Brazilian Banks Primer

A guide to the Brazilian banking sector, with industry characteristics, analysis of incumbents vs digital bank competition, and analysis valuation

In the Brazilian Stocks Primer, I said that many Brazilian industries are oligopolistic. This allows for higher profits and returns on equity for most participants. There is no better example of this than Banking.

The Brazilian banks are considered among the most profitable in the world, with returns on equity hovering above 15% for extended periods. They have done well across several regimes, including the GFC and the Brazilian recession, high and low rates, and with both sides of the political spectrum in the government. Brazilian banking is highly concentrated, with the Big 5 names accumulating more than 80% of deposits. Some of these super profitable banks are trading below a P/B of 1x despite posting 20% ROEs and 7% 10-year median asset growth rates.

However, a set of fast-growing digital banks is challenging this landscape. They promise better services at a lower cost. Thanks to their leaner structure, they can potentially compete with lower rates. The banks are responding with massive investments in digitalization and restructuring their physical operations, but the question remains: will the new competition permanently depress the industry returns?

This article presents a primer on the Brazilian banking industry, its characteristics, and how to model its future returns. It also covers the thesis behind the digital bank and what I believe are its limitations. Finally, we put everything together into a simple long-term return model to think about asset growth, ROE, multiples, and the exchange rate in the future.

As always, if you liked this primer, please share it with colleagues and friends, it makes a world of difference to me. Also, if you would like to receive more articles like this in the future, be sure to subscribe.

Index

Industry level characteristics

Participants

High Profitability

Heavy Weight of the State on the Credit Markets

Historically Positive Real Interest Rates

Effects of the Monetary Rate on Profitability

Credit Income Sources and Market Share

Importance of Service Revenue

Beware of the Exchange Rate

Digital Banks versus Incumbents

The Bull Thesis on the Digital Banks

The Bear Thesis on the Incumbent Banks

Commoditization and Digitalization

Principality and Competition

Prices and Opportunities

Book and Asset Growth

Returns on Equity

Multiples

Conclusions (and exchange rates)

1. Industry Level Characteristics

1.1. Participants

The banking industry is divided into three main segments: the big 5, the mid banks, and the digital banks (and their cousins the payment processors).

The Big 5: Itaú, Banco do Brasil, Caixa Economica Federal, Bradesco, and Santander Brasil*. They concentrate the majority of deposits and clients. These banks dominate in retail credit activities like personal loans, credit cards, mortgages and vehicles. They are also very important in government financing activities. All of them are publicly traded and have ADRs (with the exception of Caixa):

Itaú: the largest bank by assets. It has the first or second position in most retail categories (second place in mortgages but way below Caixa) and also big participation in corporate and SMEs lending.

Banco do Brasil: mixed private-public ownership. The bank absolutely dominates in agricultural credit. Its retail operations are less developed, although it has a strong position in civil servants.

Caixa Economica Federal: government-owned but ‘independently managed’. More than 50% of the mortgage market, with a strong boost from publicly-subsidized credit.

Bradesco: The largest bank back in the day and one of the most challenged by digital banks because it has a larger stake in low and mid-income retail clients. It is also strong in SME credit and has a big insurance operation.

Santander Brasil: higher retail orientation than the rest, and leader in vehicle financing. Its corporate operations are more concentrated on SMEs. Also among the most challenged by digital banks.

The Mid Banks: In addition to the big five, Brazil has a few dozen banks operating with a more niche or regional focus. We will not cover these in detail in this primer, as most of them are inaccessible as ADRs.

The Digital Banks: Nu and Inter are the main examples (both traded as ADRs). These banks don’t have much of a physical operation and concentrate fully on retail. They became strong by providing payment processing services to small businesses and being the first to offer digital payments. Their strength is their relatively inexpensive funding cost and lower service cost. Their credit focus is on credit card receivables and small personal loans, and have a generally worse credit profile than the Big 5. Their size is small compared to the big banks, but they are growing rapidly.

The digital banks are generally mixed with another fintech category, the Payment Processors. The name digital bank or neobank is used interchangeably for both. According to the Brazilian Central Bank (BACEN), payment processors can provide payment services and issue credit cards (for due payment) but cannot offer credit or pay for deposits. This is an important mid-term distinction because they compete aggressively with banks for funding (attracting cheap revolving deposits) but cannot fully compete in the credit arena. Of course, processors can become banks by receiving the appropriate authorizations, but this is not easy. A recent survey found 72 payment processors against only 9 fully fledged digital banks (further, no new digital bank license since 2021).

* Funny note: in Portuguese Brazil is written Brasil and the Brazilians made a funny commercial about this for the America Football Cup.

1.2 High Profitability

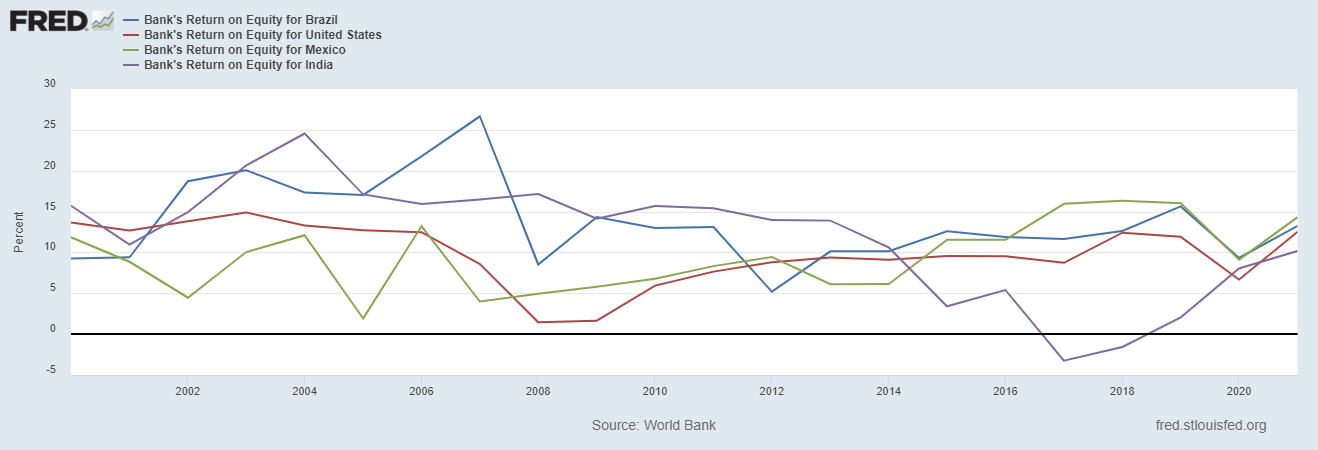

The banking industry is super profitable. Brazil’s industry-level returns are comparable to those in other emerging (India) or LatAm (Mexico) markets and higher than those in the US. This is consistent with risk-return theory, as less developed markets should offer higher returns to attract equity.

However, whereas both Mexico's and India's returns have cycled, Brazilian returns have been much more stable. We have to remember that Brazil’s economy slumped in the early 2010s after the commodity bear market started and that the country suffered a big recession between 2014 and 2016. Despite this, returns did not suffer much during that period.

