Brazil Capital Markets Primer

Stock exchanges, investment banks, insurers and payment processors.

This primer covers the Brazilian capital markets. We will go over the system's structural characteristics, main current trends, and some of its larger public companies. It can be considered an addition to the Brazilian Banks Primer and the Introduction to Brazilian stocks. You don’t need to read those articles first, but I recommend you do so at some point, as they provide more color on the financial system of Latin America’s largest economy.

Brazil holds the largest capital market in Latin America, responsible for as much as 50% of the region’s capital-raising activity. Yet, it is still a dwarf(ed) market, in large part because of a crowding-out effect driven by large state deficits. A big portion of credit goes to the state at high inflation-adjusted rates. The Brazilian political elites are trying to reduce the deficit problem, potentially leading to a large increase in funding to the private sector in the next few years, a trend that can be captured by the companies in the capital markets sector.

Because of the above crowding-out, the cost of capital in Brazil is high. In order to earn their capital, the companies of the capital markets sector have to be great operators, with high margins, high capital efficiency, and intelligent competitive strategies. It is a market of great companies, most of which are growing while paying large dividends, but with almost none of them trading at more than 12x P/E.

It is, I believe, a market full of opportunity with very interesting companies at very interesting valuations.

Index

Overview of the Brazilian capital markets

Players

Asset classes

Competition

The role of the state

Public companies

Monopoly stock and securities exchange: B3 SA

Investment banks and asset managers: BTG Pactual and XP Investments

Insurance: BB Seguridade and Caixa Seguridade

Payment processors: Pagseguro, Stone, and others.

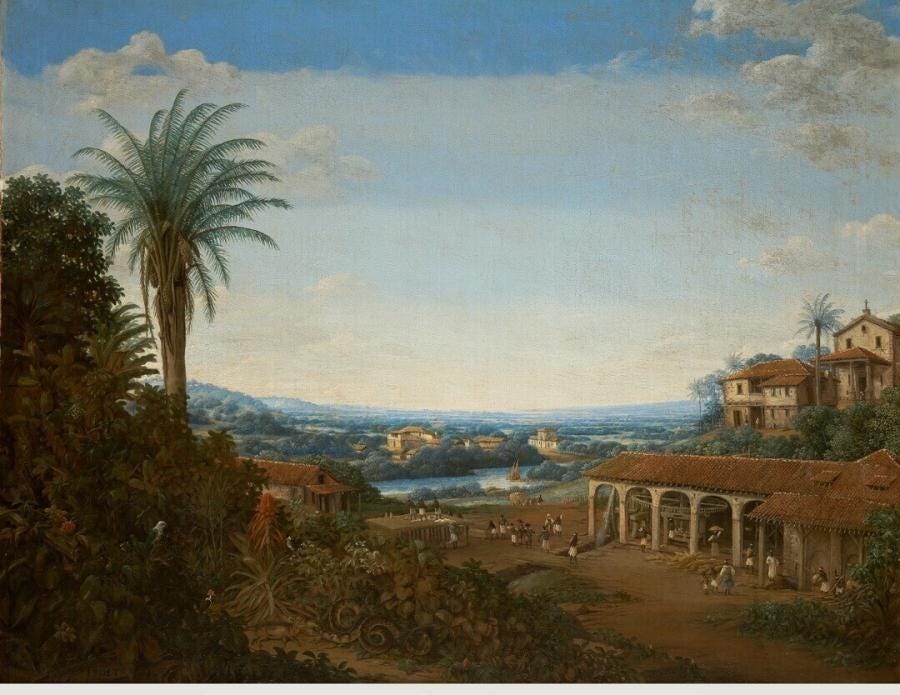

Overview of the Brazilian capital markets

In this section we go over the main structure of the Brazilian capital markets: its players, the size of each asset class, the competitive dynamics between players, and the important role of the state in capital allocation.

It is a market dominated by a group of five banks, that have leading market shares in lending, bond markets, asset management, payments, and insurance. Although these banks have lost market share to a host of specialized players in each arena, they are still strong in each of the areas, and dominant when considering the aggregate market.

