A Short Primer on Investing in Brazilian Stocks

A concise Brazilian macroeconomy framework, ways to invest, and analysis of the main sectors listed in ADRs

During the commodity bull market of the 2000s, Brazil’s EWZ generated a return of 19x in six years. However, as commodities entered a prolonged bear market, the economy entered a lost decade, and Brazil’s developed economy dreams were shattered. The EWZ is still 50% down from its 2008 peak.

But now, fueled by the bull market in commodities and geopolitical conflict, Brazil might be awakening from a prolonged sleep. Even the mythical Lula (who ran the last bull market from beginning to end) is back in the presidency.

This article reviews the basics of investing in Brazilian stocks. This includes a simple framework for understanding the Brazilian economy, the different ways to invest in Brazilian equities, and a review of the largest sectors accessible via ADRs.

Are we at the gates of another Brazilian bull market? That depends on the health of the commodity markets and is not something I’m trying to answer here. However, many Brazilian companies are generating great structural returns today, even without a bull market, and I’ll explain why.

As always, if you liked this post, please share it with friends or colleagues!

Investment guardrails for Brazil’s macroeconomy

Brazil is generally thrown in the ‘emerging markets’ bucket, meaning something like ‘backward but with the potential to become developed.’ I don’t think this definition really helps, and it can lead to misconceptions like too much reliance on Brazil catching up to developed economies.

It is difficult to explain a country with a few concepts, but it is much more difficult if those concepts are incorrect. Here we will review some border conditions that are well established in the data. Understanding the country’s cyclicality, lack of long-term growth, and cost-of-capital structure will help you evaluate Brazilian companies.

1- Brazil is a proxy investment in the commodity cycle.

Brazil has been heavily influenced by the commodity cycle in the past two decades. The chart below shows Brazil’s GDP per capita (blue area) versus oil prices (purple line). The correlation is clear: the Brazilian economy expanded between the early 2000s and 2012/13, in line with increasing oil prices. When oil prices started to fall, the Brazilian economy flopped and has not recovered since. The Brazilian EWZ ETF (orange line) has an even clearer correlation with the oil price, indicating that this is also how markets have evaluated Brazil so far. I use oil as a proxy of commodities because oil is an important input in many commodities, especially in agriculture, and captures the main drivers of commodity price dynamics, like global growth and geopolitical tension.

Why is the correlation so strong? I believe there are two reasons. First and most obvious, most of Brazil’s exports are raw materials: metals, oil, crops, and meat make up about 75% of the country’s exports. Second, and much more important, natural resource rent averaged 4% of GDP for the past 20 years, with peaks of 6/8% during commodity booms. If we consider that corporate profits make up about 10/15% of GDP, this means that between a third and a half of all profit is generated by natural resources. Natural resources are a big component of the economy and a bigger component of economic surplus. Finally, Petrobras, the country’s public-private integrated O&G conglomerate, makes up almost 15% of the country’s public market cap.

2- Brazil is a rentist economy with low competition, low potential growth, and big profitable moats.

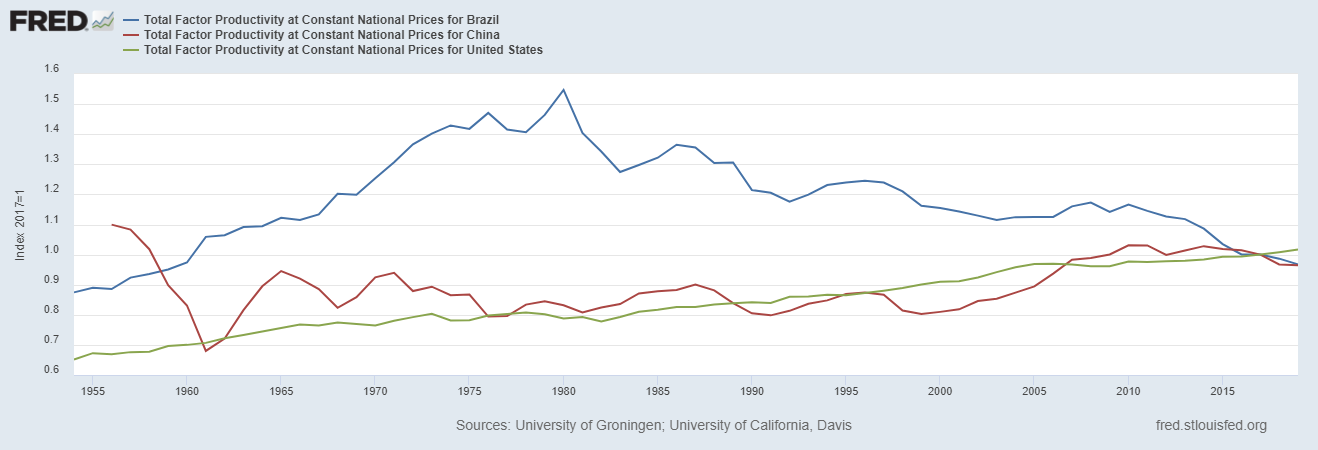

Basic growth theory says a country can grow via capital, labor, or productivity. In the long term, only productivity matters, as labor and capital post diminishing marginal returns. So far, Brazil has fared very badly in terms of productivity. In fact, the economy's productivity has been a negative factor in GDP growth for the past four decades. This does not bode well for long-term growth prospects.