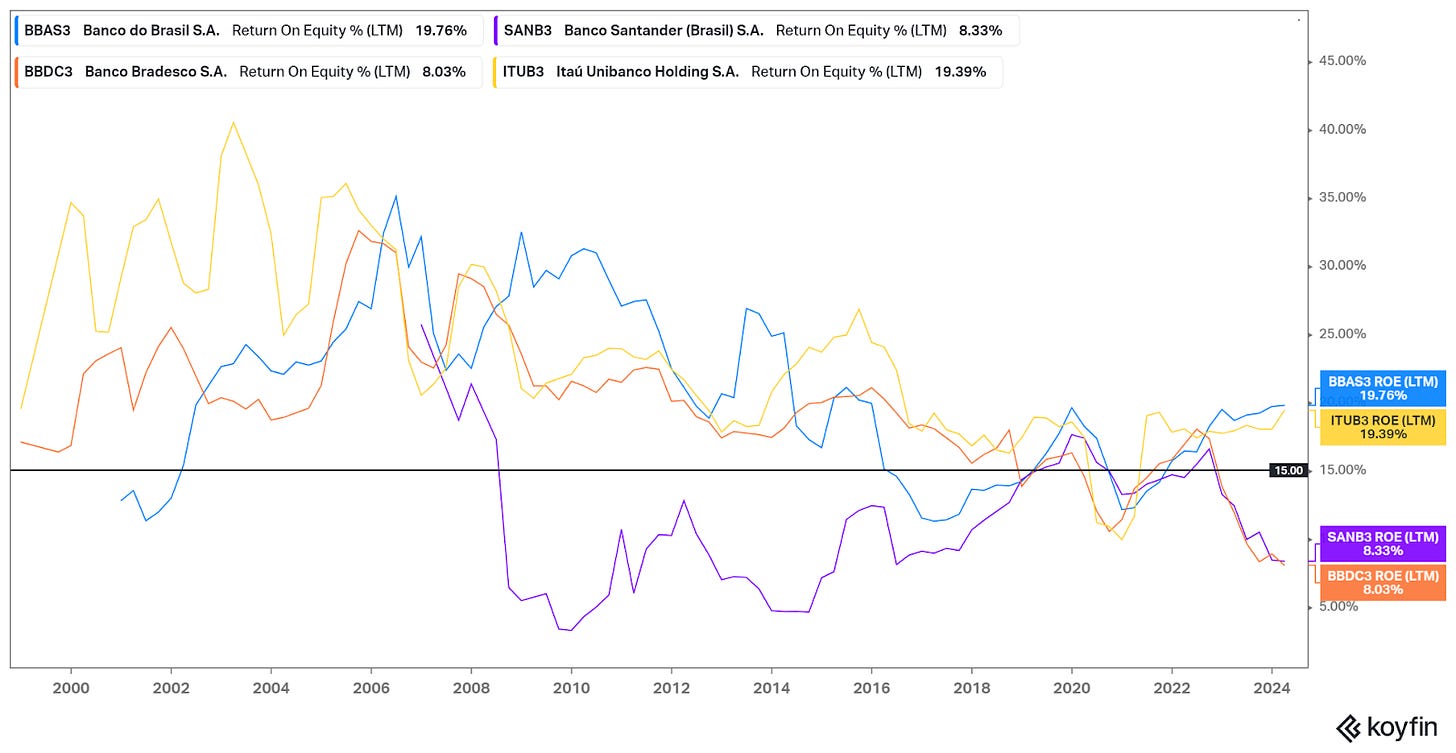

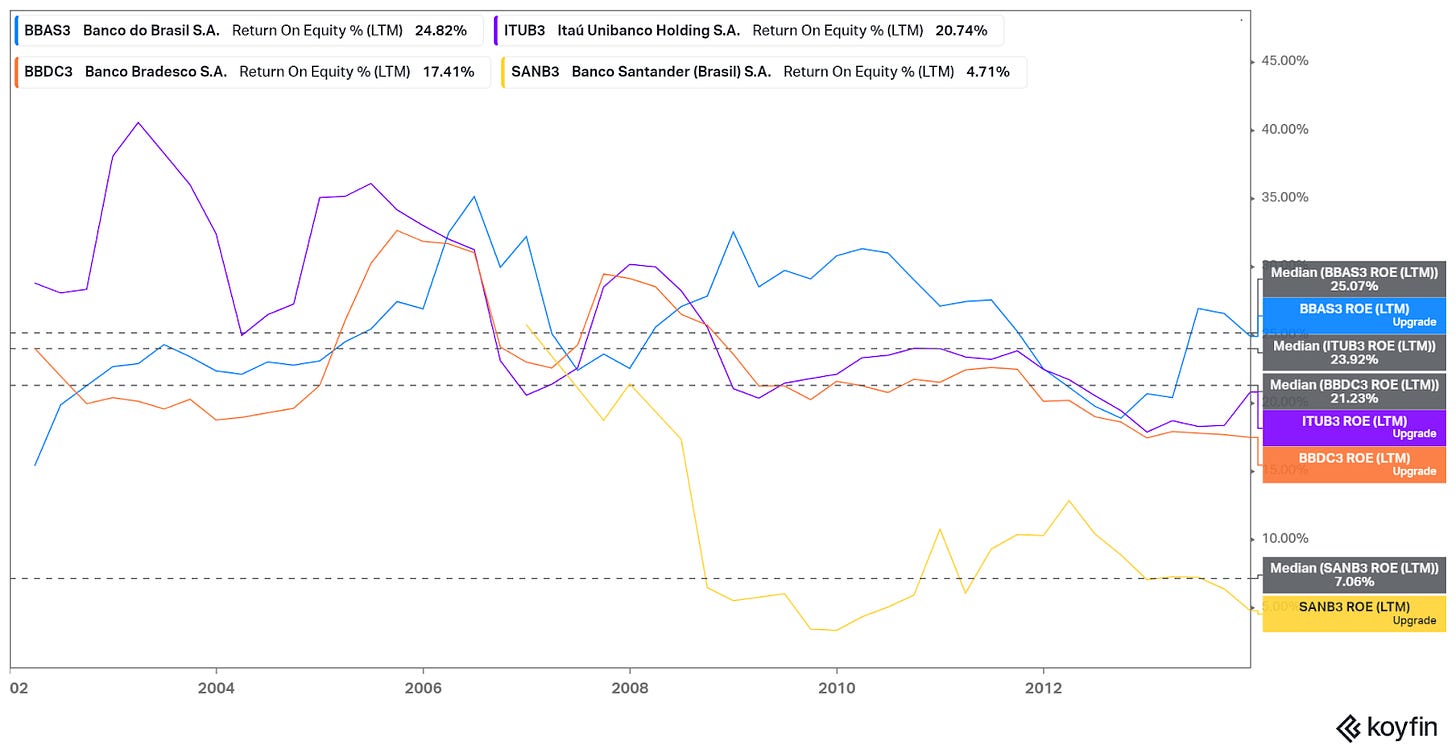

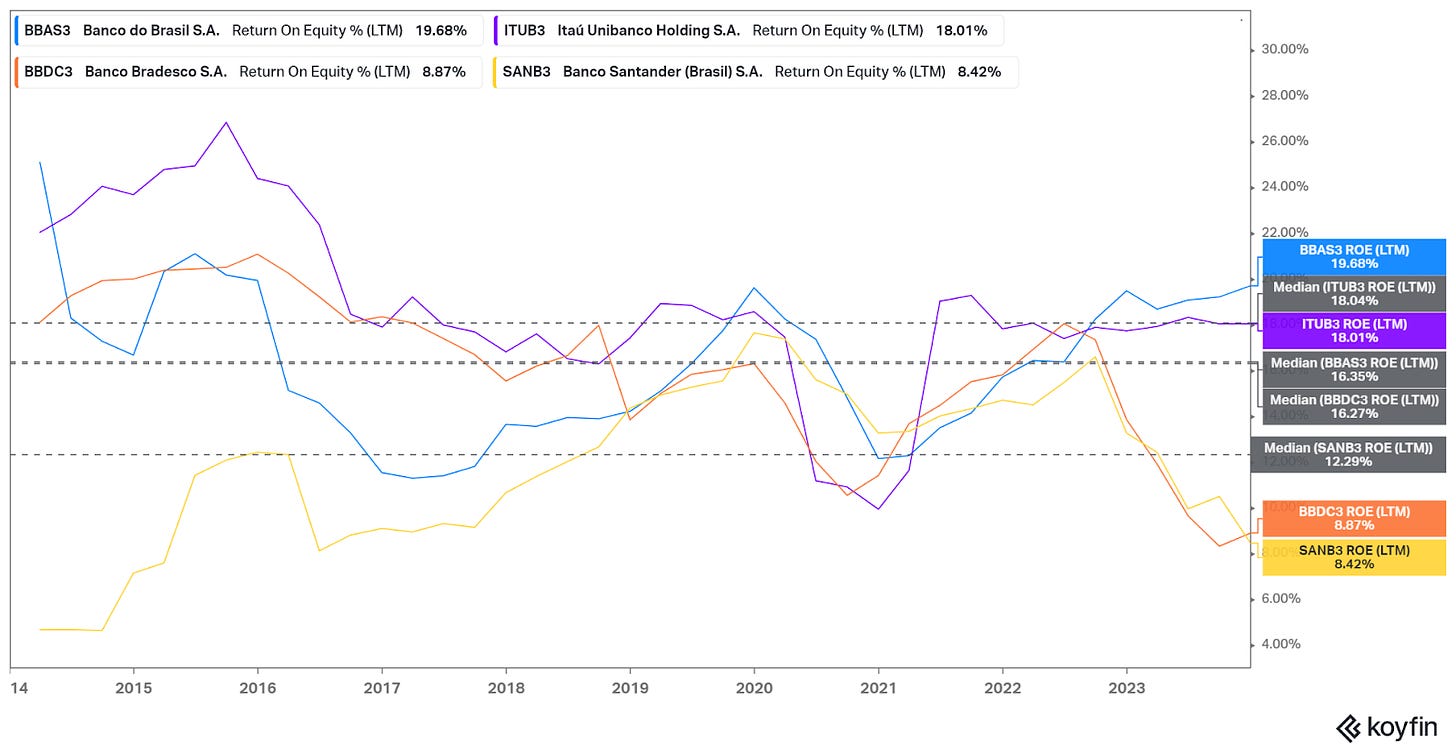

When we look at the big banks (Caixa does not trade publicly) we observe that their average profitability is even higher. Although profitability clearly trended down after 2010 and 2014, the levels rarely crossed below 15% ROE.

Later, we will see that the main drivers of this profitability are high credit spreads and high service revenues. These are the results of low competition. Then, we will analyze if the trend is changing now, thanks to higher competition from digital banks.

1.3 Heavy Weight of the State in the Credit Markets.

The Brazilian State is a big player in the credit markets across many dimensions.

As mentioned above, two of the major banks (Banco do Brasil and Caixa) are government-owned (BdoB only 50%). In total, public banks control 40% of system-level assets.

On top of that, the government intervenes on the interest rate of about 42% of all credit (something called credito direcionado or directed credit, in contrast with credito livre or free credit). The markets of rural credit, mortgages, and infrastructure are totally dominated by credito direcionado, with rates close to or below 10%.

The banks are not always compensated for the credito direcionado. In some cases they can receive cheaper funding (say BNDES), and in others they receive compensation from the Central Bank (for example on 50% of directed rural credit). However, banks generally make less money from these asset. The difference is made up in the free market, where rates are above 20% for companies and 30% for individuals.

Finally, the State absorbs almost half (45%) of all banking assets in the form of public debt. This does not show up in the banks’ credit book but rather in the securities book (the banks call this TVM or Titulos Valores Mobiliarios, tradeable securities). This asset class occupies half of each banks’ balance sheet. This market is not intervened, and therefore rates are higher than the monetary rate, but private credit is crowded out.

1.4 Historically Positive Real Interest Rates

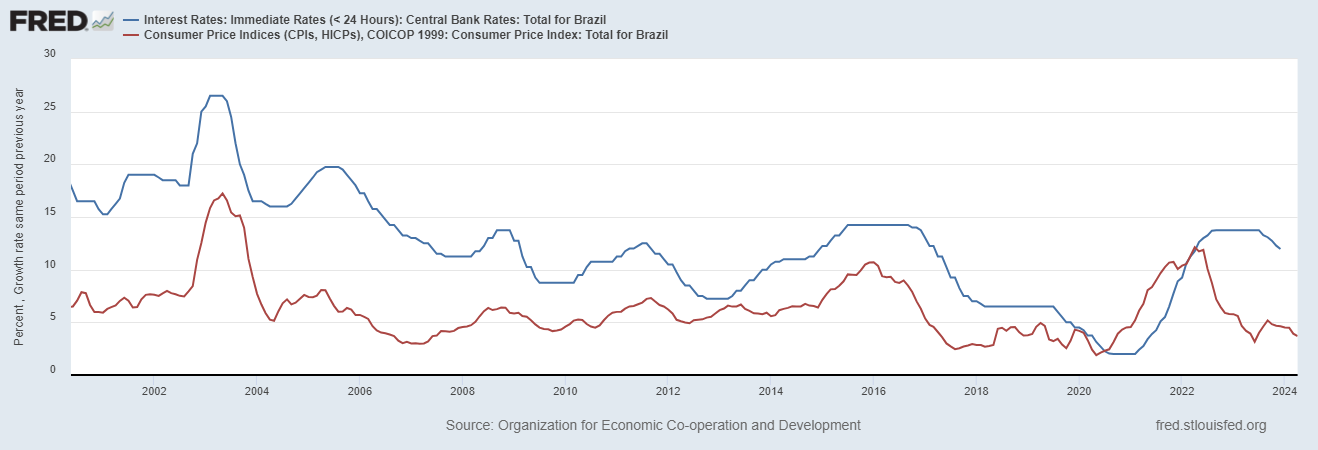

As was mentioned in my Brazilian Stocks Primer, Brazil has consistently shown positive real interest rates. Even during the 2014-2016 recession, the Central Bank decided to raise rates against surging inflation. I believe the reason behind this policy is Brazil’s memory of high inflation rates during the 1980s and 1990s. As we can see below, this policy was only abandoned during COVID-19, and the BACEN was quick to raise rates when inflation appeared.

