Mexico is the prime candidate for benefiting from the nearshoring trend. It has a history of ever-increasing manufacturing integration with the US and several competitive advantages.

However, the country also faces challenges and the ever-present political risk of the Latin American economies. Despite the significant improvement in Mexico's fundamentals, the market has not repriced the valuation of Mexican companies. Investors have concentrated on industrial real estate but have left many other sectors unattended. Could they represent an opportunity?

This article introduces the nearshoring trend in Mexico, including whether the trend is real, advantages and disadvantages for Mexico, and which sectors could benefit.

As always, if you liked this article, please help me share it.

If this is the first time you are reading and would like to receive more introductions like this and other investment-related content, be sure to subscribe.

1- The basic nearshoring thesis

The thesis for Mexico’s opportunity in nearshoring is simple: a series of factors are driving supply chains nearer to the US. Mexico can capture market share from other exporting markets (mainly China) and attract investment from countries looking for closer access to the US market.

There are two main factors behind the nearshoring trend, both of them related to risks (and Mexico’s ability to reduce them). First, the competition and trade war between the US and China leads to the former losing competitiveness in the US market. Second, the post-pandemic realization that supply chains should not only be cheap but also resilient to war, climate, and other tail events.

In this context, Mexico has several competitive advantages: proximity, accumulated experience in manufacturing, a positive regulatory framework and collaborative politics, and low wages.

2 - How big is the opportunity?

In the short to midterm, the direct effect of nearshoring is an increase in Mexican manufacturing output. The sources agree that the potential for Mexican manufacturing moves the trendline from about 5% to 6% real yearly growth to a level of about 10%. This massive growth rate implies that Mexican manufacturing will double in the next 7 years.

Over the long term, the benefits of higher manufacturing activity should spill over to the rest of the economy via higher worker wages, gaining experience and competitiveness in global supply chains, and ancillary industries. While at the beginning the share of value added may be small (each dollar exported requires lots of imports), a bigger market should lead to more Mexican value added over the long term. BVVA believes nearshoring will only boost potential GDP by 0.5%, whereas the CAF posted a 2% boost estimate. The investment banks raise the figure to close to 3% in the top range, but they obviously have a bullish bias.

3- Mexico today, a manufacturing hub for the US

Since the 1960s, Mexico has been opening to trade, particularly with the US. The result has been the consistent growth of exports and trade as a percentage of GDP. Today, exports represent nearly 40% of Mexico’s GDP, compared to 20% for China and 10% for the US (World Bank).

Most of these exports are manufactured products, with transport equipment (cars, trucks, auto parts), electronic equipment (computers, telecommunications equipment) and machinery being the largest sectors. In 2023, manufacturing represented 90% of exports (OEC).

The US is the single most important market for Mexican exports (77%, OEC). We can say it is the only relevant market for Mexican products.

Most of the manufacturing and exporting activity is concentrated in the US-Mexico border states and the center of the country.

4- Mexico’s nearshoring advantages

As mentioned in section 1, Mexico has several competitive advantages: proximity, accumulated experience, a positive regulatory framework and collaborative politics, and low wages.

Proximity is simple to understand. Mexico is connected by land to the US, has access to both the Atlantic and the Pacific, shares a huge border, and a truck can be in any US city in less than a week, compared to a few weeks at least for a container from South East Asia.

Mexico also has accumulated experience in manufacturing. This is an intangible but important asset. The country has been offshoring US production for 60 years, so it has complex supply chains, prepared professionals (engineers, lawyers, accountants, etc.), experienced banks, and a supply of technically prepared labor force. Mexico ranks 25 in the Trade Economic Complexity Index, which measures how diversified and complex are a country’s exports (albeit without adjusting for imports). It also ranks 6th in terms of total STEM graduates per year (220 thousand in 2020). Manufacturing is not an on/off switch, you need the slow accumulation of experience that Mexico has been building and no other Latin American country has. This is particularly true for some supply chains (vehicles, electronics, machinery).

Mexico also has been solidifying an investment-inducing legal and political framework that provides legal security. The country has long been pushing for free trade with the US and other important countries in global supply chains (13 free trade agreements with 50 countries). It has maintained an independent central bank, an open capital account, and a market-defined exchange rate for decades. It offers lower taxes for manufacturing exports and imports (IMMEX program) and an asset-protective corporate structuring framework (shelter companies). Finally, the more ‘radical’ elements of its political class have shown pragmatism when dealing with the US, treating it as a partner and not an enemy.