The specialized players, after an early stage of strong growth driven by providing a good product to previously underserved customers, are now trying to expand into other verticals. In this way, they are becoming more similar to their large bank brothers. It is yet unclear who will emerge victorious from this competitive battle, or if a good balance will be achieved.

Finally, it is a market that has been crowded out by large government borrowing, and consequent high interest rates. The cost of capital is very high, with safe government bonds yielding very high inflation-adjusted rates and absorbing a big part of all available capital. This has led to a relatively small market to private investment, a situation that could change in a few years. It has also led to fantastic operators.

The players

Mega-banks: The five brothers —Banco do Brasil or BdoB, Caixa Federal, (both state-controlled), Itaú, Bradesco, and Santander Brasil— dominate several segments of the capital markets, particularly credit, insurance, and asset management.

Together, they hold a combined balance sheet of nearly R$11 trillion, with 70%+ market share of of bank deposits, assets, and credit.

They concentrate about 65% of assets under management (AuM) in investment funds.

They also dominate in insurance, where the mega-banks market share ranges from 50% to 80%.

Neo-banks: They are digital banks offering all banking products (deposits, credit cards, payroll loans, mortgages, insurance, investments). The best-known examples are Nu and Inter, which have combined assets of about R$300 billion. Originally they started as mostly payment processors or deposit-only/credit card banks catering to lower-income segments (micro-businesses, gig economy, informal workers), but are now steadily expanding into the upper market.

These two segments are explored in more detail in the Brazilian Banks Primer.

Payment processors: A subcategory of fintech that focuses primarily on card acquisition and basic account services. The difference between payment processors and neo-banks is typically one of asset scale, with neo-banks offering a broader range of services because their balance sheet allows them to. Pure-play leader players in this segment are Pagseguro and Stone, but the dominant market share is still held by large bank subsidiaries (Rede from Itau, Cielo from Bradesco and BdoB, and GetNet from Santander).

Other banks: There are plenty of mid-sized and small banks and processors not covered here.

Investment banks, brokers, and market infra: In Brazil, there is no effective Glass-Steagall-like separation, meaning a single bank can own both investment and commercial subsidiaries. As a result, all of the mega-banks, particularly the privates Itau, Bradesco, and Santander Brasil, have investment banking arms. Large and neo-banks also provide investment management services and products, offering both their own funds or third-party products. As mentioned earlier, the large banks dominate asset management.

Still, it is worth noting more pure-play companies such as BTG Pactual, arguably the most important investment bank in the country; Banco Safra, a close second; and XP Investments, the neo-broker bridging investment management and previously underserved segments of the capital markets. We will also review the business of B3, the only stock exchange in the country.

Insurance subsidiaries: While the mega-banks dominate the insurance sector, they do so through subsidiaries. Two of these —BB Seguridade (BdoB) and Caixa Seguridade (Caixa)— are publicly traded, while Bradesco and Santander operations are not separately traded. These insurance subsidiaries benefit from exclusive access to their parent banks' distribution networks and operate under a partnership model for managing insurance products.

Asset classes

Bonds: The Brazilian bond market is the largest financial asset class, with about R$16 trillion in value. Bonds make up about 40% of most banks' balance sheets, and fixed-rent securities make up at least 50% of the investment fund market.

On the borrower side, the government is dominant, with about 60% of the market. The rest is mostly financial institutions, with non-financials making up only 7% of the market. Non financial companies issue very little in terms of bonds.

Loans: The loan market (excluding the intra-financial sector and the government) is about R$6 trillion. Most of this is lent to individuals (R$4 trillion), with non-financial corporations making up the remainder. Again, we find that companies have little access to credit vis a vis the government, financials, and households.

Traded and private equity: The Brazilian equity market is the largest in Latin America, with a market capitalization of about R$4.5/5.5 trillion, making it about twice as big as Mexico. This is obviously much smaller than bonds and loans but goes directly to companies. Still, the central bank calculates that there is about R$22 trillion in equity claims in the economy, meaning a relatively underdeveloped equity market. The M&A market alone is about the same size as the public market capitalization.