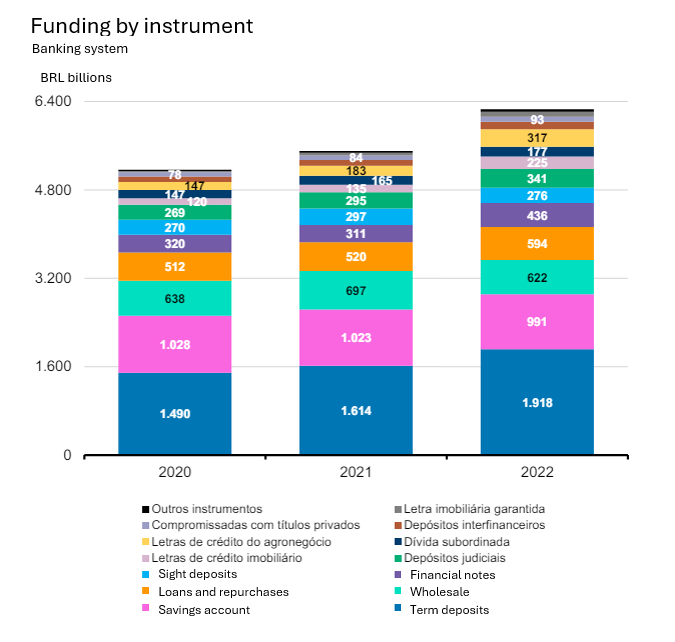

Positive (and high) real policy rates are a detractor to bank performance. The reason is that they elevate the cost of funding. First, they do so by setting a higher benchmark for banks to match if they want to keep deposits and generally elevating the cost of credit in wholesale and debt channels. Second, by providing an attractive rate of return, they incentivize people to save in interest-generating vehicles. The chart below from BACEN shows system-level funding sources (with my translation for the biggest categories). Sight deposits are only a small portion of funding, with most coming from remunerated accounts (term and savings) and different forms of wholesale and debt.

1.5 Effects of the Monetary Rate on Profitability

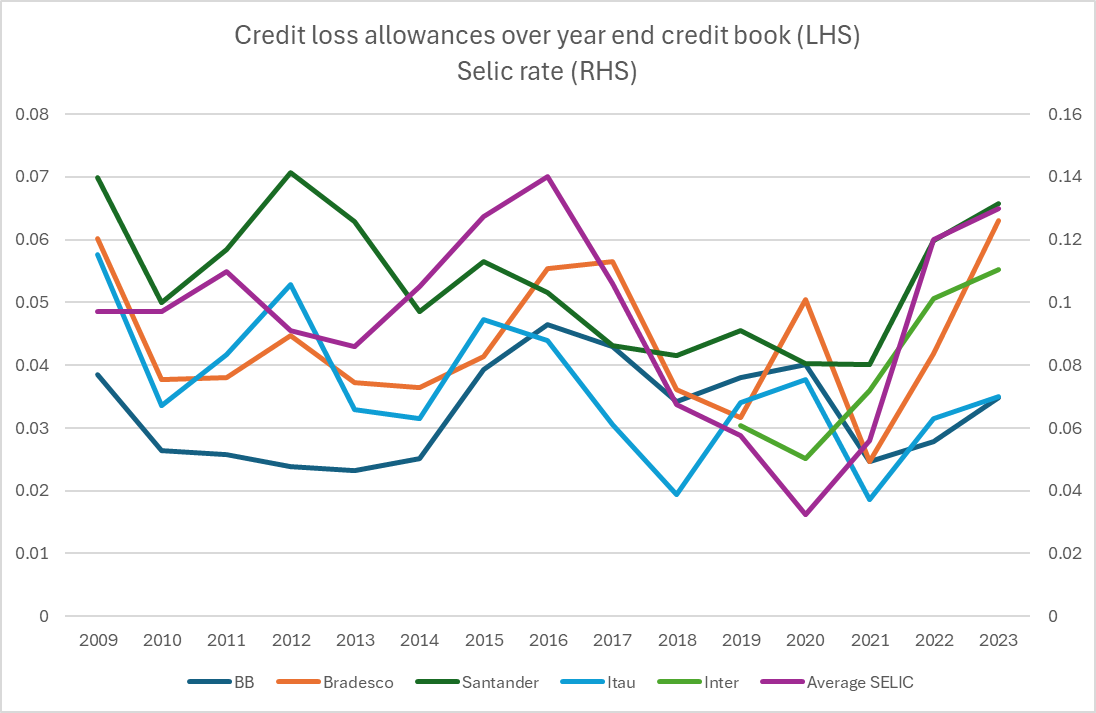

The BACEN monetary rate obviously affects the banks’ ROE. The chart below shows an intuitive correlation between the main banks’ ROE and the policy rate in green on an adjusted scale. I believe the policy rate (SELIC) affects profitability via three mechanisms: cost of funding, holding return on securities, and level of delinquencies.

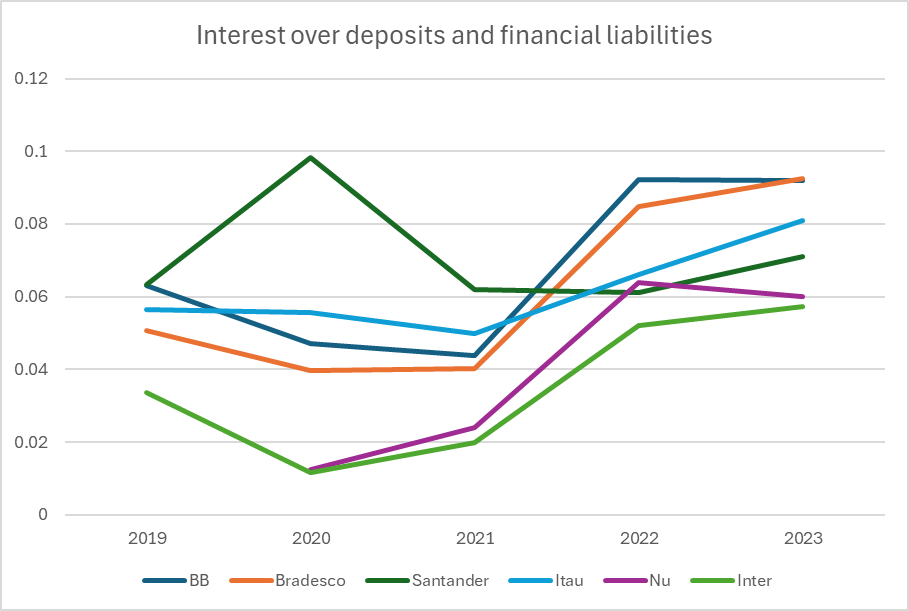

The cost of funding has been discussed above. Brazilian banks' funding is sensitive to policy rates and, therefore, will generally offset a large portion of the improvement on the asset side from higher rates.

On the asset side, generally, about 50% of the banks’ assets are in debt securities, the enormous majority of which are government securities. These securities generate an offsetting effect to changes in policy rates. When rates go down (up), the securities increase (decrease) in fair value, therefore temporarily increasing (decreasing) ROE. In the long term, though, the spread of these securities is low in any regime, as they are competitively priced.

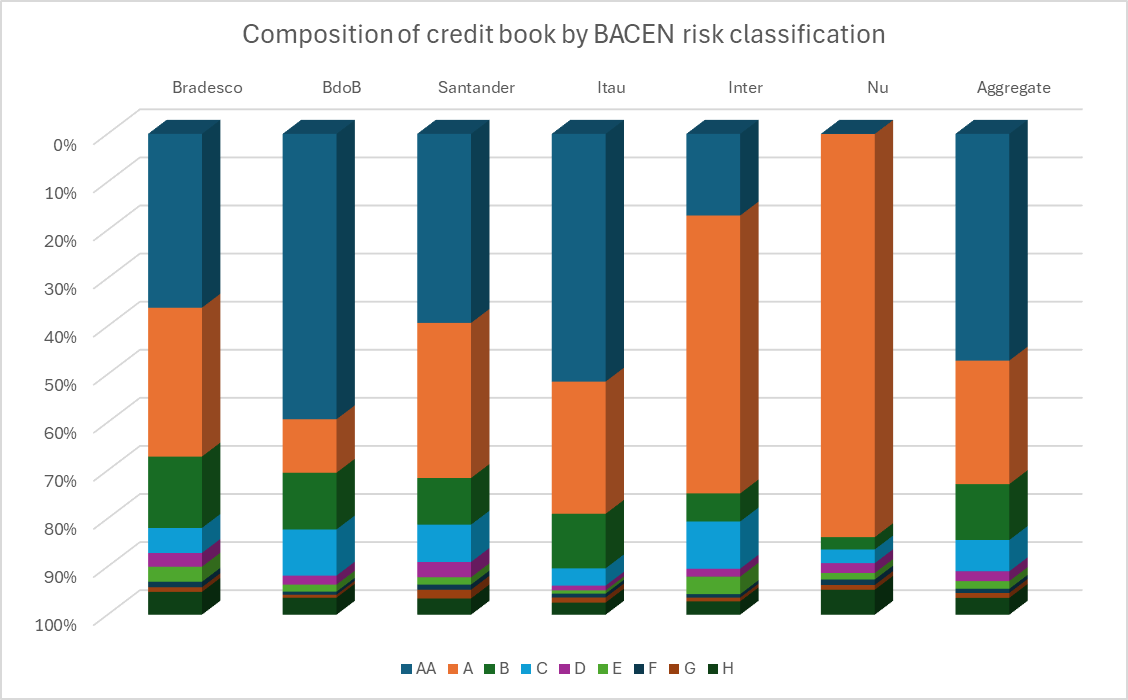

Finally, strong upward movements in the rate clearly increase delinquencies. The reasons are obvious: higher cost of credit for individuals, a colder economy, and a lower appetite from banks to roll over debts. However, I do not think the level of rates affects delinquencies if rates are relatively stable. Rather, rate volatility can cause mayhem. Once rates are stable at a higher level, delinquencies should decrease as banks adjust their credit policies to the new scenario. This will be important when analyzing banks with currently high provisions and relatively worse credit-rating clients, like Bradesco, Santander, Inter, and Nu.

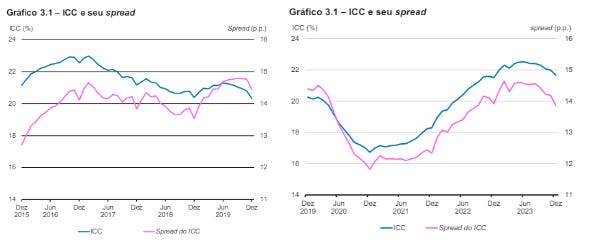

Finally, a big driver of bank profitability, credit spreads over free credit, is not affected much by policy rates. The charts below from BACEN show the median cost of free credit (ICC, blue, LHS), and the median credit spread (pink, RHS), from 2015 to 2019 (left-hand chart) and from 2019 to 2023 (right-hand chart). When comparing with the monetary policy rate from the previous section, we find that the policy rate modifies the cost of credit and the spreads, but not too much. For example, from 2016 to 2020, the SELIC rate went from 14.5% to 2%, but the cost of credit only decreased by 6/7 percentage points, and the credit spreads were basically flat until 2019, after which they decreased by only 2 percentage points.