Finally, Mexico’s manufacturing wages are low compared to China’s, and competitive with other Southeast Asian manufacturing hubs.

5- Challenges and caveats of the trend

Does the above mean Made in Mexico will replace all Made in China and that the country will enjoy 30 years of 8%+ growth? Probably not. A few negative factors weigh on the country: infrastructural bottlenecks, a way smaller scale than China, a protectionist US, and trade imbalances.

Starting with infrastructure, Mexico has three bottlenecks complicating the installation of more plants, particularly in the Northern regions. The first is electricity, with several regions having substantial deficits (particularly in the center) and others suffering from underinvested grids (particularly in the North). The second is water stress, again particularly vicious in the desertic Northern regions. Finally, Mexico’s highway and railroad system already shows bottlenecks in important areas like Monterrey. The main culprit behind these bottlenecks is chronic underinvestment in infrastructure (about 2% of GDP per year, excluding hydrocarbons). BBVA has a good report on this topic.

The second aspect is that Mexico’s markets are way less diversified and smaller than China’s, which means the manufacturing boom will be limited to the US and to specific industries. China has a much higher population, is closer to a much higher percentage of the world’s population, and has a much more diversified exports base (both in terms of products and destinations). This means that China’s manufacturers have advantages of scale, and a much more closely knit supply chain. Thinking of Mexico winning in areas outside of its current core competencies, particularly in markets outside of the US, seems difficult.

Another negative factor is that the US may increase protectionism against all actors, not only China. This question mark has to do with the US’ strategic alternatives. After the recognition that offshoring jobs to China strengthened a competitor and fueled a political wedge in the country, the US might prefer to isolate even further. However, Mexico can be an ally for protectionism and an enabler of the US manufacturing renaissance: it is not a real challenger to the US, whereas China clearly is, and it can provide the cheap labor in key areas needed to increase the system-wide competitiveness of North American manufacturing. Still, the risk of more protectionism is real.

Finally, Mexico cannot finance US trade deficits the way China did. For decades, China has been a trade surplus country, particularly against the US. Economic theory poses that if a country has a trade surplus, its currency should appreciate. However, China has arrested that process because it has a heavily intervened foreign currency market. China’s monetary authorities ‘overpay’ for US dollars and then relend those dollars in the US, therefore financing its trade partner. Mexico cannot do this because it has a free floating exchange rate. Its export competitiveness vis a vis the US should eventually even out via the exchange rate.

6- A positive trend in a negative cycle

The trade war with China started at least six years ago, and the COVID-19 supply chain disruptions happened three or four years ago. Therefore, we should already see the impact of nearshoring in Mexico’s figures. Indeed, this is the case across many areas. However, we should also consider that Mexico’s manufacturing exports are affected by a currently negative cycle in US discretionary income, too.

We can see the effects of nearshoring in many economic figures. Mexican manufacturing grew Mexico became the US' largest trading partner (imports and exports) in 2023. Mexican investment in equipment and nonresidential construction is already above its pre-pandemic trend. The same is true for Foreign Direct Investment. At least ten manufacturing sectors were growing above their pre-pandemic trend in 2023. Further, whereas aggregate manufacturing fell in the first half of 2024, the export-oriented sectors (mainly vehicles and electronics) continued growing at close to double-digit rates.

These positive readings should be tamed through the lens of the US consumer discretionary cycle. Mexico’s export manufacturing is geared toward discretionary consumer products (automobiles and electronics). For two years already, the US consumer has been challenged, and after the supply chain shortages of 2021/22, many industries have suffered from inventory gluts. Exports are growing despite, and not thanks to, the US economic cycle. The situation should improve dramatically if and when the US consumer recovers and when the inventory cycle turns positive. Mexico could present a leveraged opportunity to that cyclical turn.

