Focus is essential for long-term investing. Time, mind, and money, the treasures of the investor, are scarce and should be allocated only to the best candidate companies and ventures.

Furthermore, a lack of focus is dangerous. Without a prioritization framework, the investor is overwhelmed by information and becomes anxious. Contrary to Buffett’s baseball analogy, the investor tries to swing at every ball. This leads to biases. Some of these are:

Sunken costs: believing that the time spent on a name ‘has to be worth something’ and, therefore, being more prone to start a position.

Overconfidence: believing the information collected is relevant and sufficient for the investment decision.

Flawed heuristics: using quick fixes to arrive at a decision, like excessive use of earnings multiples.

Framing and anchoring: using only incongruent pieces of data, especially the ones made readily available by management in filings and presentations.

In the spirit of prioritization and focus, I have developed a series of criteria that inform the stop-go decision when first reviewing a company. These allow me to discard low-potential companies quickly.

I review these criteria before reading almost anything else about the company. I don’t care if it has a cure for cancer; if it cannot pass these criteria, it is a no-go for me. In fact, if it cannot pass these criteria, I prefer not to learn about the company to avoid letting the biases in.

I will make biased mistakes when rejecting companies quickly. However, these omission mistakes are less dangerous for my wealth and professional future than commission mistakes. No one lost real money avoiding an investment.

The first rule of an investment is never lose money (Buffett)

It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent (Munger)

These criteria are more relevant for small caps (also nano and micro caps), innovative companies (R&D heavy, new products), and young companies. They might not work as a valuable first filter for midcap or more traditional, older companies.

The equity account cannot lie.

The statement of changes in equity records an abbreviated history of the company. It is also an indelible record that cannot be changed via writedowns and restatements.

The statement tells you exactly how much money the shareholders have invested into the business and how much of that capital remains today.

The statement will generally show a loss for young companies in new markets or ventures: capital has been spent on R&D, D&A, SG&A, etc. Profits are still inexistent or not enough to replenish the equity account.

We must compare that invested (or lost) capital with the company's achievements to answer the fundamental question in investing: how prudently and fruitfully is capital allocated by this management team?

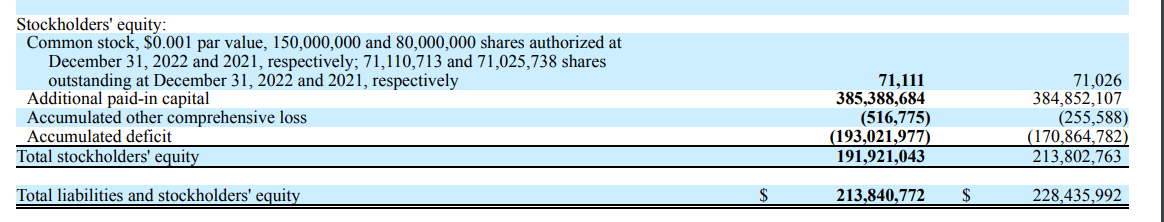

Let’s use AquaBounty Technologies (NasdaqCM:AQB) as an example. The equity account in the balance sheet shows equity contributions of $386 million, of which $193 million have been used.

Thinking as a capital allocator: what would you accomplish if you were granted $193 million to manage a business or venture? What if you put that into an index fund? What if you gave that money to a business genius? That is the opportunity cost of those $193 million, so we hopefully have something good in exchange.

Achievements 1: Profitability and sales

First, we want to check if the company generates revenues, how much, how fast it has grown in the past five years, and whether or not it is profitable in any sense (gross, EBITDA, operating, net).

Profitability is paramount because it signals that management is aligned with protecting capital and the company is passing some form of market test. Without profitability, revenue is the next simplest gauge of market acceptance.

Again, we prioritize simplicity because we want to save time at the expense of some mistakes. Revenues and profitability are pretty objective and universal measures for market success.