1.6 Credit Income Sources and Market Share

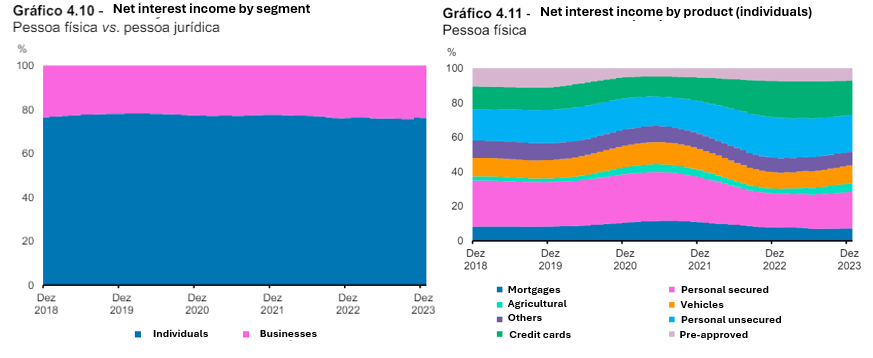

The charts below show the sources of credit income (system-wide, after provisions, translation by author from BACEN). Individuals are the main drivers of profitability, with the main products being personal loans and credit cards.

This is caused by the importance of directed credit at subsidized or limited rates. Directed credit makes up 40% of business credit, particularly in infrastructure (100%) and agricultural activities (100%). In the case of credit to individuals, directed credit also occupies 100% of rural and mortgage credit.

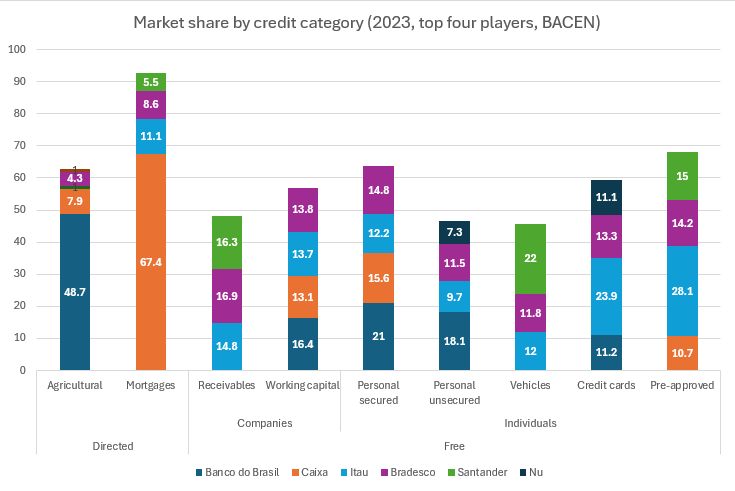

When looking at the market shares, we refer to the comments from Section 1.1. Banco do Brasil and Caixa dominate in the directed areas. Further, the incumbent banks are strong in individuals, but Nu is already making inroads in two important income-generating areas (credit cards and unsecured personal loans). The incumbents also dominate free credit to businesses.

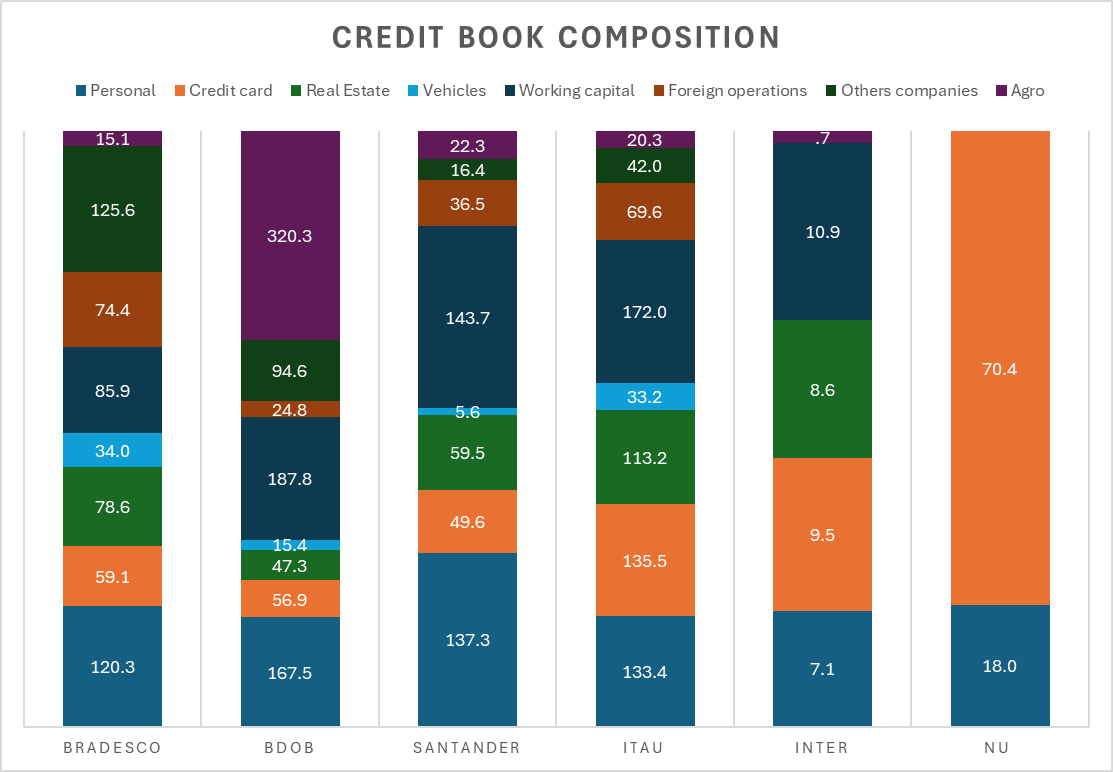

Finally, we can observe the largest exposures below. In particular, I would call attention to the exposure to credit cards and personal loans for Bradesco, Santander, and Itaú and the relatively lower exposure of Banco do Brasil. Also, on how Inter is playing a more diversified strategy than Nu, despite its smaller size.

1.7 Importance of Service Revenue

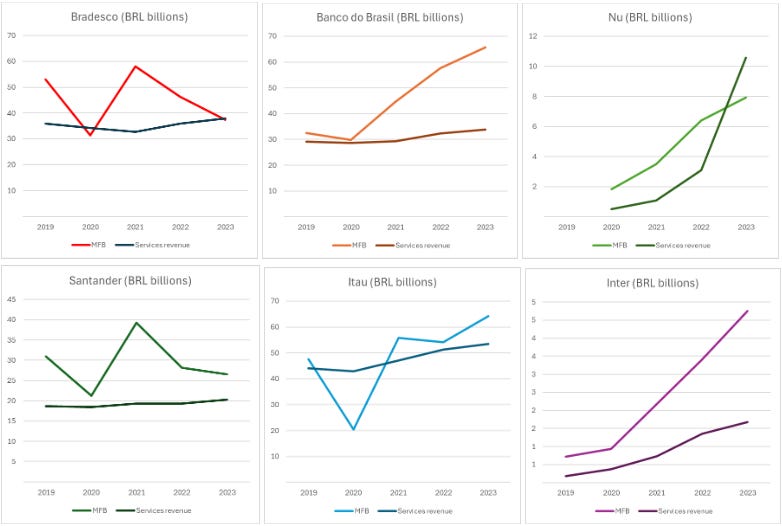

Service revenue is an important driver of bank profits. As seen in the charts below, service revenue is comparable to net interest income after provisions (MFB in Portuguese) for most banks. Of course, this is not comparing apples to apples, given that MFB is a profit measure, but it still gives an idea of the importance of services. Further, service revenue is more stable than credit income.

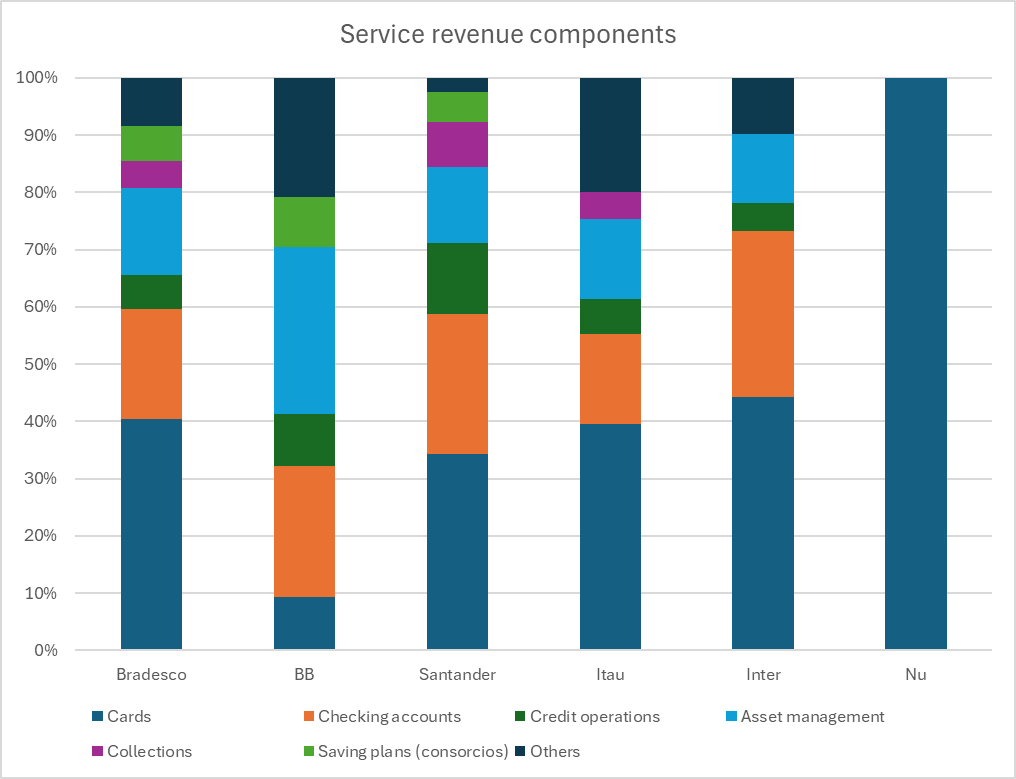

As shown below, most service revenues are generated from individual products, like credit cards and checking accounts. This is one of the drivers behind the challenge from digital banks to the incumbents, as they compete specifically in this category. Insurance operations (important for Bradesco especially) have not been included for comparability.