I believe the reason behind this is the high cost of capital and equity in the Brazilian economy, making it an interesting market to hold and accumulate but not sell equity. Also interesting, whereas foreign investors are small in the credit segment (R$3 trillion between bonds and loans) they are more than 50% of the equity markets.

Competition: the big amalgamation and principality

Although each player operates in specific areas of the capital markets (except for the banks, which are more like octopuses), there is a clear trend toward expanding into other sectors, aiming to become the go-to platform for all of a client financial needs. This is referred to as the “fight for principality” ( or principalidade in Portuguese), meaning the quest to control most of a client's assets.

Why is principality important? There are several reasons:

The digital hyper-growth players initially promised to serve a nation of unbanked masses, only to find out a few years later that most of Brazil’s high-value clients (middle and upper classes, businesses) are already heavily banked. To continue growing, they need to compete upmarket.

There is a “chicken-and-egg” problem in banking services: offering complex products (such as mortgage, car loans, or business financing) requires a large balance sheet. However, clients will only trust a bank with their deposits — providing the funding for the balance sheet— if the bank offers the products they need.

Cross-selling products is much easier than acquiring new customers, particularly in a market where most of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked up.

Almost all of the segments outside of the mega-banks show this type of expansion:

Both BTG and XP have expanded their service to credit cards and wholesale and corporate lending.

Payment processors like Pagseguro are trying to grow their balance sheet and offer the simples loan products (credit cards, payroll loans).

Neo-banks are already more diversified in terms of services, but still want to incorporate more complex products like mortgages, or investment management.

The important role of the state

The Brazilian state plays a massive role in the capital markets, directly and indirectly. I use the term state rather than government because this role does not stem from the executive branch but rather from an institutional, decades-long, law-determined arrangement. This important role is seen in two areas: the weight on credit directioning, and the crowding out effect.

Weight in credit: The state directly or indirectly controls a big part of the lending done to individuals and companies:

Two of the five largest players —Banco do Brasil and Caixa Federal— are majority state-owned. BdoB also has private shareholders, whereas Caixa is fully owned by the state.

Brazilian law caps or subsidizes a significant portion of credit to businesses, mortgages, and agriculture, a system known as credito direcionado (directed credit). This makes up 40% of total lending, with public banks (BdoB, Caixa) dominating the sector. There are also interest rate caps for specific groups, such as pensioners.

The public banks (BdoB and Caixa) have a significant competitive advantage because they control a big part of the regulated credit. This gives them a good base of principality (clients that do most of their business with them) and an upper hand in insurance (via credit life and pensions).

The state also used to control a large portion of corporate credit via the BNDES (the National Development Bank). The bank could direct subsidized or unsubsidized credit to large corporations and infrastructure projects and was instrumental in creating most of the large Brazilian conglomerates. Up to 2016, the BNDES was responsible for more capital lending than the whole public market (debt and stocks) combined. This role was reduced after the Bolsonaro government, and now funding from public markets is twice as big as funding from the BNDES.

Taking political views apart (desirability of the state regulation in these issues versus a freer market) the truth is that many of these regulations tend to shrink the size of the private side of the capital markets. If public banks dominate because of subsidized credit, others cannot compete as much. If most of the financing is done via BNDES, then there is less space for equity markets, etc.

Public debt and crowding out: The Brazilian state has a net liability of more than R$6 trillion. This naturally generates a crowding-out effect, as the state makes up 60% of the bonds market. The need to accommodate increasing government debt puts pressure on long-term interest rates and on the Brazilian Central Bank to maintain higher real rates.

The Brazilian Central Bank is considered independent and has generally been very strict in its policy to defend against inflation in the country. It has been moderately successful, especially for a country that has seen its currency depreciate significantly over the past 15 years. However, the cost has been very positive real rates (reaching as high as 7/8% in 2024, for example).