7- Several industries look like opportunities for deeper dives

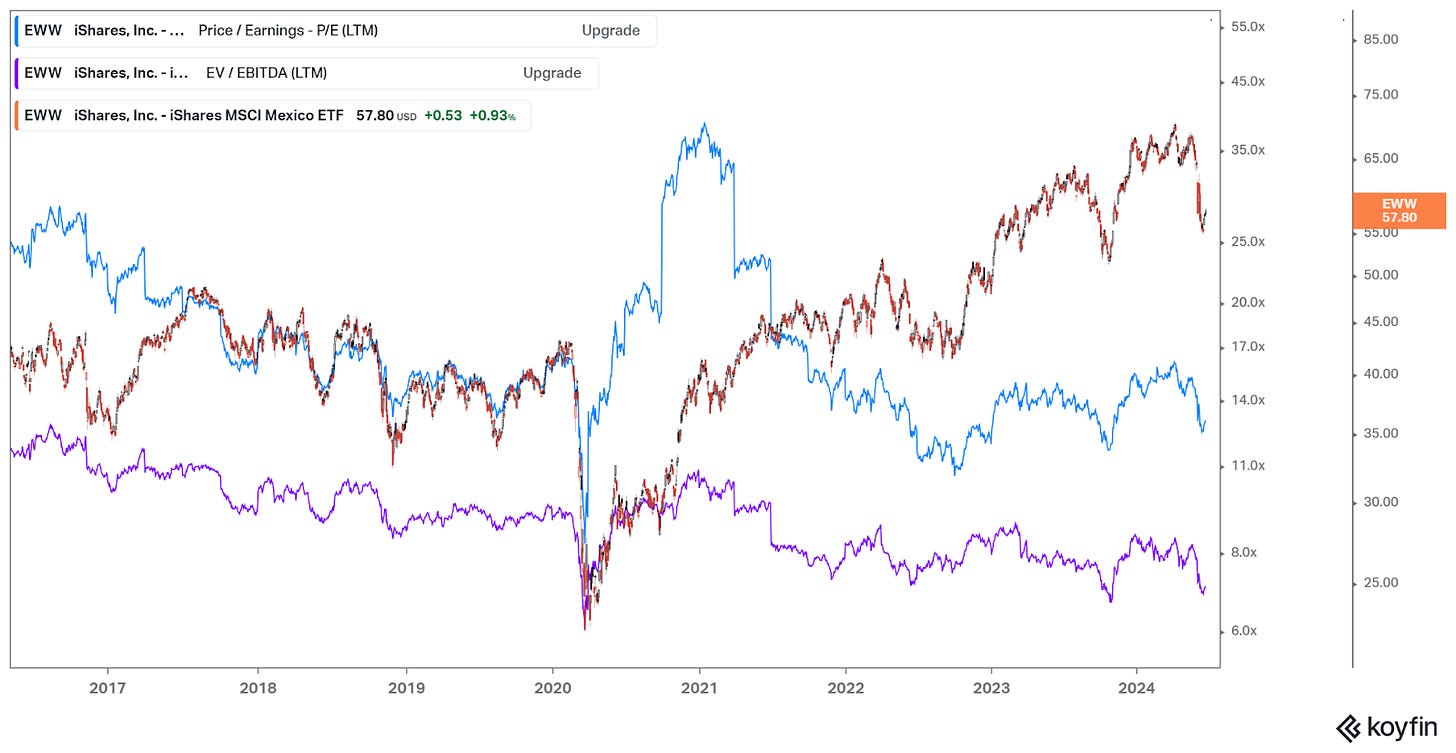

When we look at EWW, the Mexican stock market ETF, its valuation metrics have not meaningfully changed since 2018, when the trade war with China started, or since COVID, when the resilient supply chain trend started. Despite this, the ETF price is up close to 50%. This indicates that the gains posted by EWW between 2019 and today were generated by improving profits, not inflating valuations.

Unfortunately, there are few avenues to directly invest in manufacturers that may increase their US market share. The Mexican stock market is relatively small, with about 150 stocks, and manufacturing is not very represented. However, many sectors will benefit indirectly.

I have not run a deep dive through these sectors, but believe most of them can represent a good starting point for readers looking for underpriced opportunities.