There are a few reasons to explain this. First, Brazil is one of the most closed economies in the world, with low trade-to-GDP ratios and the second-highest position in non-tariff barriers to trade. Second, the country invests very little in capital and infrastructure, especially for a large country. For the past four decades, Brazilian gross investment has been below depreciation in several areas, including infrastructure. The same can be said of investment in education, particularly in young children. Other factors involve a large and inefficient dirigist state, difficulty in doing business (red tape), and regulatory capture.

This indicates that there is no evidence to support an investment thesis based on Brazil catching up to the developed economies. This is a negative factor when considering the long-term potential of Brazilian companies.

However, as investors, we actually like low-competition markets because they increase returns on capital. One example is the apparel industry, where Lojas Renner (the Brazilian Zara) has posted a 20% average ROCE thanks to tariffs on foreign apparel products. Large global chains (Zara, H&M, Forever21, and soon Shein, probably) have not been successful in Brazil. Another example is the banking sector, where the average ROE has been significantly higher than in the US for over 20 years. Another positive aspect of low integration into global supply chains is that Brazil has much less to lose from those chains as the world deglobalizes.

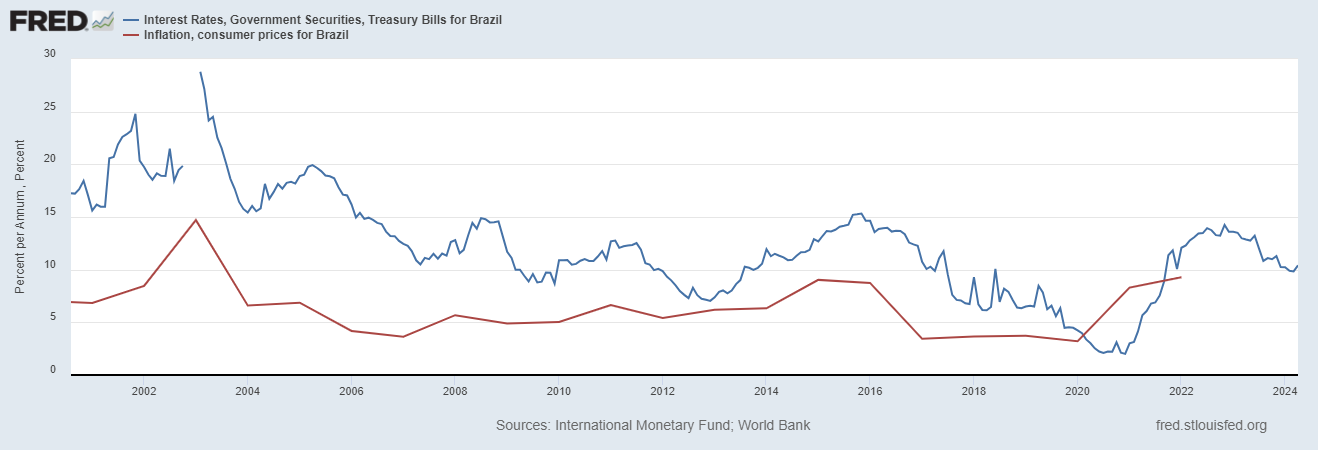

3- In Brazil, the cost of capital is real, and it shows up in valuations and dividends

Brazil has posted very positive real interest rates on its currency, ranging between 3 and 6% on government bills, even during the recessionary decade of 2013-2023. Only shortly during the pandemic did the Brazilian policy rate fall below inflation.

In the developed world, the need for yield from liability-driven institutions drove capital to the equity markets, but this did not happen in Brazil. Brazilian pension funds or individuals don’t need to engage in risky equities when they can get a positive real rate of return by lending to the government. This shows up in companies' costs of capital, particularly in the cost of equity.

This affects investors in a few ways:

Brazilian valuation ratios are lower than in the US or the developed world (conversely, yields are higher). Any investment thesis based on a peer valuation where peers are in other countries is probably incorrect. There is no reason why Brazilian equities should ‘converge’ to OECD or emerging market valuations.

Brazilian equities tend to show high dividend payout ratios. In fact, Brazil mandates that 25% of net income be distributed to shareholders every year.

Brazilians managers are much more respectful of capital. This shows up everywhere: companies hold long 5 to 10 hour investor days, going over a lot of operational details; growth companies quickly try to reach profitability or IPO only after they are profitable; and analysts are much more inquisitive in their discussions with management.

Investing in Brazilian stocks as a foreigner

As a foreigner, there are three broadly accessible ways to invest in Brazilian stocks: ADRs, ETFs, and locally. Investment banks probably offer alternatives like return swaps, too.

There are 76 ADRs or US-listed Brazilian companies covering most of the economy's sectors; we will review them later. About half of them are small caps. The problem with ADRs is that, in many cases, they are not sponsored, and their volume is super low (the notional volume of all Brazilian ADRs is about $1.5 billion versus a total market cap of about $800 billion, according to Koyfin).