This is not great for the capital markets, as people can enjoy very safe and high returns by putting their savings on government bonds. Interest rates may also play a role in the BRL depreciation because of international parity. The cost of capital to Brazilian companies is high, and therefore capital flows to the government or to unregulated sectors (consumer finance) versus financing companies. On the positive, the existence of a real cost of capital has clearly led to a much better management culture, which is (I believe) evident for anyone analyzing Brazilian public companies (level of reporting detail, analyst inquisitiveness, and capital allocation prudence).

The opportunity of the crowding-in: The Brazilian establishment is cognizant of the problem posed by government deficits and debt. The center-leftist government of Lula da Silva signed a fiscal-spending rule in 2023 that has the goal of generating government primary surpluses by 2026.

If this is achieved, a large portion of capital which is parked in high-yielding government bonds today would need to find a different use. This would open an interesting window for some of the companies in the capital markets sector. For example, higher availability of capital would probably lead to higher IPO activities (good for the stock exchange and the investment banks). More capital would also lead to lower interest on consumer and company financing, promoting larger but safer credit books for the banks. At low rates, having insurance becomes more economical, etc.

Even though today the state is seen as an impediment, the solving (or amelioration) of the deficit problem can be a tailwind going forward.

Public company overviews

In this section, we go over the most important public companies in the sector. The majority are accessible in US markets via direct listing or via ADRs. Some are only accessible in Brazilian markets or private, but were included to make the description more complete.

We will first review the companies directly involved in the capital markets:

B3: the only exchange in the country responsible for all listed securities trading, and most OTC.

BTG Pactual: the country’s most important investment bank.

XP: the most salient digital broker, the Nu Holdings cousin in the capital markets.

Then, we will review the two largest insurers, BB Seguridade and Caixa Seguridade. Finally, we will review the payment processors Pagseguro, Stone, Rede, GetNet, and Cielo.

B3, exchange infrastructure monopoly ($BOLSY, $B3SA3.SA)

Dominant infrastructure player: Brasil, Bolsa (exchange), Balcao (OTC), abbreviated B3, is the only listed exchange in the country where all listed stocks, debt, and futures are traded. It is also the largest custodian and central clearing party and the largest OTC market, plus a few other infrastructural functions (electronic lien registry, data vendor). This gives it a super dominant position, monopolistic in many areas, over the traded capital markets in Brazil.

The company results from a history of mergers between Brazil’s regional and vertical exchanges. In 2008, the Sao Paulo Exchange (BOVESPA) merged with the Mercantile Exchange (BM&F), joining listed stocks and debt with futures and creating the second-largest exchange in the world. In 2017, the company merged with Cetip, the largest depository, custodian, and clearing agency in the country.

Segments and drivers: B3’s revenues are well diversified among the different components of the capital markets, which provides a level of smoothing to the natural cyclicality of an emerging country stock market.

Listed equities and equity futures made up 35% of revenues in 2023. This segment naturally has a volatile component driven by average daily volumes (ADV) but also has more stable components like custody, listing fees. B3 has a monopoly in this segment.

Listed derivatives made about 25% of revenues in 2023. This segment is much more stable, as it stems from an operational need from companies to hedge interest rates, FX and commodity prices. B3 has a routing and cross-listing partnership with CME. B3 has a monopoly in this segment.

The two listed components made up 70% of the company’s operating income in 2023.

Data Services made up another 20% of revenues. This is also related to the listed markets, and is relatively monopolic, as the majority (12%) of the revenues were generated by access, meaning the software and fees brokerage houses need to operate on the exchange, plus co-hosting fees. Other revenues were composed of analytics-type data, and some custody elements.

OTC made about 15% of 2023 revenues. This segment facilitates trading of non listed debentures, bank funding, derivatives, etc. Its volumes are more related to operational needs from companies than the animal spirits, and by the monetization of the Brazilian economy. The company is not a monopoly but is dominant in this segment.

Infrastructure was only 5% of 2023 revenues. B3 runs a centralized registry of vehicle and real estate liens. This segment could have some potential into other asset classes, but is probably limited.

