China’s Model: Doomsday or Escape Velocity?

Rethinking the Chinese investment-led model from the basics of business cycle theory.

Today, most financial news about China is gloomy. According to the market consensus view, the country has run into a crossroads, being too dependent on investment to grow. This excessive level of investment and supply-side stimulus have led to the saturation of its domestic market and to increasing protectionism from trading partners, unwilling to accommodate China’s production surpluses. As the investment boom requires a financial counterpart in the form of debt, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratios are approaching unsustainable levels, which may eventually lead to generalized deflation or a market crash.

When I first encountered this idea, it sounded incredibly contradictory, at least measured against the traditional capitalist values of austerity, investment, and industriousness. How could there be an excess of these? The Chinese deflation problem is particularly interesting because Chinese equities trade near or below GFC valuations, and the bear thesis on the country is a consensus view at this point. If I could find an alternative explanation—and if it proved to be accurate and supported by evidence—, then I could make money as a contrarian.

Propelled by intellectual curiosity and profit opportunity, I embarked on a journey to understand the problems of excess investment and deflation. This exploration led me to adopt a somewhat contrarian stance on the Chinese situation. I don’t believe the country is heading toward a market crash or that its investment-led model will hit significant obstacles in the mid-term. On the contrary, I think channeling surpluses towards investment will deepen China’s technological and productive advantages. However, there is a risk that if investment becomes too centralized, China could lose some of its economic dynamism and that the adjustments needed to accommodate consistent industrial deflation will prove challenging for its population. That said, the country does have alternatives if and when it decides to adjust its course.

As I explored this topic —much to my surprise— I found that this problem is so central to the modern economy that it generally requires political and not market consensus to be resolved. When the solution changes, societies and the whole world change with it. In fact, the ‘excess investment’ problem can, to some extent, explain the depressions of the 1700s and 1800s, colonialism and imperialism, the world wars and communism in the 1900s, the US rise to power, its potential decline, and the challenges China faces today. It touches on the credit cycle, international trade, Keynes, Lenin, von Mises, and even the beautiful cathedrals of Italy. It is a truly fascinating topic that will continue to have a lot of impact in the world of investing.

This article is an attempt at a coherent explanation of the deflation problem, the different ways in which it has been treated in history, and how the current iteration (the Chinese-led deflation) might be different from previous ones. I also toy with some potential takeaways for investors interested in Chinese equities. Above all, I hope to help the readers understand this fundamental economic problem better, spur some debate, and get my ass kicked by people flagging the holes in my theory.

Business and credit cycle basics

The problem of deflation stems from the business cycle, that is, the natural imbalance between demand and supply in the economy. In capitalism, the business cycle has the important function of regulating profits and losses among industries to move capital and resources from where they are less needed to where they are most needed. The business cycle is what makes prices change and capitalism such a wonderful wealth creation machine. Unfortunately, if left to its own devices, and especially if its force is multiplied by the credit cycle (the expansion and contraction of credit), the contractive portion of the cycle (called depression or deflation) can lead to significant social unrest, and even to the end of capitalism itself. This has led most countries to try to control the negative portion of the cycle. This section is a quick overview of how all that works.

The economic calculation problem. At the core, capitalism solves efficiently and morally the economic calculation problem: what to produce and how. Morally because it gives some decision power (private property) to all and efficiently because the profit motive leads to a self-improving decentralized allocation of resources.

The business cycle, a necessary evil. In order for the capitalist system to work, it requires a properly functioning business cycle. If companies in markets with excessive supply or insufficient demand did not generate losses and eventually go bankrupt, the system would not redirect its resources to the most profitable (needed) activities. The business cycle is what allows capitalism’s creative destruction process.

Further, because expanding production is generally a good thing for a capital owner, there is almost a guarantee that sooner or later, production will exceed demand, and some adjustment will be needed. If we add the credit cycle and the animal spirits, then we are guaranteed to have depression cycles from time to time.

But capitalism cannot survive a true depression. Since early in capitalist history, as soon as labor division was high enough so that people needed a wage to live, protracted depressions led to social chaos. The problem is that whereas for a capitalist or wealthy person, the negative portion of the cycle implies some wealth loss and headaches, for the wage-earners, unemployment means abject poverty and potentially death. The social chaos generated by a prolonged depression can eventually lead to revolutions and the toppling of the system. The Great Depression is the last historical example that if you allow the depression to continue indefinitely, what comes on the other side is not a more efficient capitalist society but rather an anti-capitalist society (communism, nazism, fascism, and the like).