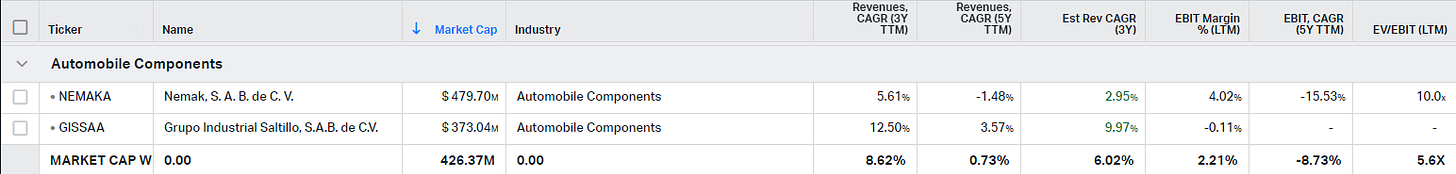

Automobile Components: The sector most directly benefited from nearshoring on the Mexican stock exchange. Mexico is the leading auto exporter to the US, and this dominance will only increase with nearshoring.

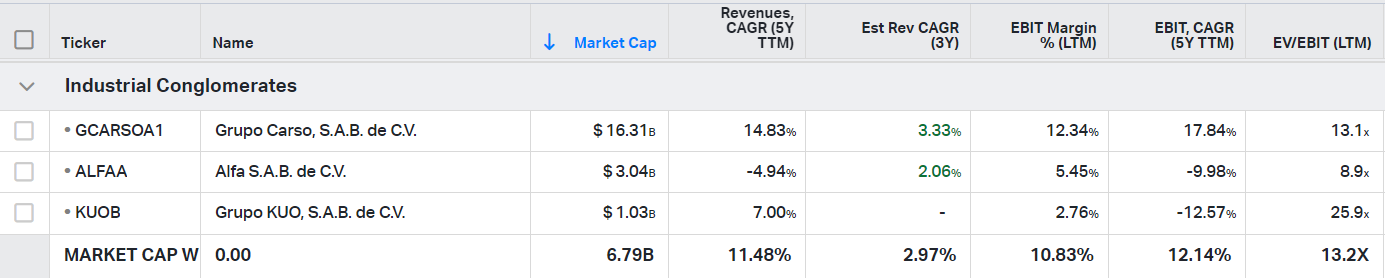

Industrial Conglomerates: The conglomerates are also directly exposed to nearshoring (for example Carso and KUO in vehicles, and Alfa in petrochemicals), but they are also diversified into the Mexican consumer and construction.

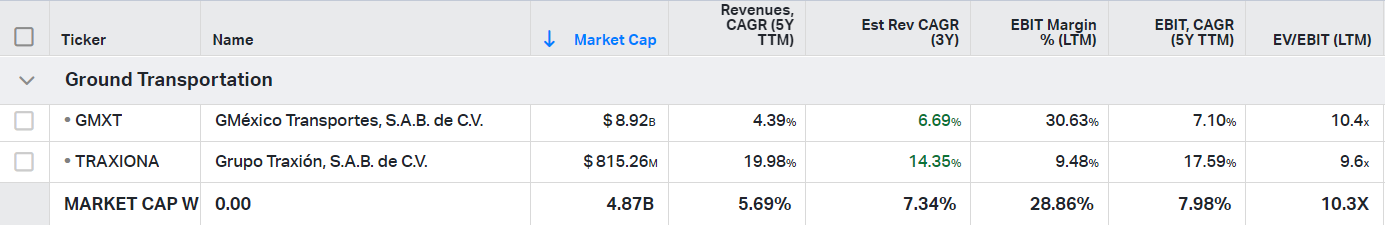

Ground Transportation: more than 70% of US-Mexico trade moves in trucks, and trucking companies on both sides of the border could benefit. This sector’s margins are volatile and competitive though.