Leverage to Brazilian sentiment: Like most of the companies in this primer, B3 is still leveraged to the sentiment towards the Brazilian markets, via higher trading from higher valuations and more participation, to more financing activity, to a stronger BRL representing higher USD profits.

Operations, ownership and returns: Despite not having a majority owner (something strange for a Brazilian company), B3 is very well run. There are several indications of this:

The company’s operating margins have hovered around 60%, with drops to 50% (Brazilian bear market and depression 2016-2020), and peaks of 70% (low interest rates boom of 2020-21).

The company has nurtured products that have pushed growth in times of lower activity in the markets: mini-contracts in the index and interest rates (R$1.5 in new revenues), ETFs, BDRs, some tokenized assets, data analytics products, etc.

The company has returned R$26 billion to shareholders in the past five years, or 50% of its current market cap of ~R$55 billion. B3 does have capital requirements, mainly in the form of cash and securities (R$15 billion as of 3Q24). Most of these are financed via debt of R$13 billion, but still, the company has posted positive financial income for the past 10 years.

Valuation: B3 trades for a market cap of R$55 billion, compared to after-tax income of R$4.2 billion. This is a yield of ‘only’ 8%, but it is completely paid in the form of dividends and buybacks (returns have exceeded net income for every year since 2019) and is representative of what can be considered a low cyclical point for Brazilian markets.

Salient aspects

Mubadala, Abu Dhabi's sovereign wealth fund, has partnered with a Brazilian player to open a competing stock exchange in Rio de Janeiro in 2026, called ATG.

Like many Brazilian companies, B3 is involved in many tax lawsuits (according to some sources, tax litigation amounts to R$5.5 trillion or 75% of GDP). B3 could potentially be liable for R$15 billion in excess taxes, little of which has been provisioned already.

In addition, the company is liable for a claim involving the floating of the BRL in 1999, in which BM&F alerted the Central Bank of two banks holding short USD trades that were becoming systemically dangerous (the USD appreciated significantly after the BRL was floated), leading to a bailout of the banks. The claimants argue that BM&F was responsible for the losses carried out by the Central Bank. The decisions are at the Supreme Court, with a positive ruling in previous courts, but the claimants ask for as much as R$45 billion.

BTG Pactual: pure-play investment bank ($BPAC3.SA)

Note: Below, I am referencing the company’s adjusted revenue figures (which remove the effect of accounting as principal and present lending income in net figures).

Brazilian investment bank: BTG is one, if not the largest, investment bank in Brazil. It competes with the investment banking arms of the mega-banks. BTG is stronger as a prime broker and potentially as an investment bank, whereas banks are stronger in lending and asset management.

Segments, competition, and drivers:

Sales & Trading has consistently been around 40% of the company’s revenues, positioned as one of the main gateways to the Brazilian markets and an important market maker. In this area, the bank is the most solidified, as the large banks do not participate in market making activities as much. The segment is clearly driven by equity market sentiment.

Lending (net interest income) has been growing in importance, from about 10% to as much as 30% of revenues (also tripling the weight of loans on the balance sheet). This is a natural movement in a market where listings have been scarce since Brazil entered a prolonged bear market in 2012. It is a way to keep bank capital applied and maintain client relationships. I would not believe that BTG has an inherent advantage over the large banks in this area, especially considering that its portfolio is very small, about R$240 billion.

BTG also owns a stake in a small/mid-sized retail bank called Banco PAN (assets of R$41 billion).

Asset management has been shrinking for most of the past decade, from about 25% of revenues to 10%. The reason seems to be competition, probably driving management fees down across the board. In particular, as explained above, the open platform model allows bank customers to choose any type of fund. Equity markets also drive the segment, mostly because of performance fees.

Wealth management, on the other hand, has been growing significantly, taking the 10% share lost by AM. Here, principality plays a more important role. Whereas funds face commoditization, the more personal, trust-driven relationship of wealth management is harder to arbitrage. The segment seems more stable.

