssor of the distribution monopoly of most municipalities in Santiago metro. Previously it also managed the transmission concession, but it was required to divest those assets.

Challenging years: The last 5 years have been pretty bad for ENIC, for a few reasons.

First, they went into the pandemic with a heavy short energy position on the generation business. They obviously generate electricity, so having short electricity contracts is not bad per se. The problem is what happens if the gap cannot be filled with production at a time of high electricity prices. That is exactly what happened to them in 2021/22/23.

I have not understood completely whether the company had too much bad luck on the supply side, or if it was reckless on the sell-side, but several factors combined to generate a 10k GWh short position per year: decomission of coal plants, COVID pandemic delaying the construction and connection of renewables and droughts reducing the hydro capacity of the company (40/50% of generation) to 70% of average values. To make things worse, electricity became super expensive because other hydro generators were also short, and the Russia-Ukraine war made LNG imports much more expensive.

At the same time as this was hapenning, the Chilean government (first center-right then hard-left) started to enact regulations to shield consumers from higher electricity prices. In total it created three different 10 year funds (called PEC 1, 2, 3) to work as buffers from upstream to downstream prices. The first buffer was supposed to be self-financed (replenishing during cheap electricity, and draining during expensive electricity), but it was quickly drained completely, and it was still 2021. The funds number 2 and 3 were financed via government bonds that do not have an open market but can be refactored, something the company did, at some financial expense (not too terrible, but still a $20/40 million impact on earnings per year).

Finally, in distribution the rates of returns for the distribution service was reduced to 6% from 8% post-tax, and there have been delays in issuing the model cost of service for Enel to determine its mandated profitability. The 2020-2024 VAD (value added at distribution) has not yet been determined, and the 2024-2028 is still in the works.

Recovering and potentially interesting: The company is now recovering from all those hits, and planning for a more conservative outlook, in which it does not extend short electricity contracts, and looks to close the gap of production. It will invest mainly in renewables and battery to grow capacity closer to its structural short level.

The company has assumed pretty conservative scenarios until 2027, with hydro producing 30% less than it did in 2023, no expansion in sales, and no funds generated from the distribution service (basically break even on a cash basis between investments and cash flows).

Still, it trades at a P/E of 8/10x of those FY27 earnings, with a potential deep in 2025/26 because of hydro, and potential upside also provided by hydro. With gas coming more easily and cheaply from Argentina, the short risk is now much lower, but the company is still maintaining a cautious stance.

I have not understood the company’s core cost equations, to see how risky the company projections are, and whether or not there is upside.