‘Let them eat cake’ said Marie Antoinette, which is not very different from an anarcho capitalist call for ‘Let the banks collapse’ after GFC. Both lead to losing your head to an angry mob.

Governments manage the cycle. Because of the above, since the very beginning, governments have tried to ameliorate the cycle and avoid permanent or high unemployment.

In the origins of capitalism, the preoccupation with avoiding unemployment led to the ideologies of protectionism, mercantilism, and imperialism: governments should look for markets to expand production. Unfortunately, the finiteness of the world and competition between developed countries led to the two World Wars.

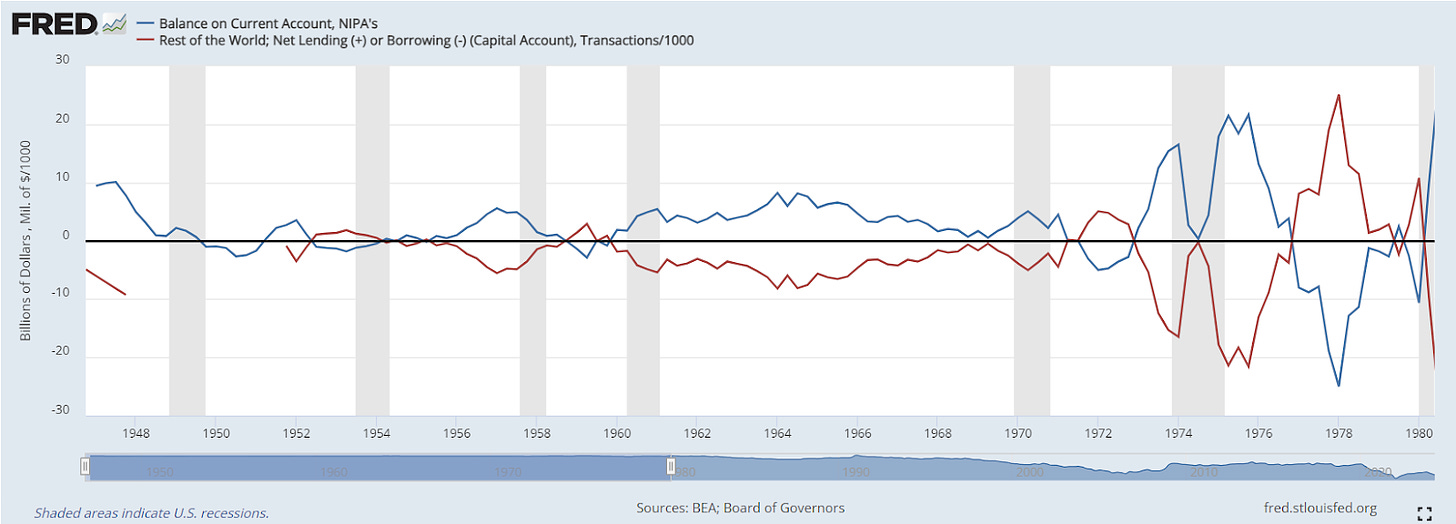

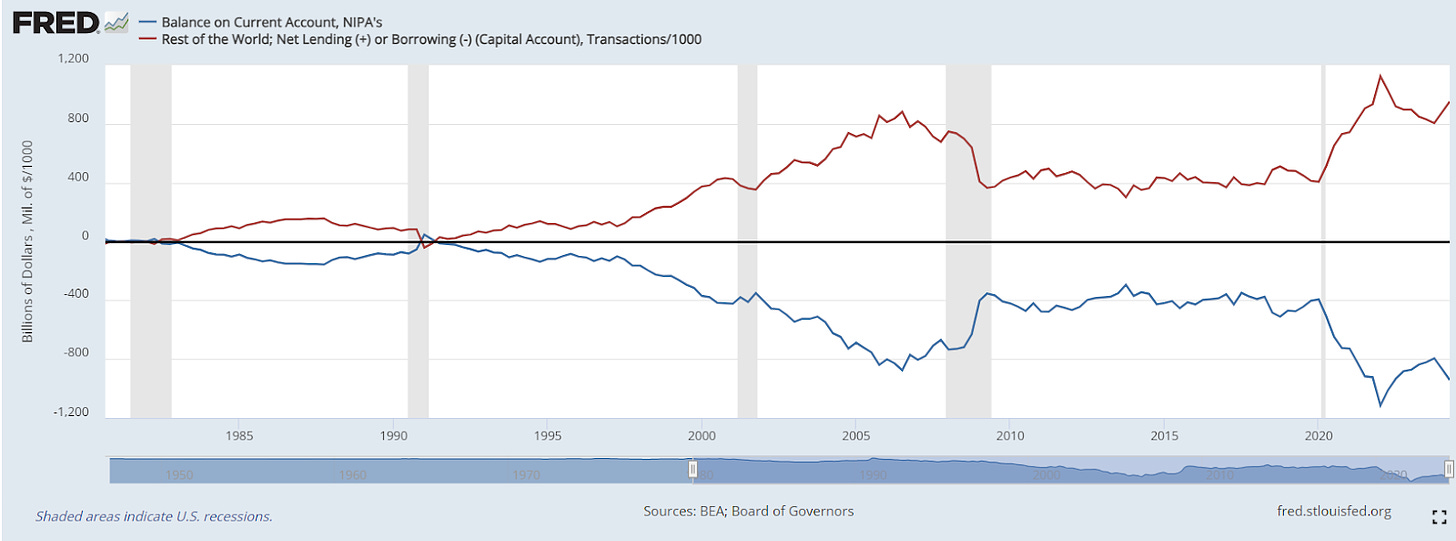

After WWII, the preferred mechanism for managing the domestic cycle became active fiscal policy, and after the 1980s, monetary policy. At the international level, the balance mechanism depended on some countries acting as lenders/exporters and others as borrowers/importers of excess supply (the US as lender/exporter and Europe as borrower between 1945-1975, and the US as borrower and Europe-Japan-China as lenders/exporters since then).

Between 1945-1980 the US carried a trade surplus, but it managed it internationally by financing (ROW net borrower in red above), the European and Asian countries rebuilding post WWII. That source of demand allowed the US to accommodate its excess production.

After the 1980s, the rest of the developed economies could not only not take US demand, but also needed to export their own excess. The US shifted to net importer (trade deficit in blue below) and net borrower (ROW net lender in red above).

Maintain the balance sheet fiction at all costs. In order to avoid a spiralization, the authorities have to maintain what I call the ‘balance sheet fiction’, that is, the fiction that assets are worth whatever the balance sheets of the agents (particularly the financial agents) say.