1.8 Beware of the Exchange Rate

In the medium term, the Brazilian economy is relatively decoupled from the exchange rate compared to what one would expect from an emerging market. As I covered in my primer on Brazil, the country is relatively closed, so many products are not traded, and therefore, their prices are determined internally.

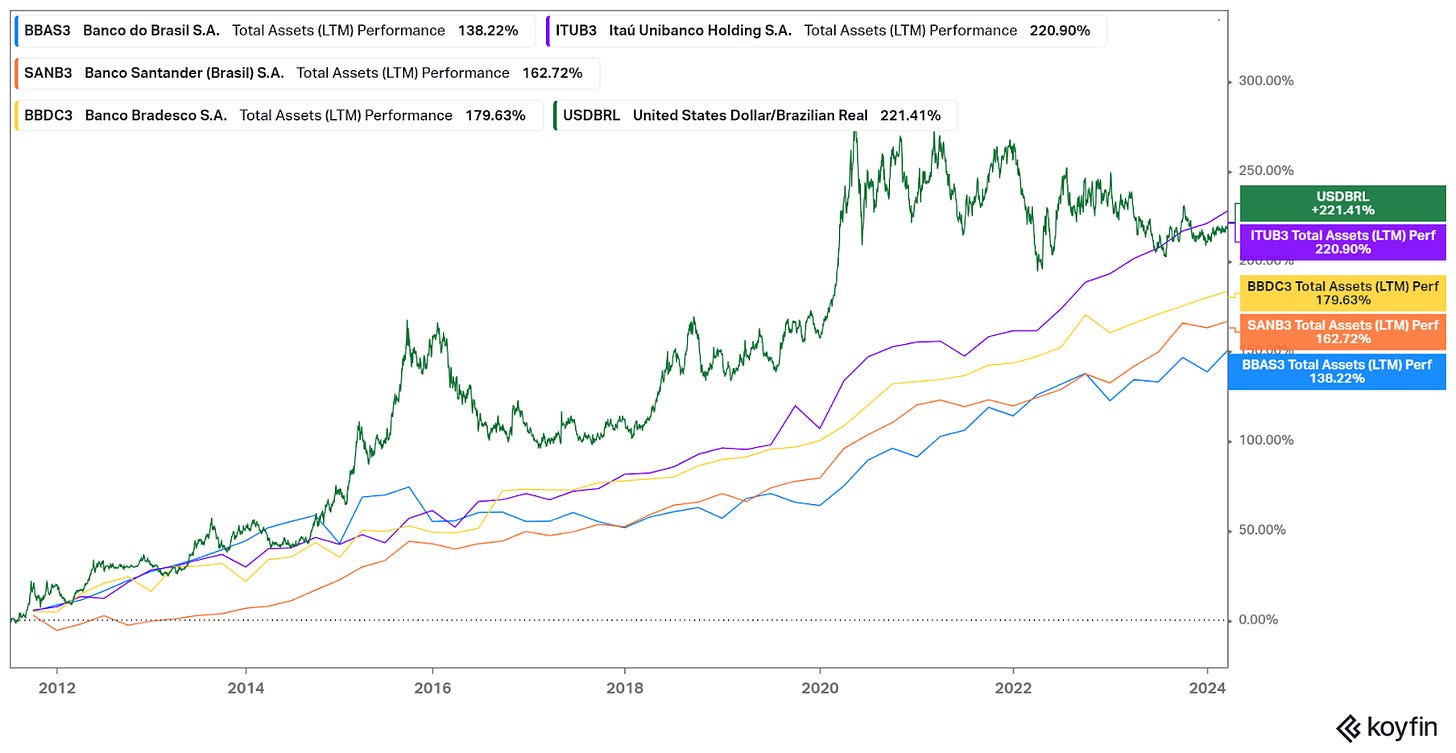

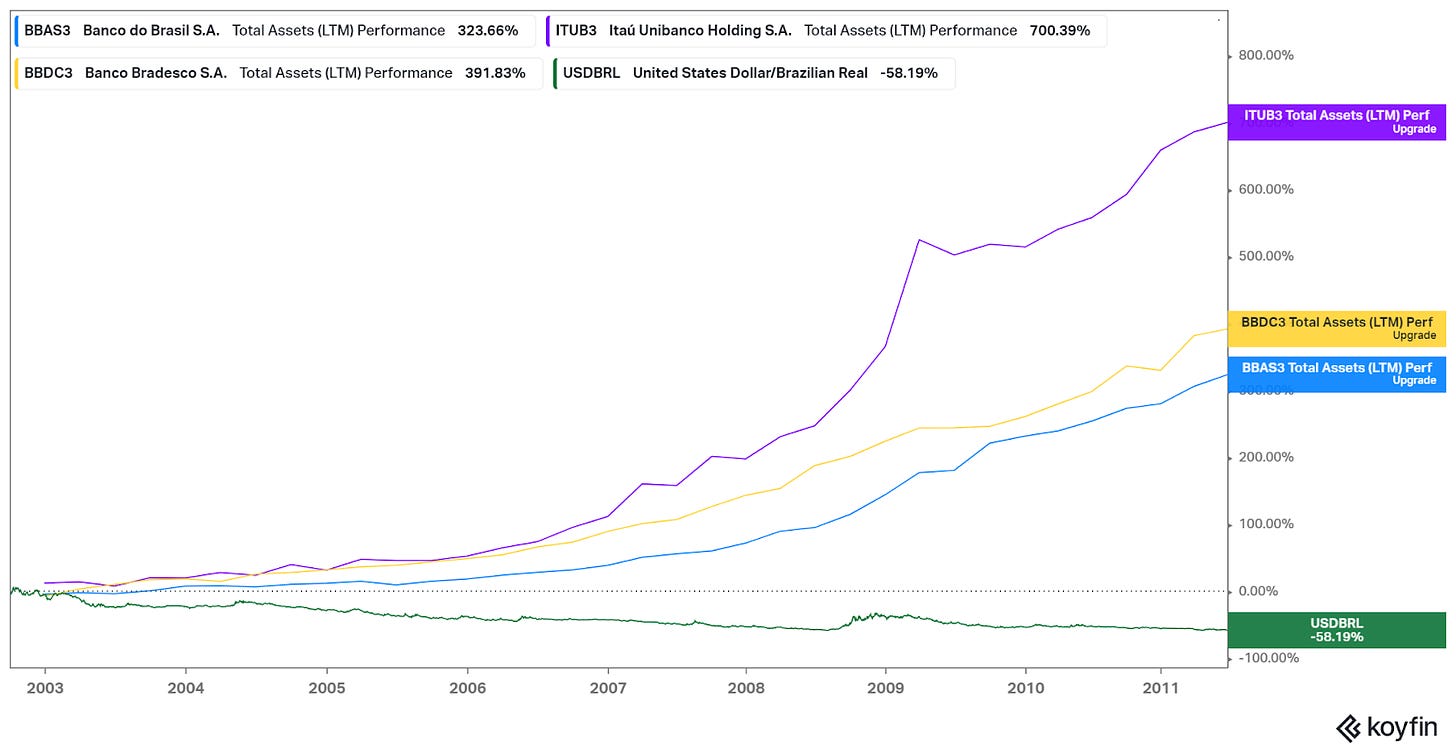

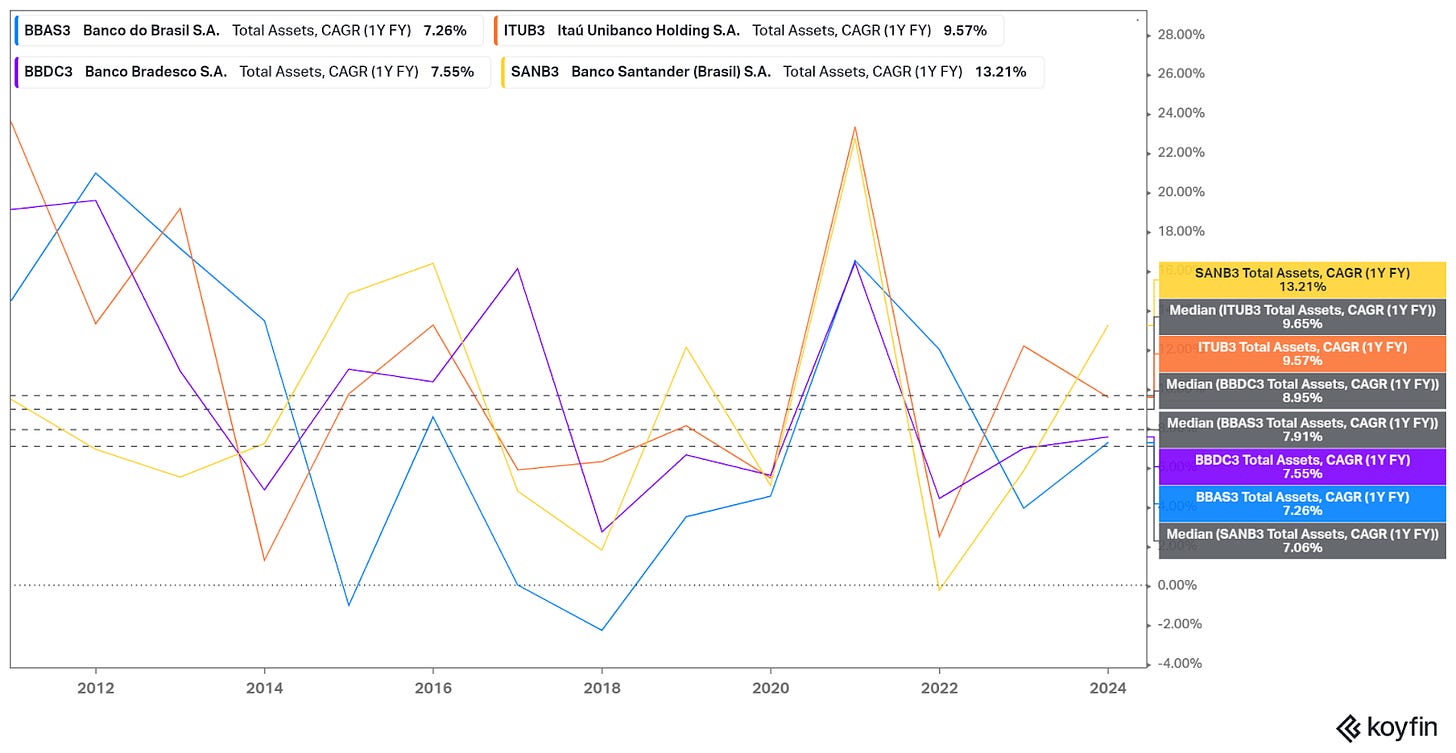

This has important connotations for foreign investors in Brazilian banks. For a bank with a determined level of equity and a cycle-average return on equity, a depreciation (appreciation) of the currency will drastically decrease (increase) the dollar value and return of that equity. This is evident from the chart below, which compares the asset growth of the main banks (in BRL) with the US dollar to the growth of the Brazilian real exchange rate between 2011 and today. Bank assets do not offset the movement of the exchange rate.