Investment banking proper has been very muted, at about 5/10% of revenues, except for some good years like 2020/21, with more listings. This is obviously driven by the period studied, as Brazil has been almost consistently in a bear market since 2012. Debt volumes are better, but the bank probably gets much less from these listings. Again, this is a segment where the bank is strong, but that requires equity sentiment to thrive.

Operations, ownership, and returns:

Like so many IBs, BTG Pactual still operates as a partnership. The partners own 70% of the company (30% by the group of about 10 largest partners). The partnership model is good for the alignment of interests but not so much for capital returns. Partners can sell their stake to the partnership and therefore do not need other sources of return. The company has grown its equity instead of returning capital, only returning the legal minimum (interest on equity).

The bank's cost structure naturally dampens operational leverage as bankers make variable compensation. During bad and moderate years, the company’s net margins (of net revenue) hover around 45%, reaching 55% during boom years. This is independent of significant year-to-year revenue volatility.

On the other hand, the company’s return on equity is a different movie, much more volatile, ranging from 13% to 25%, with an average of 21%. The driver of the better performance is good equity performance (listings for IB, performance fees for AM and WM). Equity has grown at a CAGR of 18% in BRL since 2011 and 8.3% in USD.

Valuation

BTG has a special listing structure, with three shares listed in Brazil. $BPAC3.SA is the common stock, $BPAC5.SA is the preferred stock of the bank, and $BPAC11.SA is a unit composed of one common stock and two preferreds. The preferred has no vote and priority during liquidation (no priority on dividends). I will refer to the common valuation.

BTG trades at a market cap of R$165 billion, 3x book, or a return of 7% on the equity, plus 8% CAGR on equity in the past 14 years, which have been relatively muted for the Brazilian markets.

XP: the Nu of investments ($XP)

Fintech revolution: XP did in retail investments what Nu and others did in traditional banking, a product revolution focused on mobile, simplicity, and low-cost service, targeted at the lower segments of a market. In the case of XP, this underserved segment was young, affluent retail investors who were too sophisticated for the low service provided by the mega-banks and smaller brokerage houses. Also, a segment getting a little skimmed by fees and clunky products.

The company won adepts by offering a simple, beautiful, functioning mobile product and introducing competitive innovations like zero-fee brokerage and an open investment fund platform (offering the product from competitors to their clients). This led to explosive growth, particularly during the low-rate cycles from 2018 to 2022 when clients and assets 5xed.

XP now has a decent asset base of over R$1 trillion (comparable to that of BTG above) or a market share of ~10/13%. It is much more dominant in retail, where it boasts a 50% market share in exchange-traded products (equities, futures, and secondary debt).

Maturity and competition via service expansion: The rate-hike cycle initiated in 2022 stalled the company’s main growth engine (revenues from investment services to retail have been flat since 2021).

This led the company to expand into other services like retail banking (credit cards, insurance products, collateralized credit), wealth management to its more affluent retail clients, and corporate and institutional investments (institutional trading, investment banking, wholesale credit).

This strategy has some advantages and disadvantages on each of the fronts:

Retail banking services: the company already owns a dominant position in the most affluent retail segment (people with savings invested), albeit only for investment services. The broker relationship requires more trust than the digital bank relationship, as the client has more assets under the custody of the broker than the bank. This gives XP an advantage over Nu or Inter.

On the other hand, providing banking services requires a big balance sheet, and XP does not collect deposits, meaning its harder to grow that balance sheet. Finally, the whole banking service segment is becoming commoditized, as I explained in the Brazilian Banking Primer, and more succinctly above, under Competition.

The opposite can also happen, with both mega and digital banks offering comparable investment services inside their ecosystems. XP already sells the broker-as-a-service software to Inter, for example.

Wealth management: I think XP has a really good position here because wealth management is a category that, in a certain sense, encompasses investment services. If XP already offers a better and cheaper product for people to construct their portfolio, it can also offer them good advice on how to structure that portfolio. Cross-selling insurance and pension funds is also easier.