For example, if Company A goes bankrupt because the footwear market is down, then its loan in Bank B is also worthless, the same as the machines on which the loan is collateralized. Because the bank is heavily leveraged, it is probable that too many bad footwear loans also make the bank insolvent, so the deposit from Individual C is also worthless. The fiction that said Company A, Bank B, and Individual C had assets and not promises has fallen.

In the example above, the authorities have to find a way so that Company A and Bank B pay for their irresponsible actions, but without the situation going out of control. For example, the government may buy Company A’s loan from the Bank and eat the loss, giving the bank a secure loan in exchange (and maintaining the bank’s balance sheet fiction). Or it may let Bank B go under or get acquired by Bank D, while at the same time guaranteeing the deposit of Individual C. Or it may give money to Individual C (via stimulus checks or welfare) so that he can buy shoes from Company A.

Say’s Law, the monetary gap, and non-neutrality. As seen above, there are plenty of combinations available for policymakers to maintain the balance sheet fiction and sustain demand, but they generally entail creating a new financial asset. This is no accident. We need to make a small detour of economic thought to explain why.

Early in economic history, the understanding of depressions was based on Say’s Law (also known as market’s law): economies could not suffer a generalized lack of demand, because excess supply in one market necessarily implied a lack of supply in another, so that the demand for resources would always equal the supply of resources. This view was based on a barter economy in which the role of money and financial assets was limited.