The chart above shows a period of strong depreciation, but the opposite is also true for a period of strong appreciation. For example between 2002 and 2011, the Brazilian real appreciated more than 100% (the rate decreased by 60%), and yet the banks grew assets between 300% and 800% during this period (Santander has been removed for comparison purposes as it was very small at the beginning of the period).

2. Digital Banks versus Incumbents

So far the analysis has been backward-looking. However, for many analysts, the Brazilian banking system is undergoing a significant transformation thanks to digitalization. If digital banks transform the industry, the returns of the past might not reoccur. This section will analyze the bull and bear points for digital and incumbents.

Summarily, the bull thesis on digital banks is based on lower cost to serve and better products, fueling a flywheel of cheap deposit acquisition and market share gains in retail products. This thesis has been true so far and is challenging most incumbents, particularly Santander and Bradesco. However, I believe the payments and credit cards market will become saturated and that having a nice app will not be a sustainable advantage. The commoditization of payments and cards will damage all banks, incumbents, and digitals, with the latter suffering more. The competition will migrate to the issue of principality and sound credit practices, an area where digital banks do not have an advantage.

2.1 The Bull Thesis on the Digital Banks

The Brazilian situation fits the digital transformation narrative perfectly: an oligopolistic, heavily regulated market that underserves customers is transformed via digital products that offer better service at a lower price; the digital champions quickly grow and make profits, mostly taken from the incumbents and a portion of the surplus is returned to customers.

The bull case for digital banks is based on the cost of service and economies of scale and proceeds in stages:

Originally, digital banks offered consumers a similar or better service at a lower cost than traditional banks. The focus is on small underserved customers, like unbanked individuals, young people, and small business owners that cannot accept credit card payments. The first products under attack were payments and credit cards, for example by offering small businesses cheap payment terminals, or QR payments to young people without credit cards.

This dynamic attracts cheap deposits, allowing the banks to grow.

Because most services are digital and automated, the digital banks’ cost structure leverages with size, increasing the banks’ margins (or conversely decreasing the efficiency ratio).

Finally, because digital banks have a smaller cost structure, they can offer customers a lower risk-adjusted cost of credit, gaining market share in the credit market.

The flywheel continues as digital banks add more complex services like asset management, insurance, and mutuals and move into more affluent or complex customer segments (like companies).

The first stages of gaining market share in individuals, growing the balance sheet cheaply, and leveraging the cost structure, are becoming true. There are many signs of this.

First, digital banks are still small compared to their peers but are growing fast. For example, the largest digital bank, Nu Holdings, has about BRL 240 billion in assets compared to the incumbents, which manage between BRL 2 and 3 trillion each. However, it has grown its assets by 400% since December 2020.

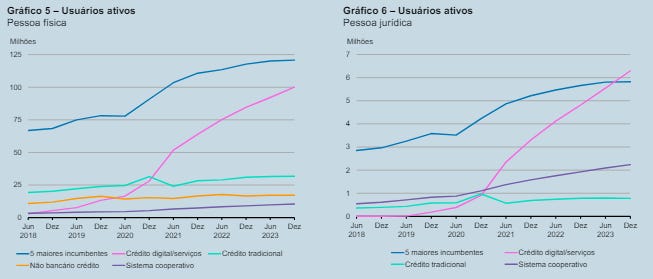

Second, digital banks are quickly gaining customers. The charts below, from BACEN, show active users between individuals (left chart) and legal persons (right chart). The blue line represents the Big 5 Banks, and the pink line all the digital institutions (including payment processors). Mind that a single person might be an active customer in many banks.

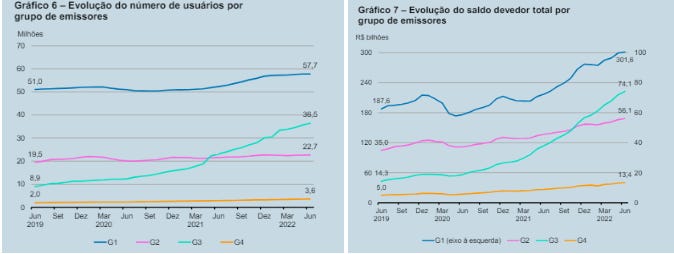

A similar dynamic occurs in credit cards. The left chart below shows the total number of active credit card users up to 1H22, with digital players (in aquamarine) representing a third of all credit cards. The picture is slightly different on credit (right chart), where the large banks (blue) still represent 4 times the size of the digital players (mind that the big banks are on a different scale on the left).

The establishment of a free centralized digital payments system, PIX, has been a big driver of customer growth for both incumbent and digital banks. After PIX was fully launched in 2021, the system added close to 100 million new payment processing accounts (evenly divided between incumbents and digitals).

Third, digital banks have a lower funding cost than incumbents. As seen below, this difference is shrinking but is still very relevant.

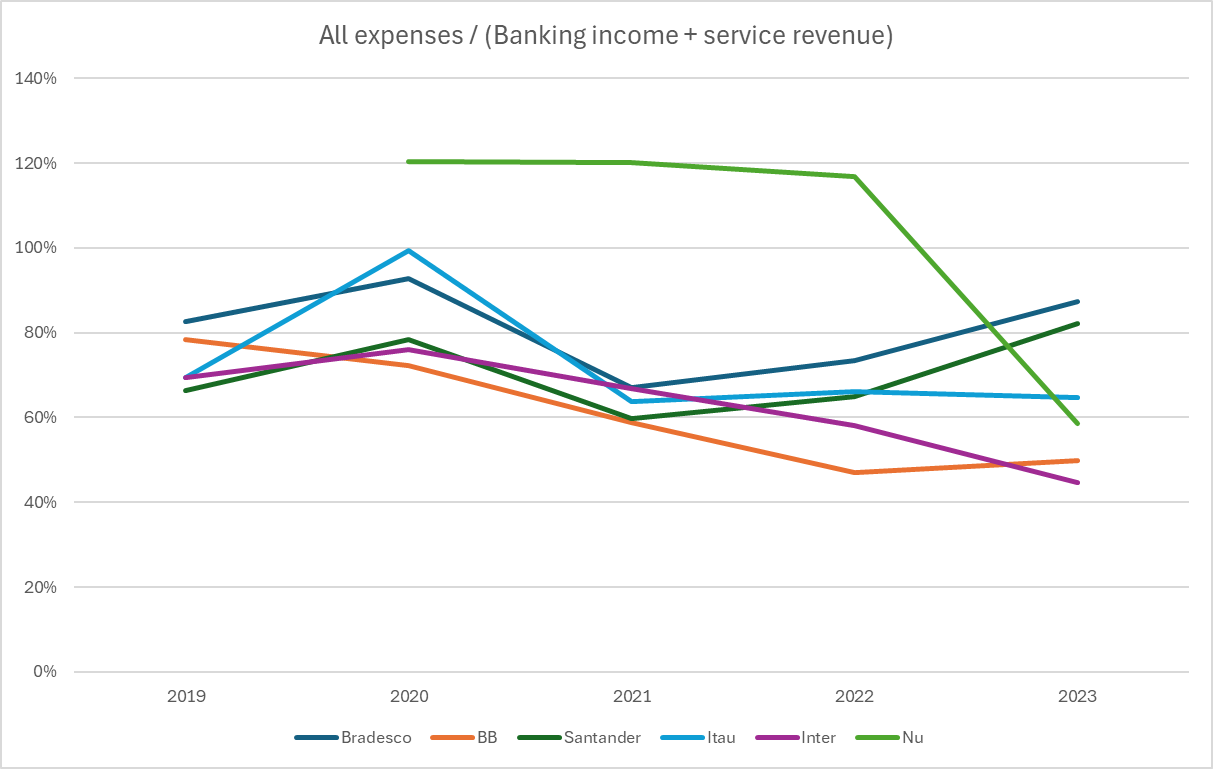

Finally, the digital banks are leveraging their cost structure. Below are the main four banks and the two large digital banks' all-in efficiency ratio (all expenses except income taxes, over net interest income after allowances plus service revenues). We can see how Inter and Nu show a clear and fast improvement in their cost structure and are now sitting below the cost of most large banks. Further, both digital banks are profitable already. Finally, their management teams claim that a big portion of their expenses are in ‘growth or moonshot’ areas that are not paying for themselves yet, so the main services' cost is lower.

2.2 The Bear Thesis on the Incumbent Banks

The consensus thesis on incumbent banks is the opposite. They will have a harder time competing for cheap deposits and will lose market share, particularly in the lower segments of individuals and small businesses. The incumbents will also lose much of the important service revenues coming from accounts, payments, and credit cards as these services become commoditized. Because they have larger fixed structures, operating leverage will work negatively for these banks, potentially putting their viability at stake.

This thesis especially attacks two banks, Santander and Bradesco. There are two reasons for this: one is structural (and valid in my opinion), and the other is circumstantial (and invalid).

First, these two banks are more exposed to lower-income individuals and small businesses than Banco do Brasil or Itaú. This is evident when we look at their credit ratings, service revenue, and credit book composition from Section 1. Santander and Bradesco are more exposed to individuals than Banco do Brasil and to worse credit profiles than Itaú. These are structural disadvantages for these banks, that are not easily solvable. That is why both are trying to launch premium products for individuals in a bid to move upmarket.

The second reason is that because these banks were more exposed to worse credit and were aggressive in lending during the low-rate environment, they suffered significantly as policy rates increased in 2022/23. Higher delinquencies decrease net income from past credit operations and lead banks to curtail credit operations in the future. Both decrease the efficiency ratio's denominator. This generates a lollapalooza effect, whereas these two banks look super inefficient when they might not be (as inefficient) in a more stabilized environment.

2.3 Commoditization and Digitalization

I think simple services like sight accounts, credit cards, and payment processing will potentially become commoditized. More generally servicing low-complexity retail and small business clients will be commoditized. This will affect both the incumbent and the digital banks, but I would argue that it will affect the latter more than the former, given their relative exposures.

Competition is increasing in this segment from two sources.

First, the non-banking payment processors, numbering more than 70 according to BACEN, can only compete in payment and simple account products, as they can neither offer credit products nor pay for deposits. With more incentives to gain customers in this segment, they will drive commoditization.

Second, the incumbent banks have already invested important sums in digitalizing their customer experience and will continue to do so. A useful mobile app with simple account creation and operation will no longer be a competitive advantage. Retail customers with simple needs will have many similar options to choose from, and competition in this segment will move to fees, credit appetite, and advertising or rewards.