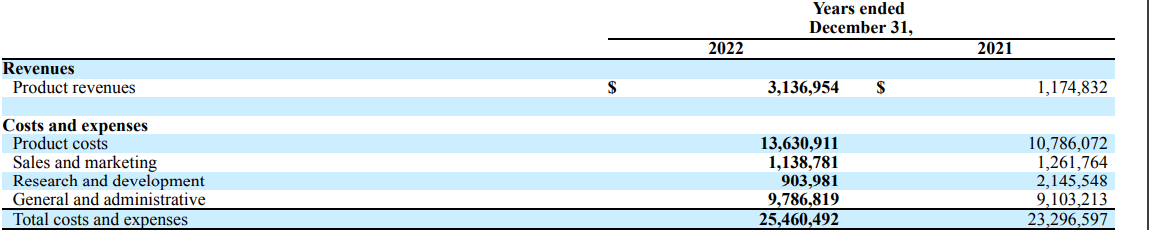

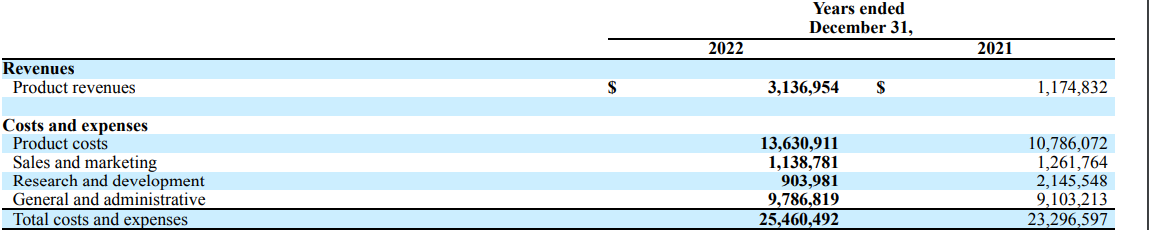

In the case of AQB, in exchange for $193 million, we have a business that can generate $3 million in revenues at a gross loss of $10.5 million, which is not great.

Achievement 2: Innovation by management proxy

However, the business is growing fast and may be on the brink of a breakthrough and breakneck growth (or so every management says every time).

The company might be investing in areas that cannot be capitalized and, therefore, show up as losses, such as educational marketing and sales efforts, research and development, or process improvements. This is especially true for companies creating a market. It might be a new app, a new method of producing bioethanol, or, in the case of AQB, a new breed of indoors-raised salmon.

We do not want to get into the weeds of the new product and its market because we want to avoid losing time and letting biases get in. Further, innovation is complex and only bears fruit after a long series of well-made decisions. Outsiders can't evaluate all those small decisions and their soundness. They have to trust management’s criteria. I would argue that the company’s management is more important than the product under development at this stage.

Managerial compensation as a percentage of total costs

Therefore, my next step is to evaluate management and its alignment with the shareholders. One quick way to check management alignment is to compare G&A expenses or management compensation to total costs. G&A should be the smallest expense component.

If we finance an R&D company, most money should go to R&D expenses: researchers, labs, tests, and prototypes. If we invest in a commercialization effort, most money should go to sales and marketing or costs of goods sold. If the managers get most of the money, we are the patsies.

Why would I want to pay a management team $3 million yearly to have them command over $5 million in R&D expenses? That’s simply inefficient. It implies terrible alignment and that the company serves its managers, not its shareholders.

One variation of this test is management cost over CAPEX. If the company is doing massive physical investments, these will not appear as expenses (initially) but will require G&A and managerial resources.

In the case of AQB, G&A is 50% of costs, and some managerial compensation was probably baked into product costs as well. That is not good. The company did a lot of CAPEX in FY22, $67.5 million, but only $6 million in FY21, when G&A expenses were the same.

Management’s previous companies

Being a stock promoter or crooked manager is immoral but probably profitable and fun. After sucking the blood out of a company, bad managers tend to move to another one.

Most companies publish a small bio excerpt on their managers, executive directors, and Chairman. If they have served previously at public companies, you can check how the companies did.

If the company's CEO was previously the CEO of another company whose stock went from $10 to $0.02 today and is trading OTC, you should probably not give him money.

Short history lookback

Many times, even good management teams fail.

If the market does not accept the product under development, honest managers would wound up the company and return the remaining capital to shareholders. On the contrary, self-serving managers will pivot to the next shiny object to raise money again and continue burning equity.

A quick way to check this is to read the first two or three paragraphs of the business section of random annual reports. If the company’s business has changed many times, management is just trying stuff at the expense of shareholders.

One exception to this is a complete pivot of business, management, and assets. This sometimes happens when a private company makes a reverse acquisition of a waning public company to have its shares listed. In this case, one should revisit the equity losses step to only account for the losses generated since the new company was acquired.

Sum up

I do not want to spend any time reviewing bad companies. Unfortunately, the nano-cap, micro-cap, and small-cap spaces are full of them.

By running these quick checks, I can have a good grasp of whether or not a company is worth any research at all in less than 20 minutes:

How much capital has been consumed in the business? Check the statement of changes in equity.

Has the company generated revenue and profitability with that capital? Check the past two income statements.

How much is management and the administrative structure getting out of the company? Compare managerial compensation and G&A to total expenses and CAPEX.

Does management have a previous record of bad behavior? Check their previous companies.

Does management change the business plan every few years? Check previous annual reports.

When a company passes this test, I can spend more time reviewing whether or not its operations, strategy, and market positioning make sense and are worth a deep dive. That will be the content of (potentially many) other posts in the future.

Keep in touch!