Enter Keynes, with the finding that Say’s Law would not hold in a monetary economy. The reason is that between supply and demand, you necessarily have a monetary interstice during which some value could be lost or removed from the economy. For example, Worker A would generate $5 of value in his job, but would then spend only $4 and save $1, removing that $1 from the economy. Or, during a market crash, Factory B produced $100 of profit, but instead of investing it or giving it away as dividends, it would hoard it. This mechanism is ever more complex if we add the plethora of financial assets that serve as intermediaries between supply and demand (loans for consumption and investments, shares for companies to invest, etc.). Keynes then proposed that the state could fulfill the role of the lost demand via the creation of financial assets. These assets would not originally generate inflation because they would fill the gap of the demand lost.

But every solution comes at a cost, and Keynes’ remedy was no exception. By replacing individual decisions, the state was replacing the magic of the business cycle, and therefore making the economy lose some of its allocational efficiency and dynamism. The creation of financial assets was not a neutral act in the economy, it implied making allocational decisions. Save Bank A and not Bank B, and you’re favoring Stockholder A over B, and office-building owner A over B, and so on…

Non-neutrality is also why in Western economies, monetary action is preferred to fiscal action. In a fiscal measure, the government decides a lot: build a bridge here, give a check to these people, and support this industry with cheap credit. In a monetary measure, the government simply allows the creation of more money by the financial system, and that money flows to wherever the market sees fit.

A delicate balance. To summarize, the challenging job of the economic authorities of a developed country is how to allow some level of depressive cycle (particularly at the industry and company level), so that the allocational forces of capitalism continue working; while at the same time avoiding a spiralization of the process.

The China cycle

The economic consensus is that since at least the GFC, China has already reached a point of excess supply (or lack of demand), mainly from weaker import demand. Since then, government intervention has avoided a generalized crisis and a shrinking GDP, but at the expense of other imbalances, mainly more excess investment and the increase in debt.

Today, a lot of people expect some sort of collapse of the Chinese economy, while (few) others marvel at its impressive infrastructure and technological breakthroughs. How can both coexist?

In this section, we will address the Chinese cycle. First understanding what makes the Chinese economy special (or not). Second, I will propose a somewhat polemic theory that China can go on with its investment driven cycle for a long time, and that debt to GDP ratios are inconsequential. Then, I cover what are some ways in which the current model is causing trouble in the economy, and some ways it could potentially be resolved. Finally, some takeaways for investors interested in Chinese equities.

Chinese characteristics: what makes the Chinese cycle different?

Investment-led. In the West, demand is generally propelled by consumption, or indirectly via liquidity to financial markets (pushing up asset prices which in turn leads to investment or consumption via wealth effect).

In contrast, in China, demand is almost always supported by stimulus to investment (private or public via infrastructure). This is not a unique feature of China, rather it’s the classical East Asian investment-led model. China’s ratio of investment to GDP (which doesn’t even capture all forms of investment) is extremely high compared to any developed or large economy, and twice above the world’s median.

Debt financed. Investment generally needs debt in order to push demand (otherwise the investment has to come from savings which decrease consumption). Again, here China is among the highest in the world at close to 300% GDP (all non-financial debt over GDP). Most of this debt has been given to the private sector, by the state-controlled banking sector.

Financially closed. China has significant capital controls. The country’s debt is mostly denominated in RMB and is held by state-owned or state-controlled banks.

As we will see later, this makes a huge difference in how the credit cycle affects the business cycle. Whereas in the West, maintaining the credit cycle is complex because most financial assets are traded in markets between private counterparts, in China the assets are mostly held by public institutions. Maintaining the balance sheet fiction is much easier without a dynamic price discovery mechanism.

Confucianism. East Asian societies are more hierarchical, tolerant of repression, and responsibility-oriented. This, in my opinion, allows the countries to sustain higher levels of unemployment and economic adjustment without suffering political crises. The accusatory finger is generally pointed at China’s political system, but observers of South Korea, Japan, or Singapore know that Chinese authoritarianism is not a sui generis animal, but rather a variation of Confucianist societies.

China’s investment model won’t collapse.

Today’s consensus in financial markets is that China’s investment-led cycle is unsustainable and that the country should propel consumption instead of investment. For example, the country’s stock indexes trade at valuations not seen since the depth of the GFC. Let us see why this is and whether we can have a counterargument.