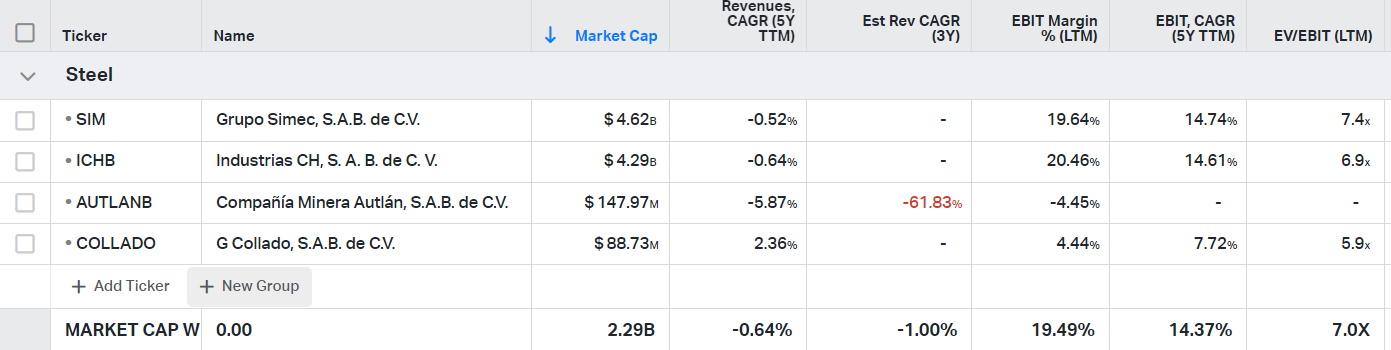

Steel, chemicals, and metals: These industries are indirect beneficiaries of the higher demand for end products (steel for automobiles, processed metals for electronics), leveraged on high CAPEX fixed investments.

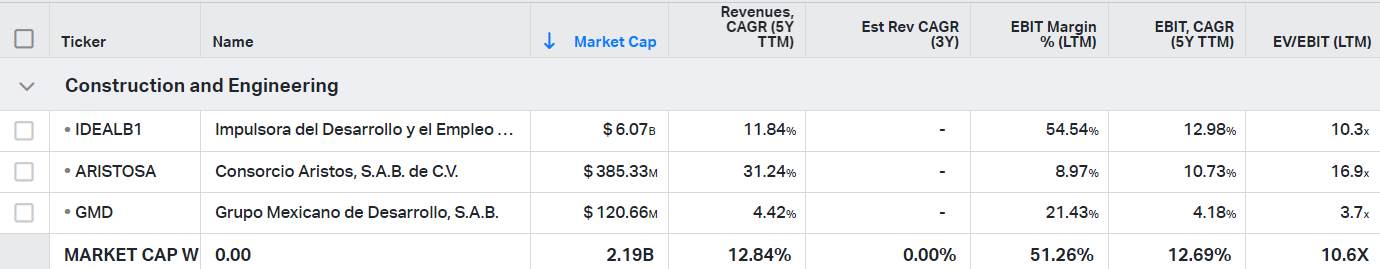

Infrastructure: One of the main challenges to Mexican manufacturing is the lack of infrastructure. China’s industrialization was cemented on roads, trains, airports, grids, pipelines, and industrial parks. These investments require cement, materials, and engineering.

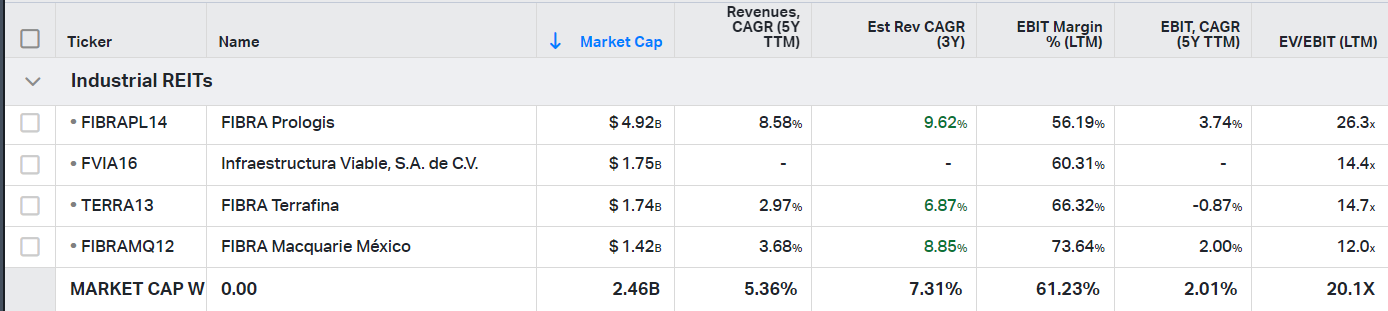

On top of the builders, a more leveraged play is the current infrastructure owners, like the airport operators or Industrial REITs.