The disadvantage here is that the company may not be able to make it work with a low-touch digital product, and more personal relationships may be needed. XP is already mixing digital tools (an investment advisor management software called Genius) with physical aspects (opening offices for advisors in the main Brazilian cities).Corporate banking: In this sector, XP suffers the same problem as in retail banking, i.e. a small balance sheet. It cannot be a big player in this arena, and building an efficient operation (good ROE and good efficiency ratio on a small balance sheet) may prove difficult.

Investment banking: XP’s best asset in this segment is the access to retail clients and funds to collocate. Still, I am also pessimistic here, as IB cannot leverage technology as much as personal relationships, building a structure, and having access to heavy-cannon capital (probably more abroad than in Brazil).

Institutional trading: Investment banks (say BTG) already serve this segment with detail and care. It is not the same situation as the ignored/skimmed affluent retail segment. XP will need to develop a tremendous product to win clients in this segment. It is also a more hands-on experience, not as digitalized.

In conclusion, I believe XP will face more competition from below (the banks trying to steal their retail clients), and expanding into retail, investment, or corporate banking will be hard. The best scenario is for XP to strengthen its dominance in retail investments by expanding its wealth management products.

Operations, control, and returns: The company is very well run, with EBIT margins ranging from around 25% to 30%. Even in the current challenging portion of the cycle, when the company needs to invest in new areas without the main cash cow growing (as retail investment services depend on equity market sentiment), XP has been able to leverage OpEx in relation to revenues and assets. It definitely has operating leverage potential in the case of a Brazilian bull market.

XP is controlled by its founders via a dual class structure, but the founders and Itaú still retain a 27% economic interest on the name, providing some alignment. XP has only recently started to return capital, at $150/200 million buybacks (net of SBC) per year, compared to $700/800 million in net income. The balance sheet is clearly growing.

Valuation: XP trades today at a P/E of 12x or a P/B of 2.5x versus an ROE of 21%. Considering the portion of the Brazilian equities market cycle, the company is still growing revenues at 15/20% (in BRL), and its margins are flat to up despite investment in new business areas, this does not seem overvalued.

Insurance: BB Seguridade ($BBSEY) and Caixa Seguridade ($CXSE3.SA)

Publicly trade bankassurance: The mega-banks dominate insurance distribution (known as the bankassurance channel). They already own client relationships and the upper hand by requiring at least some forms of credit life insurance on their own portfolios. The mega-banks market share ranges from 50% to 80% depending on the market, with health being the most competitive and auto, house, life, and credit life being less competitive.

BB and Caixa Seguridade are the only publicly traded bankassurance subsidiaries. The rest of the large banks (Bradesco, Santander, Itaú) did not list their insurance subsidiaries. The Brazilian stock exchange also has pure-play insurance providers, but they lack the distribution power of the mega-banks.

Partnership and exclusivity: BB and Caixa Seguridad operate under a partnership model, with JVs on each insurance vertical. The partners are well-known international players: MAPFRE for insurance, Principal Investment for pensions for BB, and CNP Assurances for Caixa).

BB and Caixa own most of the economic stake (generally 75%) but do not have control, which is given to the partner. The partner, therefore, manages the risk and economics of the businesses, and BB and Caixa record only JV equity income. They also only record net JV equity, reducing the reported size of their balance sheets.

BB and Caixa do maintain control of the distribution, which is charged against the JVs and makes up 50%+ of the whole operation's net operating income. This is done in exclusivity with the parent banks, giving these companies the significant competitive advantage of national coverage and a captive audience in some types of credit.

Shrinking industry: The operations of these insurance subsidiaries have to be read through the lens of an industry that shrank in relative terms. Insurance premiums grew in BRL for most of the past decade but slower than GDP and the BRLUSD depreciation. Why this happened at the same time as other sectors of the Brazilian capital markets rapidly developed needs to be clarified for me. The main explanation I can think of is insurance use grows with wealth per capita (you need to have something to protect) and that Brazilians use other systems for pension planning rather than insurance pension plans.

The result, however, was different for both companies. BB Seg was stagnant for most of the decade (dollar-denominated), while Caixa expanded its business more than 1.5x since 2015, albeit from a smaller start, and with an equity injection from its IPO in 2021.