Self-repeating. The problem with an investment-sustained cycle is that it tends to worsen itself. The reason is that investment increases the country's productive capacity, and therefore, supply will be even higher in the future. If demand continues to be low, then more support will be needed, which, if it goes to investment, will further the cycle even more. The solution to such a cycle will need to be an external increase in demand (for example, higher exports or more confidence in the economy, leading consumers to use more of their savings).

Consistent deflation. As capital increases in an industry, its return decreases and eventually becomes negative, which means some industries will have deflationary pressure. This has happened in industry after industry in China. The most important recent examples are energy technologies and processed raw materials like steel (real estate is not an example because the deflation in real estate comes from removing demand support, not from pushing supply too much).

Deteriorating balance sheets. Because the value of a piece of capital (say a factory, a piece of equity, or a piece of debt) is directly related to its returns, then decreasing returns on capital make all assets less valuable. Therefore, the balance sheets of the companies in deflationary industries become challenged, as do the loans to those companies, the banks holding those loans, etc. By definition, if an investment is made in an industry with negative returns, it will not be recovered, and as we will see below, it can be treated as consumption even though it remains in a balance sheet.

Investment is a balance sheet fiction. In the realm of production, investment and consumption are the same thing. Once the resources have been used, they cannot be recovered in any case.

An example is important here. If 100 masons build a bridge, it is an investment. If they build a temple, it is consumption. In both cases, the 100 masons’ hours are gone (with the materials used). The difference is that in the first case, the bridge will remain in someone’s balance sheet.

From the financial perspective, investments have to generate a return to remain as balance sheet assets. Because excess investment kills the returns, the balance sheets are unsustainable. However, from the production perspective, there is no difference in whether an asset is maintained on a balance sheet or extinguished via consumption.

This means that, from the production perspective, if China simply labeled all of its investments as consumption and removed those assets from the banks' balance sheets, there would be no sustainability problem, and no debt problem. We would simply see the country’s monetization via government fiscal deficit.

If, rather than constructing more apartments and factories than global demand justifies, China were to invest its productive resources in building structures like Italian cathedrals —such as the Duomo in Florence—, its economy would be ‘sustainable’.

China is best prepared to maintain the fiction. What I described above, although sounds strange, is exactly what China does. The country determines that it wants to push investment into some industries and commands banks to lend heavily to those industries. When the industries become overcapitalized, and deflation and bankruptcies start to rise, someone either absorbs the loss via a write-off or leaves the asset as is. China can pull this off indefinitely because its financial system is closed and state-run.

This is also the reason why there will be no market or debt crash in China, even if the country reaches 1,000% debt to GDP. The debts don’t need to be paid in order to sustain future demand because the assets are understood as already consumed.

The problem is allocation efficiency

If it was that simple, then China would have found the road to economic growth forever. Unfortunately, China’s model comes with setbacks, that although will probably not cripple the country’s economy, will reduce the economy’s dynamism.

Remember from the first section that capitalism solves the economic calculation problem by giving profits to the people that find how to produce what others want, whereas it sends the ones that don’t produce what is needed to bankruptcy. This is why allowing the business cycle to progress is very necessary for an economy to remain dynamic and efficient.

In the Western model of supporting demand, it’s still private agents that make decisions. When people receive stimulus money, they decide what they want to buy, picking winners and losers. When liquidity is injected into capital markets, private agents in those markets decide what to invest in and pay for the costs. There have been bailouts, but these are not the norm.

In the Chinese case, the private sector cannot make these decisions, or increasingly less so. To begin with, the model is not predicated on supporting consumption, meaning that consumers don’t get to make those decisions. In addition, investment is channeled to certain industries not alone or mainly by the profit motive, but rather by the availability of credit, which is controlled or guided by the state.

So the Chinese problem is not that investment is unsustainable, because it is not, as long as they produce surpluses (more on this later). The problem is that in order to continue investing in overallocated industries, they diminish the power of the private sector, and with that, they kind of kill the golden goose that produced those surpluses in the first place.

The real limit is maintaining the surplus. When countries continually push demand (of consumption or investment), they start to run into budget constraints. For example, country A has excess orange production, so they subsidize oranges, but that leads to a deficit of fertilizers, which the country does not produce.