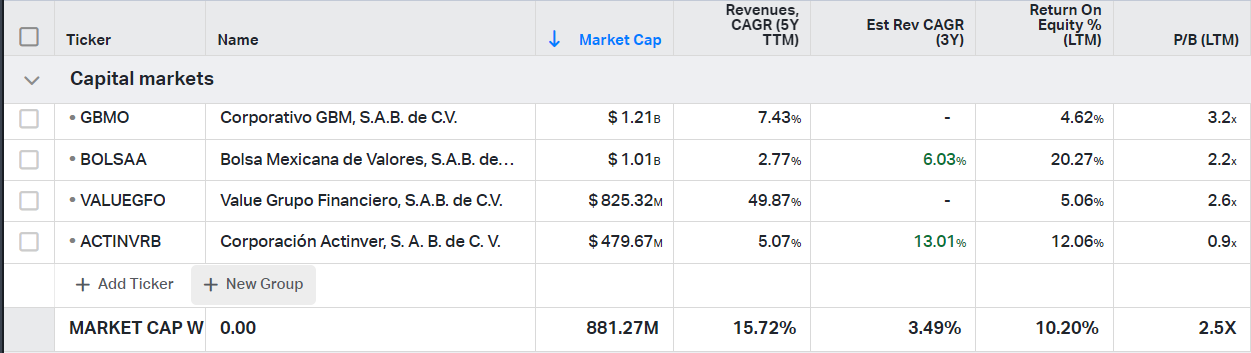

Banks and capital markets: The Mexican banks are already interesting because of historically high ROEs and growth rates. Nearshoring could give them a growth boost. The same is true for local investment banks and the Mexican Stock Exchange itself.