One important competitive question is what will happen with service prices as banks increasingly compete for the same clients (and not for previously unbanked clients). Digital banks have an incentive to decrease service costs and grow share, but this strategy risks destroying their own profitability.

2.4 Principality and Competition

Up to this point, it would seem that the incumbent banks are toast. Their main driver of profitability, both in terms of NII and service revenue is getting squarely attacked by the digital banks. The era of high ROE is over.

I would disagree though. I believe the incumbent banks are protected by strong incentives to maintain principality (i.e., being the main bank of a customer). This allows them to maintain the most profitable segments of retail customers, while controlling the digital banks in the lowest-complexity (and therefore lower profit) segments of retail customers. Principality is defended by a series of competitive advantages that are not easily attained by digital banks: access to subsidized and complex credit, access to funding, trust, and breadth of services. We will study these one by one.

Starting with credit, as seen in Section 1.6, the incumbent banks dominate in directed credit and in the more complex free credit areas of businesses and vehicles. They also offer much larger credit card limits than digital banks. Access to credit is a great consideration for customers to maintain their main accounts with a bank. Itaú might not have the best account rates, but they offer me mortgage credit at the expense of maintaining most of my balance with them. In this respect, the digital banks are behind in three areas: they don’t participate in directed credit as much, they don’t have experience in business credit, and they don’t have enough funding to pursue large diversified complex credit operations.

A related aspect is funding. Although businesses do not make a large portion of NII, they make almost 40% of total deposits. This means whoever is financing these businesses will own their banking and own their deposits. The same applies to credit to individuals, as the example from Itaú above explains. Because the incumbents provide credit, they also have better access to deposits, which in turn finance credit.

The next aspect is trust. One thing is to have all my money in a digital bank if I’m a small retailer or young employee with less than a few thousand reals in savings. Another thing is to have life savings in the dozens of thousands or the company’s treasury in a bank. The latter requires a level of trust that may not be easy for a digital bank with no physical locations. It also requires more personalized customer service that does not scale as well as an app.

Finally, we got services. These might be easier for digital banks to attack, with the difference that the incumbents have already been warned and are digitalizing in advance. For example, in order to serve more affluent clients, a credit card is not enough; the bank also needs insurance, more complex loans, and asset management. For companies, services are even more complex, including payroll, taxes, treasury management, permissions, notary, FX, etc. Some of these might not be as easy to digitalize or might not scale well.

These form a self-reinforcing mechanism. The most valuable customers driving credit card and personal loan and account income stay with the banks that offer the widest services and credit opportunities. This in turn provides the bank with more funding and scale to support even more credit. These services, or the customer service and brand investments required to gain trust and principality, do not necessarily scale as well as an app.

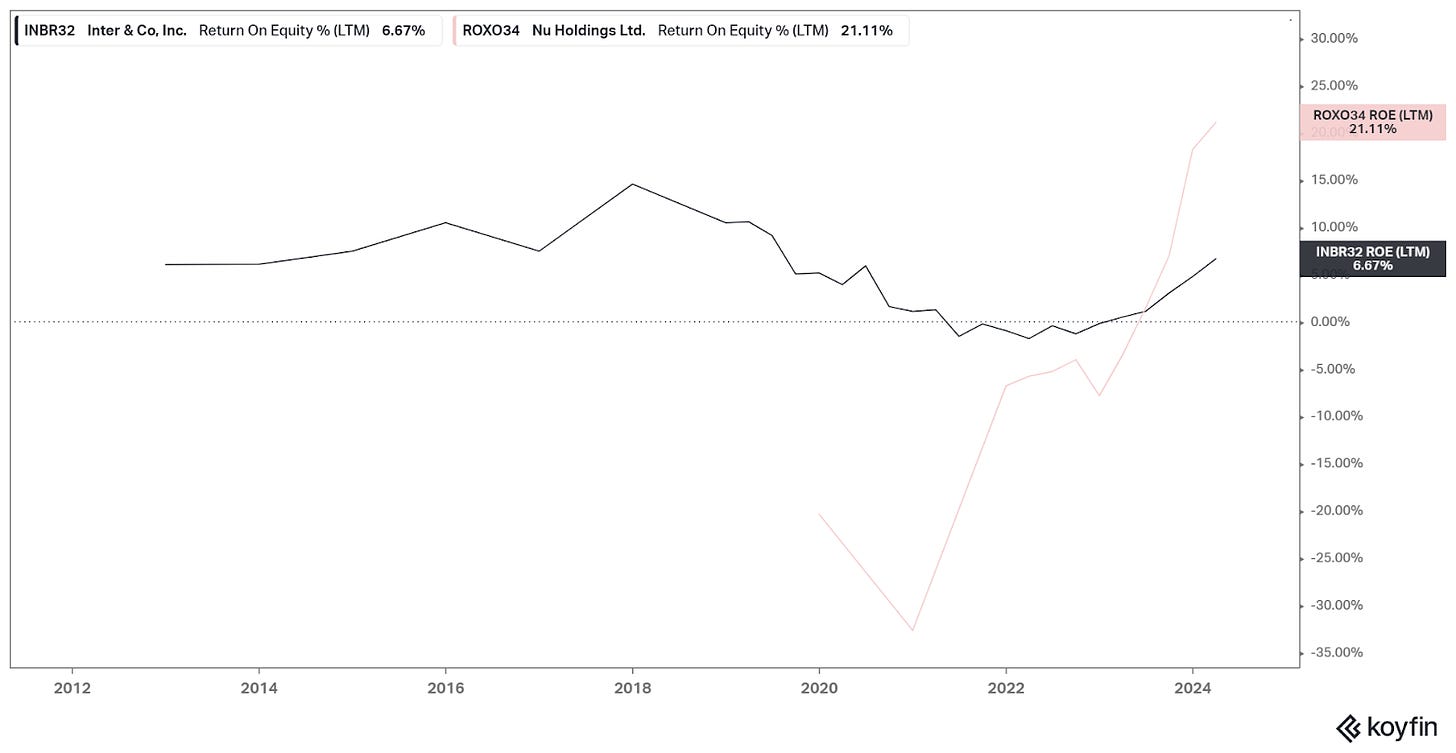

This is, in my opinion, the main challenge for digital banks. We have seen in Section 1.6 that Nu is already making inroads in credit card and unsecured personal loans. However, as Section 1.5 shows, Nu also has the worst credit ratings among the banks analyzed. Its provisions as a percentage of assets are above 15%, three times higher than the average of the other banks. This indicates that Nu concentrates on the lowest portion of the chain. It has not yet demonstrated that it can grow above it.

3. Prices and Opportunities

Based on the above considerations, let us evaluate if the Brazilian banks present opportunities. Let us consider a simple model of book growth, ROE, and P/B multiple, plus movements in the BRLUSD rate. Based on this, you can determine if the banks present an adequate return. Of course, the final decision is very dependent on risk tolerance and a particular strategy, so some readers might disagree with my method.

3.1 Book and Asset Growth

Large banks

Despite Brazil's changing economic regimes, asset growth has been very significant for all the big banks. The comments below reflect BRL figures, as we will deal with the exchange rate separately.

Between 2002 and 2011, Brazil’s economy was booming, commodities were in a secular bull market, and the BRL appreciated significantly. The large banks benefited and grew at mean rates of 20%, with Itaú standing out at close to 28% on average.

Between 2011 and 2024, we can talk about a lost decade in Brazil. Today, the economy is 30% smaller in current GDP and basically flat in PPP inflation-adjusted GDP. The currency depreciated close to 300%, and commodities were very depressed (until the 2022 revival). The slowdown clearly affected the banks, but not as much as one would think. Their mean annual growth rates were still very high, between 7% and 9% (except for the younger Santander growing faster). The figures do not change meaningfully if we shorten the period to 2014-2024 to avoid the last years of the bull market.

Digital banks

Their potential is obviously significantly higher than that of large banks, although it is not infinite. For example, today the large banks have credit books for individuals ranging between BRL 300 and 400 billion. This includes more complex operations like real estate (about 20% of the combined book). Nu already has about BRL 100 billion in credit to individuals. Growing at 30% rates, Nu would reach parity with the large banks in five years, after which competition would become much more fierce.

In this respect, the two banks are taking different routes. Nu is clearly focusing on expanding to other Latin American countries, like Mexico and Colombia, to repeat its success with individuals in Brazil. On the other hand, Inter is trying to grow into more complex segments in Brazil. I believe Nu’s strategy makes a lot more sense.

Finally, I think the issue of digital bank growth is better evaluated by inversion. Instead of considering the return coming from growth, let us consider what type of growth is embedded in a certain P/B multiple to derive a specific return.

3.2 Returns on Equity

Large banks

Using the same approach as above, we can observe how returns for the large banks varied between the expansion period (2002-2014) and the recessionary period (2014-2024). The returns are impressive for the large banks in both periods, with Santander lagging behind.

Now, the question is what could happen in the future. This question has four main components: funding, credit income, service revenues, securities income, and delinquencies. These issues were treated in Section 1.5 and Section 2.4.

My thesis treats funding, credit income, and service revenues as a bundle. The most profitable clients do not decide where to bank based on which product is cheaper in isolation but based on the whole offer of services and credit. This provides incumbent banks with competitive advantages that are not as easily attackable by the digital banks.

Regarding securities, they make up 50% of the banks’ balance sheets, but they probably do not represent half of interest income. The reason is simply that the government securities market is way more competitive, without barriers to entry, and that funding is also competitive in Brazil. I have no information on the spreads, but I would assume they are low. Given this, the expected decrease in government rates should not meaningfully decrease the banks’ ROE.

Finally, we have delinquencies. My thesis was that delinquencies are not affected by the level of rates but rather by their volatility. I have no way to predict future rate volatility, but we can be sure that the 2021/23 period, which led banks like Bradesco and Santander to post high delinquencies, was pretty abnormal. In a more normalized environment, I think the ROE of these two banks should converge closer to their historical mean and peers.

Therefore, I do not agree that the incumbent banks' future ROE will be lower than during the recessionary period. On the contrary, the recent ROEs represent a challenging period for Brazil's economy and high interest rate volatility. If the future proves less challenging, ROEs should actually improve.

Digital banks

I am a lot less bullish on the long-term ROE of digital banks because of the limits to their market potential. I believe their ceiling is becoming a regular bank, with the potential to underperform over the long term if they become encapsulated in the lower segments.