The way these budget constraints show up in the economies is via trade deficits. Undeveloped economies quickly run into trade deficits, lack of reserve currency, and inflation as soon as they start to apply demand support measures. The developed economies, in contrast, can sustain higher deficits because the world is willing to finance them, theoretically forever. In fact, the countries that today absorb excess production from other countries (like the US, UK, Canada), can only do that for so long because their currencies are reserve currencies. If the USD was not THE reserve currency, the US model would have needed a demand shrinking adjustment a long time ago.

The same could happen to China, because it is not an autarkic country. If it continues to invest in industries or resources that do not generate a sufficient return, it may start to demand too much of the world’s resources. This would eventually lead to a trade deficit. Without a reserve currency, China would not be able to sustain its trade deficit for too long before needing to adjust to a lower level of demand. An additional risk related to this is the world curtailing Chinese exports via protectionism.

The adjustment is painful and depressing. Even if the government can manage the defaults generated by deflation in several industries while channeling investments to new ones, the adjustment process remains painful. Workers in consolidating industries need to find other jobs, entrepreneurs see their companies fail, and students in previously sought-after areas find no jobs. This leads to a lack of confidence in the economy, something that is evident from China’s consumer and business confidence indexes.

Although painful, the fact that China’s industries adjust when they reach overcapacity is actually a positive. If the failing companies were allowed to continue operating as zombies, the country would lose its dynamism much faster and may reach budget constraints.

Workarounds

Are there ways in which China can escape this problem?

Decentralization inside a centralized system. China is also unique in that its statehood has been very decentralized, not only today but since antiquity. Anti-China propaganda wants to picture a country run by a single man or a massive central bureaucracy, akin to that of the Soviet Union, when in reality, the Chinese political and economic system has made great use of internal competition. China may reach a balance between a system that requires significant intervention to maintain the balance sheet fiction, but where the incentives for matching demand and supply still exist. For example, the country could push for excess investment in certain industries, but then push for consolidation and allow only the most efficient players to survive.

A new Marshall plan. If China currently solves its demand imbalance problem by subsidizing credit to domestic investment, there’s nothing stopping it from doing the same abroad. The country could lend to underdeveloped countries for them to buy capital and consumption goods from them. Eventually, if those lendings pay off, the better, but if they don’t, the loans can be written off, because that doesn’t really matter, just like investment.

A technological revolution. I think there is some belief in the country that with sufficient investment, China will be able to breakthrough some technological revolution and create an ocean of domestic and foreign demand. New technologies also provide the possibility to continue investing, by creating new industries hungry of capital. This strategy may work in some areas, like energy technologies, because it helps China reduce imports and loosen budget constraints. However, the strategy has a fatal flaw, and is that China’s problem is not that its products are not needed, or desired, or even the cheapest and best. China’s problem is that the rest of the World cannot keep pace with it, producing in order to demand from it. If China suddenly invented the liquid elixir of life, it would not change the fact that the rest of the World cannot buy it in the quantities that China needs.

Shrink the GDP without a crisis. Interestingly, because China focuses so much on investment, it can decrease demand without decreasing consumption, which is a great thing in order to maintain social stability. This is very different from the situation of the Western economies, in which an adjustment in demand to match supply caused by a budget-constrain has to come from a decrease in consumption, simply because it makes such a big part of the economy.

However, I think China will not follow this route unless it is faced with a budget-constrain like a trade deficit or that it believes the level of state intervention has reached an excessive point. The reason is that China could have decided to go the consumption route in the past and it decided not to do so. I think it has decided to continue investing because it wants to develop its productive capacities in manufacturing and technology before fulfilling other needs (like consumption).

Shift to consumption. A similar solution to the above, implies reducing the surplus used in investment and sending it to consumption. For example, direct more credit to consumption instead of investment, or apply higher taxes to corporations to reduce them to households, provide higher welfare services, healthcare, etc. All of this would cause the economy to consume more of the surplus it generates, making capital less abundant, therefore generating higher returns, and making for a more ‘balanced’ economy. Again, I don’t think the Chinese authorities ignore this, it is just that they don’t think the country is in that stage of development yet, they want to continue pushing the production path.