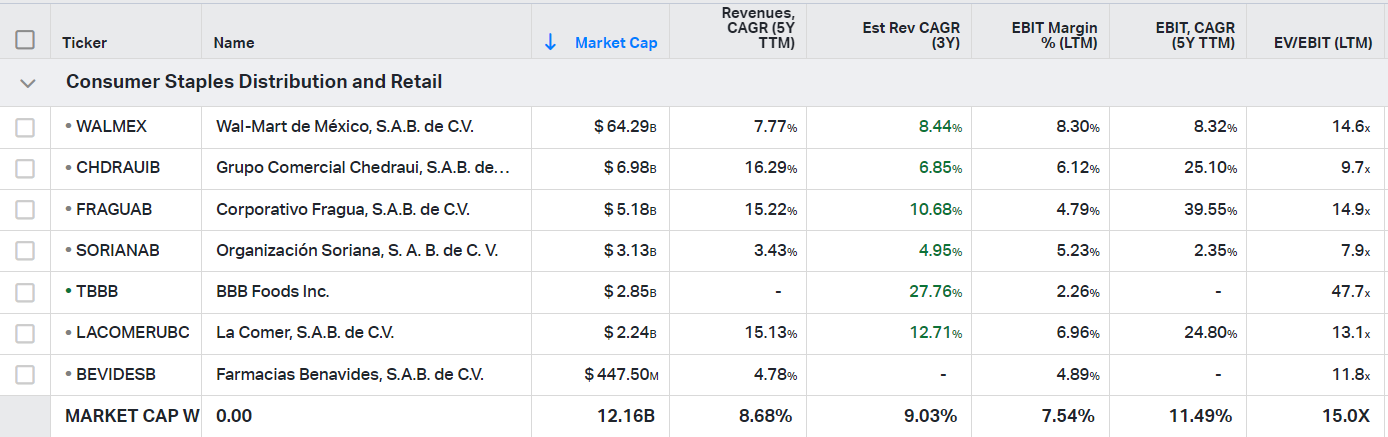

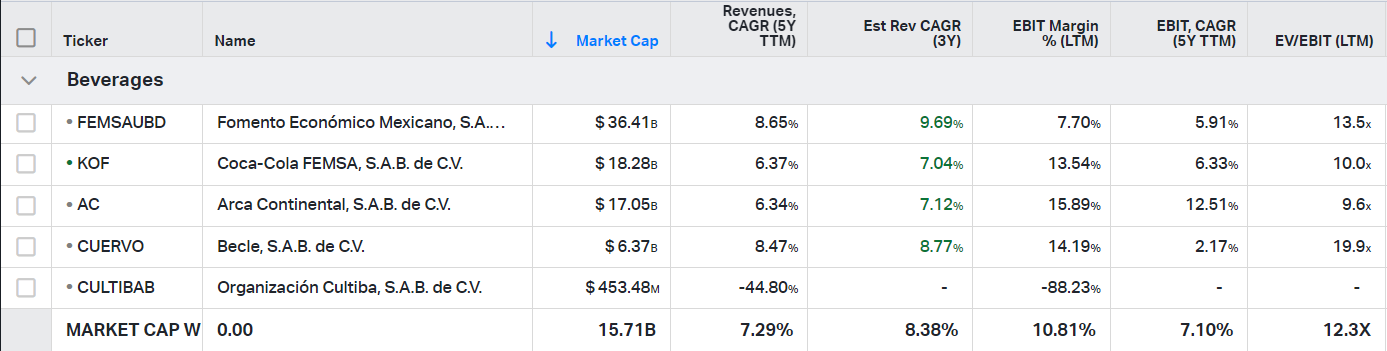

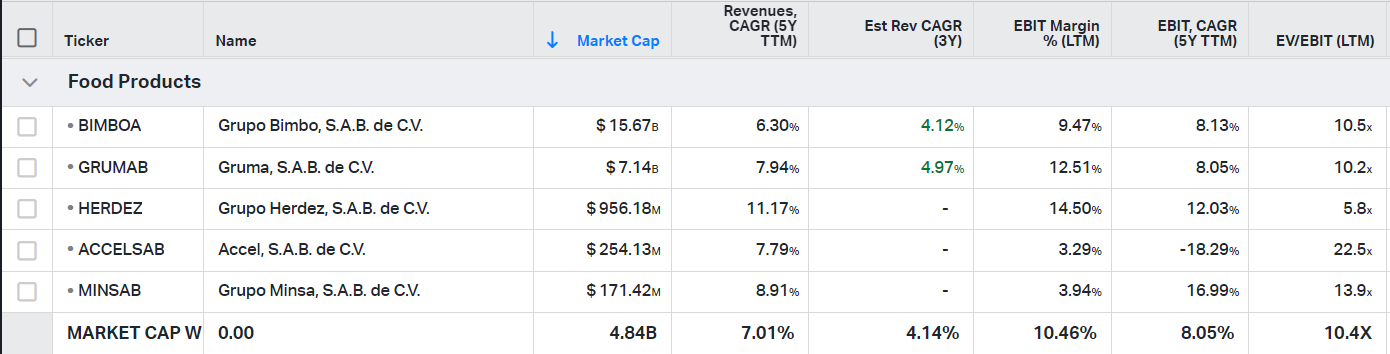

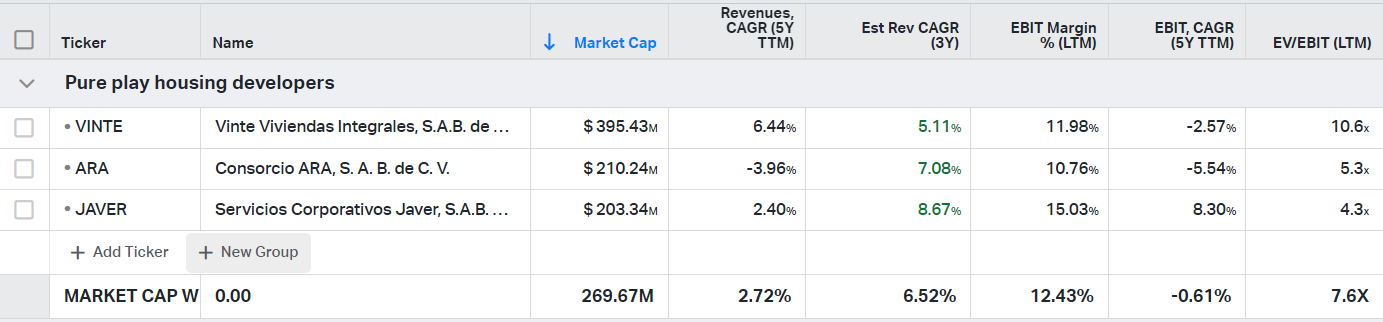

Consumer economy: With manufacturing representing 25% of jobs in the country and even higher in some areas like the North or Center, one could expect more manufacturing to raise income levels over time. Construction and professional workers should also benefit from this trends indirectly. Industries exposed to the Mexican consumer like retail, food products, and housing, could benefit, albeit over much longer time frames than the above industries.

Share and subscribe!

Hope you liked this article. If you did, sharing it is the best way to help me.

If this is the first time you are reading, don’t forget to subscribe to receive articles every two weeks. I have written about many other industries; you can learn more about them in the Index.