Strong areas: BB Seg has a strong market share in pension plans (33% of the market, mostly from public employees), life (12%), credit life (20%), and rural insurance (lien protection, crop protection, 60% of the market). The company does not have a health insurance operation, and other areas (auto, home, mortgage) are relatively small. The position in rural (where BdoB is the absolute leader), public pension plans and credit life all stem from the exclusive relation with BdoB.

Caixa Seguridade, on the other hand, is strong where Caixa Federal is strong: mortgages, with 50% market share. The company is not as big in any other area, including home (15%), credit life (10%), or pensions (13%).

Somewhat bloated but impressive returns: Because the companies do not consolidate their JVs, their balance sheets and income statements are underrepresented, which elevates their returns. The EBIT margins are 90%+. Still, on the equity side, the difference is not meaningful (equity would be the same for a JV as for a consolidated subsidiary), and the returns are impressive. BBSeg generated ROEs above 50% and has net shareholder payout ratios above 80%. CaixaSeg’s returns are less impressive but still super high at 25/30%, with much lower payout ratios.

Valuation: Despite those tremendous equity returns, BBSeg trades at a P/B of 4.5x and a P/E of 7x versus the 12x average historically. This sounds very interesting, particularly considering the net shareholder payout ratio makes the yield quite real. Caixa, on the other hand, trades at a P/E of 12x, with a shorter trading history.

Payments: Pagseguro ($PAGS), Stone ($STNE), Cielo, Rede, and Getnet.

Card acquirers: The payment processors offer credit card acquisition and Point Of Sale (POS) devices. Their main business is to connect the merchant to the country's credit card and bank network to offer card payments to their clients. Some of these players are pure-play processors, like Pagseguro and Stone, while others are the arms of the larger banks, Cielo from BdoB and Bradesco, Rede from Itaú, and Getnet from Santander.

POS revolution: Back in the origins of the fintech revolution in Brazil (2015-2020), Pagseguro and Stone were among the first to offer very small POS and enroll the smallest merchants, allowing almost anyone to accept these types of payments. The payment processing arms of the large banks were focused on larger accounts but soon launched these devices, too, as they lost market share. Larger digital banks like Nu also offered POS.

Commoditization but high profits: This led to a process of commoditization of the technology known as the ‘Guerra das Maquininas’ (war of the POS). Today, the industry maintains certain concentration, with Cielo and Rede each holding about 20%, and Getnet another 15%. This would imply large banks still concentrate 55% of the market. Pagseguro and Stone each hold about 12%, with other players holding the remaining 20%.

Interestingly enough, the acquiring business remains highly profitable even today. Both Stone and Pagseguro post 30%+ EBIT margins, with Cielo posting similar figures before being delisted. The reason might be that the market was expanding a lot, as many MSMEs entered the space. However, it seems that the industry is growing more slowly at least since the start of the high interest rate cycle in 2022, which may lead to more competition and lower margins going forward.

Pure-play move to banking: Just like XP in investments, the pure-play payment processors are trying to grow by enlarging their service offerings and introducing other banking services. The most logical one is receivables discounting. In the case of Pagseguro, despite higher TPVs, revenue from payment processing has bene stagnant for almost two years, but the company keeps growing its financial income. Like XP, this strategic move's problem is the lack of a large balance sheet to sustain a large credit operation. People do not maintain their money on the payment processor accounts necessarily: Pagseguro processes around R$400 billion in TPV per year, and yet it only has R$4 billion in deposits.

Valuation is interesting: Only Pagseguro and Stone are separately traded (with Cielo delisted this year), with both stocks in the doldrums. Pagseguro trades at 2x EBITDA, and Cielo at 3x. Great examples of growing into a valuation as these names started at 100x EBITDA in 2021. Although the names have clear challenges in competition (revenue/TPV is going down as acquiring gets more and more competitive), the potentiality is there for a cyclical comeback in a more expansionary period of the Brazilian economy.

References

Brazil Central Bank

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in the Blog are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual or on any specific security or investment product.

Amazing write up, thank you 🫡