Takeaways for investors

If what I propose above is true (or truish, always leading with the big uncertainty that is the economy and society), then as investors considering China, we can take a few lessons:

China will not crash. The country is using its surplus production to fund investment, which in turn generates even more excess production. The surplus is monetized via bank lending, instead of simply being written down as ‘investment-consumption’, but represents no risk to the system. If eventually the loans were written off in an orderly fashion, production could continue. China’s true Achilles heel is its trade balance, not the level of internal leverage.

But what about real estate? That is a different story because instead of the banks (i.e. the state) being the final lender/investor, households were driven to invest in an industry with deflationary tendencies. This was a mistake, because it led to economic fear and a reduction in consumption, which is affecting the economy. The same dynamic does not need to happen if the investments made in deflationary industries are not financed by the households but via credit (i.e. monetization).

China will advance technologically at leaps and bounds. I think the whole Chinese thesis is not to invest in order to save a market crash or avoid a deleveraging, not even to keep the GDP print, because that is not needed to maintain the standard of living of the population. Rather, the authorities of the country want to increase capital as much as possible to gain an impressive technological and productive edge, and use that as a form of soft power. We already see many of those examples in the form of massive infrastructure and technological wonders. Shrinking investment would mean to lose an impressive advantage in the form of massive resources dedicated to manufacturing, science, and technology.

Secular tailwinds in services and consumption. Even if China continues with its investment-led model, consumption and service industries will do well. The reason is that, even if consumption as a percentage of GDP remains constant, the capital stock per capita in China will continue to grow. As a result, productivity per worker and real consumption per capita will also increase. In addition, if the government decides to shift towards higher consumption, services and consumption companies will benefit.

Soft barriers to entry and scarce resources are also valuable. In an economy where real production is growing massively and consistently, other scarce resources become exponentially more valuable. Workers are one example, with their real income increasing with more capital per capita. This makes the consumption and services industries desirable (as explained above). There are probably other scarce resources, potentially things like brands, licenses, access to specialized human resources, natural resources, etc. These scarce resources will grow in value against the rest of things that can be manufactured.

Capital-heavy industries will tend to deflate. Any industry that can receive capital will receive capital, simply because it is an avenue to generate demand. This means that any industry that requires capital will have excess supply and deflationary tendencies, and is, therefore, not a good place to seek investment opportunities.

Banks are key enablers. It is clear that banks play a huge role in the Chinese economy, with their market steadily expanding due to the need for bank credit to monetize the excess production that otherwise would not find demand. In this context, the banking sector could see substantial growth, and some banks may secure favorable spreads. However, if the theory of ‘decentralization inside a central system’ is valid, banks in China could still face controlled bankruptcies, meaning they are not immune to risk. That said, systemically important banks may be allowed to recycle their bad loans at the expense of the central government, avoiding large losses. While I’m not entirely certain about this scenario, I believe it's a valuable topic to explore.

Conclusions and further reads

The goal of this article is to spark debate and get my ass kicked by more informed fellas. I am not politically inclined, rather I believe this is a very interesting issue with international impact on markets, and potential opportunities right now. Each of the topics in the article could have been expanded into more detail, but I decided to keep it synthetic because of time/space reasons.

There are a few books and authors that have formed my opinion on this matter:

Ludwig von Mises theories about the calculation problem, and about the disequilibrium inherent in any system shaped how I see economic problems. Human Action remains the best book about economy that I’ve ever read and forms the basis of this article.

J.M. Keynes is the first economist that understood the problem of deflation and lack of demand seriously, and killed the previously untouchable ‘Say’s Law’. I’ve never read his General Theory, but a lot of his ideas entered my head vicariously.

Ray Dalio’s discussion about Deflation in his magnific book ‘Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises’ presents the deflation mechanism, the different types, and how to avoid them.

I don’t think there’s anyone that understand the implications of the Chinese situation better than Michael Pettis. His book ‘Trade Wars Are Class Wars’ is a great description of how Chinese (and previously Japanese, German or US) excess production affects the international order. His current reads on China in Twitter and his blog on the Carnegie Endowment are great too.

‘Making Sense of China’s Economy’ by Tao Wang is a fantastic overview of the whole Chinese economy, covering areas like urbanization, industrialization, investment, taxes, welfare, politics, taxation, etc.

As always, if you liked this article, please subscribe. The best way to help me continue writing is to share this article with other people.