A second possibility is to invest via ETFs. Unfortunately, there are only three relatively liquid, unlevered alternatives:

EWZ, based on MSCI Brazil 25/50, is the largest by far. It covers large and mid-cap stocks and has 49 constituents. Energy, financials, materials, and utilities account for 75% of the index.

FLBR, based on FTSE Brazil RIC Capped. Very similar to EWZ but with a much lower AUM.

EWZS, based on MSCI Brazil Small Cap. Also very small in terms of AUM.

The third possibility is to trade directly in Brazil. The B3 exchange has more than 400 companies listed. The problem is that Brazil requires foreigners to register with its Securities Commission and the Central Bank. The process can be simplified via a foreign broker, and some Brazilian investment banks offer non-resident investment services, such as facilitating those registrations. I have not asked for the costs of such services. Some US brokers, like IBKR, offer trading on Brazilian CFDs.

Finally, foreign investors receive equal treatment in their shareholdings as local investors. Brazil does not tax capital gains or dividends unless the foreign investor is domiciled in a tax haven (an opaque jurisdiction or a jurisdiction with less than 20% income taxes). There is an exception, though: Brazilian companies can treat their dividends as interests on equity, deductible from corporate taxes, but taxed at the investor level as regular income. Therefore, dividend tax treatment for the investor depends on how the company elects to treat those dividends.

An overview of Brazilian sectors represented in ADRs

As mentioned, 76 Brazilian companies are directly listed in the US or have sponsored or unsponsored ADRs. About half of them have less than $2 billion in market cap. Here is a review of the largest sectors, concentrating on financials and commodities.

Banks represent only 8 companies but occupy 5 of the 10 largest positions by market cap. The Brazilian banking sector is famous for having one of the highest industry-level ROE worldwide. I will publish a specialized article on these companies by the end of June.

A subsegment of banks is payment services like Pagseguro and Cielo (separate from neobanks like Nubank or Inter). Brazil is very advanced in its currency digitalization efforts.

Commodities are obviously another big chunk of the market. Commodities companies (particularly in O&G and mining, trade at EV/EBIT ratios below 5x). I have covered the meatpackers and agricultural companies in a previous article.

Oil & Gas is basically Petrobras, the public-private integrated company that makes up 1/8 of the Brazilian stock market cap. Petrobras dominates this market because of a half-century monopoly on O&G, which is only moderately liberated today. Ultrapar, Vibra and Cosan also have a stake in refining and downstream segment, which has been more liberalized.

Mining and metals comprises Vale (the world's largest iron and nickel producer), three steel producers (Gerdau, CSN, and Usiminas), and several junior miners, with a focus on rock lithium.

Meatpacking is another large and dominant industry, with giants like JBS and Marfrig and smaller players like Minerva. These companies oligopolize the Brazilian meat market and have dominant positions abroad.

Agriculture companies are a small group in the stock market of only two companies (Brasilagro and SLC Agricola) despite playing a vital role in Brazil’s economy. Adecoagro is not considered a Brazilian company but mostly operates in Brazil. Suzano is a leader in eucalyptus forestry and paper.

Utilities make up one of the biggest sectors, probably related to Brazilians’ yield demand.

Consumer-centered industries are relatively less important. We can mention the beer giant Ambev, but outside of it, the next consumer-based company in the market cap ranking is at position 20 (Raia Pharmacies). Mercado Libre, the LatAm e-commerce leader, is not listed in Brazil but derives a good chunk of profits from the country. Despite this, I think consumer companies have the most potential for high returns, given that these companies (along with banks) can ‘hunt in the zoo,’ meaning the enclosed, low-competition Brazilian economy.

Education is a particularly interesting subsegment of consumer industries, with four Brazilian companies listed in the US and more participating indirectly. Education is a sector with high potential for building a brand and pricing power, positive competitive dynamics, and friendly regulation.

Conclusions

Brazil is grouped into just one more emerging market. The bulls think it’s the next China, and the bears think it's corrupted to the bone and fundamentally anti-capitalist. I don’t agree with any of these views. Rather, I consider Brazil to be a capitalist but strongly closed country.

The combination of a closed, low-competition economy with positive real interest rates has created an equity market that returns capital handsomely (although it cannot grow invested capital too much). I believe this is particularly true of sectors unrelated to commodities. Almost half of the ADRs have ROEs above 15%.

I plan to analyze some of these sectors in future primers and deep dives, including banks (to be published in late June). If you want to receive that analysis for free, don’t forget to subscribe.

And, as always, if you liked this, share it; it will help me a lot!

Disclaimer: No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. The author is not licensed by any regulatory body to provide financial advice. This article is posted for educational and enterntainment purposes only. No information is warranted by the author as to completeness or accuracy, expressed or implied, and the author assumes no obligation to update or revise such information if the information becomes inaccurate or obsolete. Certain information may be based on third party sources and, although believed to be reliable at the time of publication, has not been independently verified and the author is not responsible for third-party errors.