3.3 Multiples

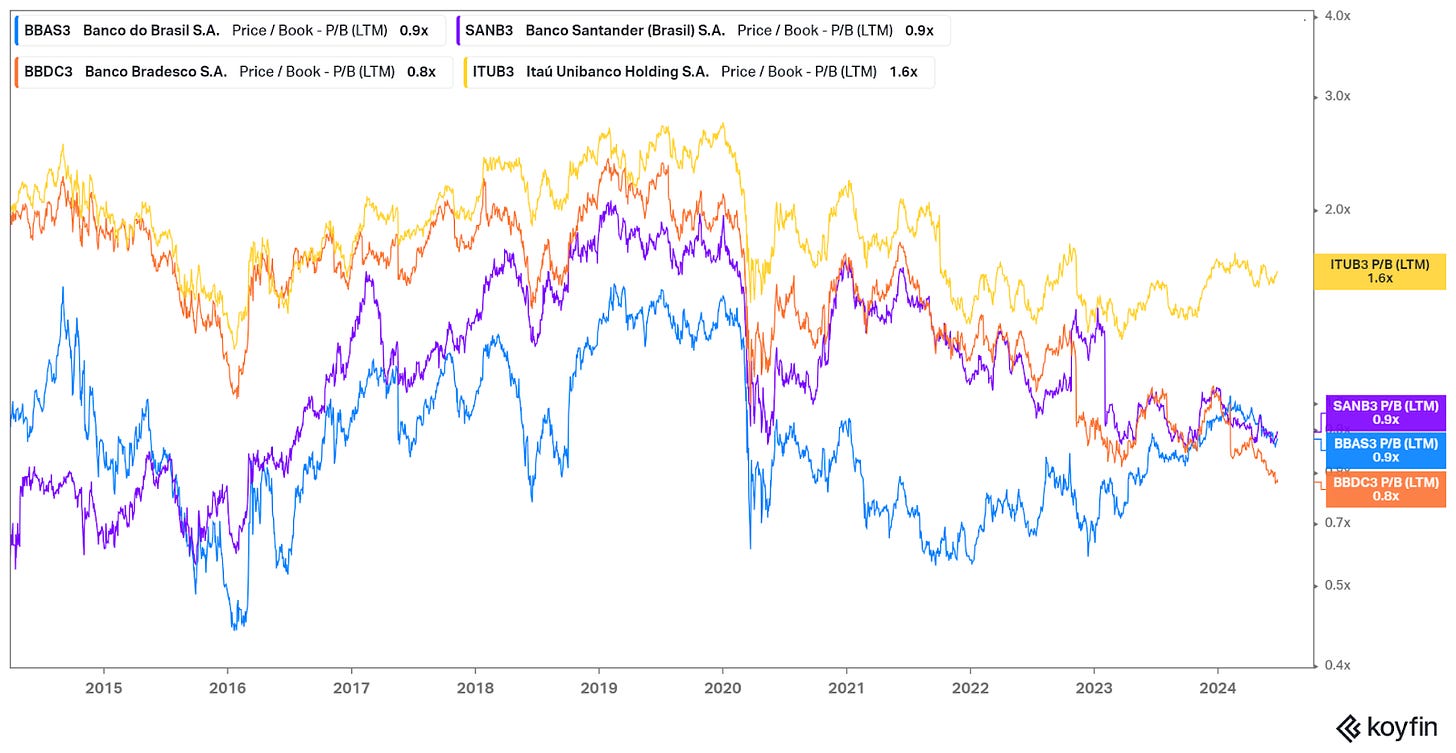

Large banks

The big banks have generally been priced at 1.5/2x P/B multiples, with Banco do Brasil traditionally below, probably because of fear of political influence, and Itaú at the top, justified by its asset growth and ROE overperformance. From a P/B standpoint, we cannot say that banks are expensive today. In fact, if anything, a recovery for Santander and Bradesco could lead to their repricing closer to Itaú in the future, although I would not take that thesis to the bank (no pun intended).

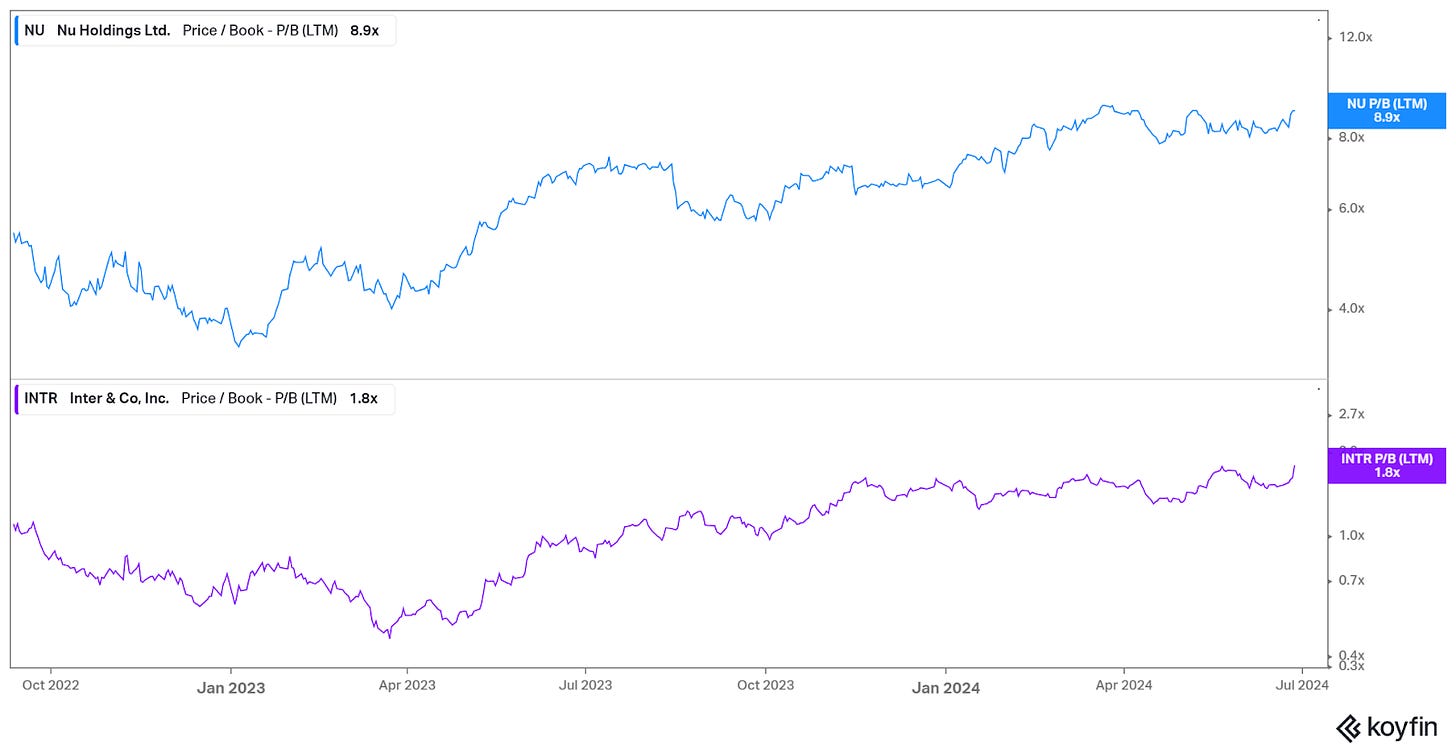

Digital banks

Digital banks are a different story because of their super high multiples (at least in the case of Nu). I believe it makes sense to invert the multiples and ask how much growth is needed to justify a specific return in BRL over the long run.

First, I consider that in the long run, even if these banks totally displace the large banks, their profitability will probably not be higher than that of the oligopolistic large banks. In the end, the whole premise of the model is based on more competition, i.e., lower returns. After they eliminate all the large banks, they cannot grow much faster than them either.

In this super bullish scenario, we are talking of banks producing an ROE of about 15% and growing about 7%. If they traded at a P/B of 1.5x, we would expect a compounded return of ~17% on the investment (in BRL). However, we are considering Nu at a P/B of 9x. If it eventually displaces all other banks, it will trade like a bank, or say 1.5x. This means that Nu needs to grow 6 times from its current size only to offset the effect of its multiple shrinking.

Of course, the above exercise is not super realistic. Nu would become the largest bank for individuals by growing 6x from its current size (basically equivalent to today’s Santander and Bradesco retail operations combined), but it would not displace the other banks, therefore it may not stop growing there. It could also grow to other countries like it is doing now. Most importantly, the multiple might be much higher for a long time, allowing the investor to reap the benefits of growing without paying the price of maturing on the multiple. However, the exercise illustrates that investing in Nu at these prices requires significant optimism in two areas: first that the bank will grow way above peers without reducing its returns on equity; and second that someone else will be willing to pay similar multiples on a larger company.

Inter, on the other hand, seems more interesting from the price perspective, although it is coming late to the same market, and it might have even more difficulties growing and rising margins.

3.4 Conclusions (and the exchange rate)

It is clear from the above that I’m not super bullish on the digital banks at these multiples, even without considering the issue of the currency movements. Therefore, this portion will concentrate only on the large banks.

As we saw, even during an economic downturn, these banks grew at 7% rates and posted 15%+ ROE. They could post interesting returns if they could repeat this feat, even while trading at a P/B of 1x (except for Itaú). Even if the future ROE was slower due to higher competition, and assuming that Brazil continues to stagnate, the returns could easily surpass 15%.

However, the catch is the exchange rate, a huge risk that should be embedded in the return requirement for these banks. Even when growing and posting high ROE, the stocks of these banks are basically flat since 2010 in US dollars (Bradesco is actually down 40%). The culprit has been the 300%+ depreciation of the Brazilian real. As mentioned in Section 1.8, the exchange rate can liquefy the books of these banks, destroying USD-denominated profits.

I am no macro forecaster, so I have no way of predicting what will happen with the BRL in the future. If we approach it neutrally, considering a 50/50 change of an appreciation or a depreciation, then the large banks are very interesting over the long run. On the other hand, if we assume that there is a higher chance of the BRL depreciating, then a premium to the required return on the investment should be added to accommodate this risk. I leave that task to the readers.

Resources

The Brazilian Central Bank (BACEN) does fantastic up-to-date research on the financial system. The two main periodical pieces are:

Report on Banking Economy - BACEN (in Portuguese up to 2023, in English up to 2020).

Financial Stability Report - BACEN (in Portuguese).

IE-UFRJ has an Observatory on the Financial System, with several papers on Brazilian banking and a great Youtube channel:

Porto, Gabriel & Martins, Norberto & Bonatti, Lara & Albuquerque, Francisco & Ferreira, Leonardo. (2024). Mapeando as fintechs no Brasil. (Mapping Brazil Fintechs)

Martins, Sarno, Boechat Filho, Macahyba (2021). Taxa de lucro dos bancos no Brasil: uma análise dos seus componentes e de sua evolução no período 2015-2020 (The profit rate of Brazilian banks: an analysis of its components and evolution in the 2015-2020 period).

Thanks!